POSTS

Am I normal? An intro to mental health in the doctorate

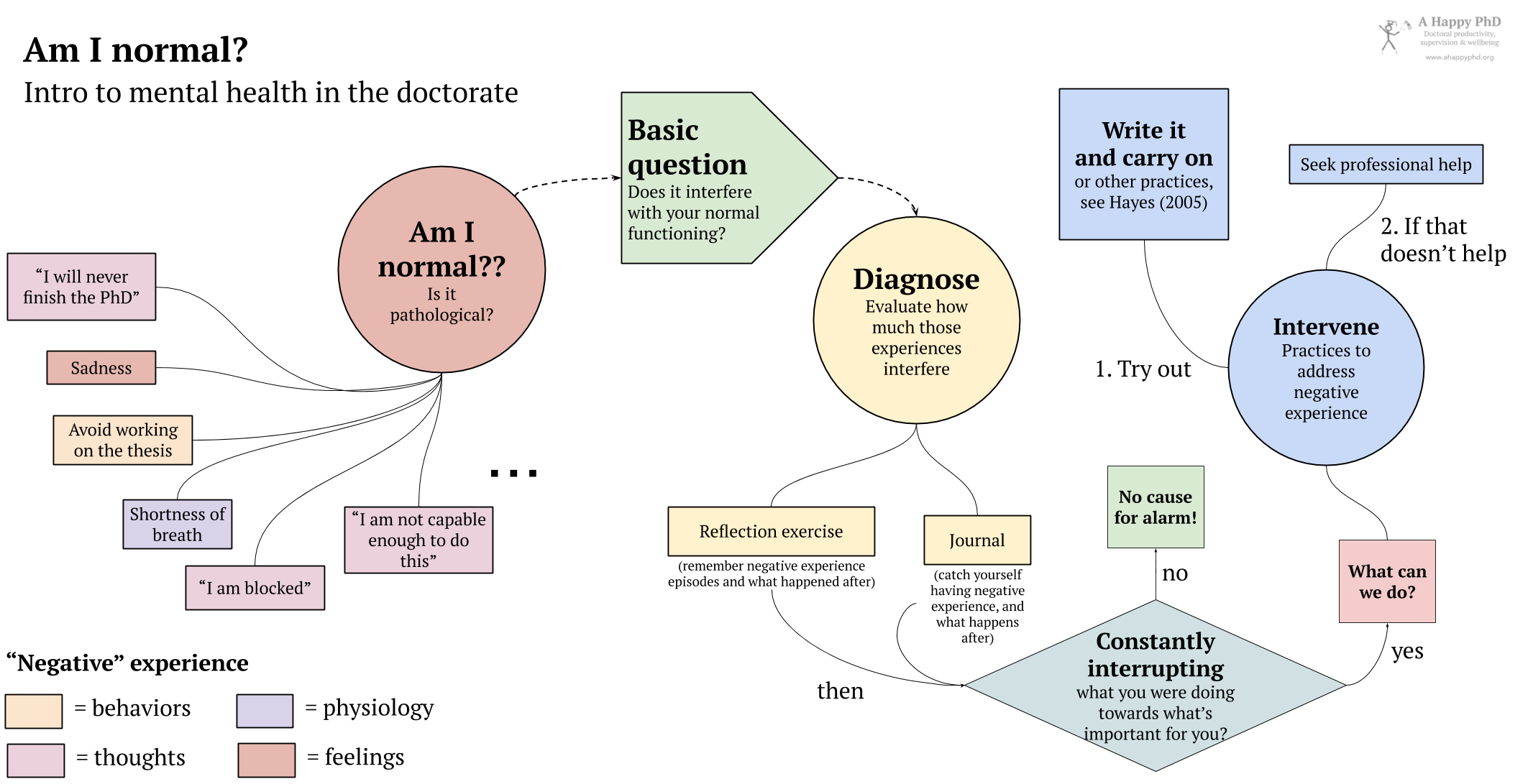

by Paula Odriozola-Gonzalez, Luis P. Prieto, - 9 minutes read - 1874 wordsBy now, we have established that PhD students (and academics in general) seem to be at a higher risk to develop mental health problems like depression or chronic stress. But, how can we know if we have one of these mental health problems, right here, right now? In this post, co-authored with colleague, friend and therapist Paula Odriozola-González, we go over a few basic concepts of psychopathology, and propose criteria and simple practices to help separate internal experiences that we all go through at one time or another, from the more serious stuff.

