POSTS

Making important decisions about the doctorate (II)

by Luis P. Prieto, - 10 minutes read - 1999 wordsWhat can we do, when we have to take a hard decision about the PhD (like changing supervisors or leaving doctoral studies altogether) but we don’t really know which way to go? In the continuation to last week’s post, we see how to go about the actual decision-making, to choose the option that has the best chances to satisfy us in the long run.

OK, quick recap from last week: we are facing a difficult situation in our PhD, and don’t know what to do, or it seems we have to choose between two undesirable options. In the first phase of my proposed decision process, we expanded our understanding of the situation and the available options: We reflected on our own values and purpose (what is important in life for us); we applied these values/purpose to the PhD itself, to understand what aspects of it we value most (and which are secondary); we found out and talked with other actors in the situation, to understand their motives; we brainstormed more alternatives, to unstuck ourselves from having only easily-available but not-that-desirable options; we used our institution’s resources and information to get further help; and we talked with some more people about the situation, to get alternative perspectives and new ideas about potential paths of action.

Analyze the options and take a decision

By now, we will have in front of us, not one or two, but actually many different alternatives, options and (pieces of) potential solutions to our dilemma. At this point, we may be tempted to throw away most of them, and remain with the initial, obvious 1-2 options that we started with, because the others are just… unconventional. Resist that urge. Maybe delete those that are clearly impossible, but leave yourself at least a good handful of options that could, maybe, work. Now, its time for phase 2 of the process: analyze the options and take a decision. As in phase 1, here there is also a small piece of meta-advice about how to go about this. The key for good decision making, according to psychologists and other researchers of the topic, is to slow down, if you can: making decisions on a hurry has all sorts of effects, and many of those effects are not positive1. Here is a list of things we can do to improve the actual taking of a decision:

- Try some “analytic intuition”. Despite all the steps that we took in phase 1 to expand our understanding of the situation, chances are that we’ll have to take a decision under incomplete information. In these situations, we often go with our “gut feeling”, our intuition. In this interview2, Daniel Kahneman (Nobel in Economics and one of the most influential psychologists alive), shares a critical trick when dealing with decisions that are complex and uncertain, learned from his research in decision-making: “Delay your intuition. Don’t try to form an intuition quickly. Focus on the separate points, and when you have the full profile, then you can have an intuition.” So, basically, we need to select different criteria or dimensions against which we’ll judge each option: what are the economic consequences of taking this one option? how will it impact our family? and our autonomy? our friendships? is it aligned with our purpose in life? with what we value about the PhD? Make a list of all these important aspects, paying special attention to put there questions that represent our personal values and the main thing we value about doing a PhD (as per last week’s post). Now, let’s rate each option from 1–10 on each of these different aspects or kinds of consequences. Only after we have done this review dimension by dimension, we can allow ourselves to make the intuitive, but informed, decision. We could also just take the option with the highest average score, but that is not mandatory, since some dimensions could weigh more than others in our hearts and minds.

- Prototype the most likely options or decisions. One of the biggest problems with decision-making, especially in decisions that will affect our lives deeply, is that we humans are notoriously bad at predicting what will make us happy (or unhappy), and how we will feel once we are in a certain situation (like “researching topic X in lab Y”)3. By now, after doing all of the above, we will probably have 1-3 options that are clearer favorites. We could just take the decision right now by flipping a coin but, if we still have the time (remember the motto, “slow down”!), we could also try a “prototype”, a smaller version of our favorite options4: the idea is to try to live for a short time, or at least vividly imagine, how our lives would be under that option. How do we prototype a new direction in life? Here are two ideas, but others are also possible:

- Talk with people that already do what you are considering. Chances are, there is somebody out there that is already doing a PhD in that lab, or working with the methods or topic you are considering. The idea here is to get in touch with them and see if they can spare a short while for a conversation, and have them describe how it is to live under that option/alternative: what they spend their time really doing, what are the main advantages, or pain points. We need to picture in our minds how it is to live that way. Do not emphasize so much whether they are happy or not (which is a judgement they’ll do according to their values, not ours), but try to understand why. It is important to note that this is not a job interview, so don’t expect a job offer from them – just some friendly conversation about how it is to live/work/research in that situation we are considering.

- Live a smaller-scale version of the option: if we are considering a particular lab to do our PhD, we can propose to do a summer internship in that same lab; if we are considering a two-year postdoc, we can do a one-month research stay to start collaborating with them; we can do a small pilot study in the direction or methodology that we are considering for the big change in thesis direction… It may turn out that we actually like the new topic that we feared, or that it is hell to work in that very prestigious and cutting-edge lab we were aiming for.

- Visualization: Give advice to your best friend. Now, we really have all the elements we need for the decision: options, and in-depth analysis, even actual experience with some them. Yet, even with all that in our hands, we may feel “analysis paralysis”, or we may just be overwhelmed by the importance of the decision, unable to choose. In these situations the following visualization exercise may help put ourselves in the right frame of mind and unblock. Take some minutes alone in a quiet place, close your eyes and imagine that you are sitting with your best friend; they come to you in distress, saying that they have to make an important decision, and that they have all this information (the one we have gathered till now), but still they cannot decide; they ask for your advice: what to do? Do not rush an answer. The idea is to, really, visualize our friend and reason (in writing, if that helps you) what would be our advice to them and why.

- If you still resist the decision: Set your fears. Now we have a decision (whatever we would advice our best friend). We know this probably is the right option for us. Still, sometimes we look at this option we know is right, and still we cannot bring ourselves to do it. It is too scary, or it sounds just too unusual. It happened to me when I decided to leave a well-paid, stable job in industry to start an academic PhD with no funding. Once I decided it was what I wanted, it still took me a while (and a lot of willpower) to start acting upon that decision. When we are sure that one option is the right one for us, but still fear taking that path, we can take millenia-old advice from Stoic philosophers, and do what they called a premeditatio malorum (also called “negative visualization”): basically, you take some time to really reflect upon the question “what’s the worst that could happen (if you do the thing you are afraid of doing)?”. And I mean really thinking it through and writing down things like: what bad consequences can come from doing it (and how likely they are), how to avoid these bad consequences, or recover from them if they happen, what bad consequences (especially, in the long-term) can come from not doing what we fear doing, or what long-term benefits can come from doing what we fear, even if it doesn’t work out 100%. A modern version of this exercise is described in detail in this TED talk and blog post by author Tim Ferriss.

In my experience, from all of the above will emerge a great option to try out, a great path to walk down. It may be scary. It may be uncertain. The final piece of advice is this: Just do it, and move on. Don’t look back to the other options or agonize about “what ifs”. Just. Do. It. If the path we have to walk is still too big, too complex or too scary, we can break it down into a checklist of smaller steps5,6 (so that we can see ourselves making progress towards it), and start with the first thing in the checklist.

But don’t wait. Start today.