Take a look at this list of thoughts and ideas:

- I’m never going to finish

- Why does it seem that everyone progresses faster than I do?

- I’m always tired

- I’m not in the mood for anything

- Don’t know what I’m doing with my life

- In the end, why am I doing this?

- I feel like my life does not go forward

- Sometimes I’m short of breath

- I have trouble sleeping

- I don’t know what to do next

- I’m not capable enough to do this

- I’m in over my head with this PhD/research thing

- I’m blocked

Since you started the PhD, have you ever had any of these thoughts? Count how many different ones you’ve experienced so far.

If you are like any of the PhD students that came to our workshops on progress in the PhD, you’ve experienced at least one of those. Indeed, more than half of our students had experienced 3 or more. I can certainly tell you that many of those thoughts passed through my own mind (some quite persistently) during my own PhD. Especially in the tough times, when things didn’t go the way I wanted. And I didn’t even have a difficult PhD process.

On top of those thoughts, there are other worrisome symptoms that we might experience, be them physiological (e.g., elevated heart rate in the absence of exercise, trembling), emotional (e.g., a feeling of sadness) or behavioral (e.g., avoiding work related to our thesis)1. Yet, negative thoughts like the ones above are very commonly found, and hard to separate ourselves from.

And, on top of that, during the current times of coronavirus, an additional set of negative thoughts, feelings and body sensations has been added to our internal experience: having trouble sleeping, feeling a pressure in the chest, thinking “my relative is going to die”, “the economy is never going to recover”, “people are going crazy (or stupid)”, “we are all going to die”…

Does that mean that we are all pathologically anxious or depressed? That we are all crazy people?

The basic answer to those questions is “probably not”. Such experiences, such thoughts and bodily sensations are just an integral part of what it is to be a human being. Sometimes we get positive experiences like joy or creative ideas… and sometimes we get other experiences, like the ones above, which we label as negative.

Then, you might say, when should we start considering that we have a problem?

The basic answer is simple, yet more subtle: whenever these symptoms start interfering with our normal functioning2. In other words, when these symptoms make us suffer, and we start to consistently change the way we act, the way we live, to avoid having them. In a way, these “negative experiences” become the center of our lives. This is what some psychologists call experiential avoidance, and is one of the common denominators of mental health troubles, from anxiety and depression to chronic pain3.

I have plenty of examples of this avoidance, from my own PhD: that time I started working more on collaborations with other researchers than in analyzing my own data (to avoid the uncertainty of whether results would be good – or the certainty that they were not good enough); or that other time I spent weeks reading more and more literature (which I knew I could do effectively) rather than drafting the plan for my last year of dissertation (which would kickstart a long period of hard, intense work which scared me)… Luckily, in my case these avoidance strategies did not go on indefinitely: either I shook them off myself, or others helped me do it by pointing them out and encouraging me.

Probably you have your own go-to avoidance strategies too. We all do. For some of us it can be distractions like binge-watching Netflix, continuously playing computer games, or reading about our “passion topics” not related to the thesis. It can be about numbing out these difficult emotions with alcohol or drugs. It depends on the circumstances and on the person.

And, let’s be clear: there is nothing wrong with any of those avoidance strategies per se, if done sporadically. However, when it becomes a repetitive, almost compulsive thing we consistently do to avoid those negative experiences, it can be a problem. When it interferes with our normal lives and what we consider important in them (e.g., to become doctors, our role as a parent, a son, a friend, a professional… whatever is important for us specifically), we may be heading for trouble.

Thus, if you feel you are able to work, to function and act normally towards your goals, towards the important areas of your life, probably you are fine. Note that I wrote “normally”, not “optimally” or anything like that: sometimes these negative experiences visit us, and sometimes we allow them to be there for a while, or we allow our avoidance strategy to happen. And that’s OK. However, if these negative thoughts or feelings (or avoiding them) seem to be playing too much of an important role in your life, it may be worth investigating. How? Other than going to see a professional therapist, you can try a couple of simple things, following the same schema that we followed in the happiness in the lab series, of first diagnosing (observing how things are currently for us), and then intervening (i.e., trying some new practice or changing what we do):

- Observe/Diagnose: Try to remember the last times when these negative experiences (thoughts, feelings, actions) happened to you. What were you doing? How was the situation, who was there with you? And what did you do as a response? Better yet, you can spend some days carrying pen and paper (or a journal) with you, and noting down these episodes as they happen: what was the situation (what were you doing, where and with whom), what negative or problematic experience arose, and how did you respond. After several days of doing this (or remembering 6-10 of these episodes), try to see if there are trends in these episodes: common feelings or thoughts, common places or people or activities that prompt them. And, especially, what is your response to these problematic experiences: if, after thinking “I’m never going to finish the thesis”, you are able to keep doing what you were doing (even if the thought remains there for some time), then probably you are functioning according to your values and goals (i.e., there is no cause for alarm). If you find yourself constantly interrupting what you do, if those thoughts or feelings (and what you do to avoid them) are becoming an obstacle to doing what you think is important (e.g., complete your thesis), maybe you can try the simple practice in #2 below…

- Intervene: Keep some pieces of paper and a pen with you at all times. Then, throughout your day, try catching yourself when you are thinking these thoughts or having these feelings (e.g., “I’m never finishing this thesis”). Be simple about it, don’t judge yourself or the thought. Simply notice “ah, I am having this thought of never finishing the thesis”, as if it was something interesting you just discovered (it actually is!). Write the thought on a piece of paper (yes, write “I’m never finishing this thesis” on the paper). Notice how, as you put it on paper and are able to look at it there, in front of you, its power over you is somehow limited. You don’t need to reject it or destroy it (this is not voodoo magic), but you can just fold it and put it in your back pocket, and continue what you were doing. The thought may or may not disappear, but even if it accompanies you, you’ll have shown it (and yourself) that it can be there and you can still function as a human being that goes towards the goals you consider important4.

We hope those tips prove useful to you. This kind of techniques are used by a particular approach to psychological therapy called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which is part of what is called contextual therapies5. The “contextual” bit is important, actually: it means that these concepts and techniques are not blanket recipes that will work always for everyone – rather, the should be understood and applied in our own particular context (e.g., the same behavior of going out for a run can be an important nourishing action for someone, and a problematic avoidance strategy for another person). In the next post, we’ll introduce some more basic concepts and practices related to this approach, which could be useful to deal with these negative experiences during the doctorate; and especially, the notion of acceptance (which already featured in the post on factors that seem protective against depression in the PhD).

Bonus: How are you doing during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Just a few more words to check in with all of you and ask how things are going, given the current special circumstances during the COVID-19 emergency. I’ve talked recently with quite a few PhD students, and the variety of experiences is staggering: some have more time to concentrate now, and seem to be advancing faster; for others, the current lockdown has brought all plans and advance on their thesis to a grinding halt. If you, like me, are curious to know how our small community is doing during this crisis, please answer the few short questions below. It should take less than a minute. And you will get to see the survey results once you respond.

Header image by fbiwu

-

You can find a more complete list of common symptoms associated with mental health problems in the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales, see Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. Official website. ↩︎

-

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5 ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing ↩︎

-

See, e.g., Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(6), 1152. ↩︎

-

These and other practices can be found in self-help guides like Hayes, S. C. (2005). Get out of your mind and into your life: The new acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications. ↩︎

-

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665. ↩︎

Paula Odriozola-González

Paula is an Associate Professor at the Universidad de Cantabria (Spain). As a psychologist and licensed psychotherapist, she is very interested in supporting the emotional well-being of university students and how it relates to their academic performance.

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.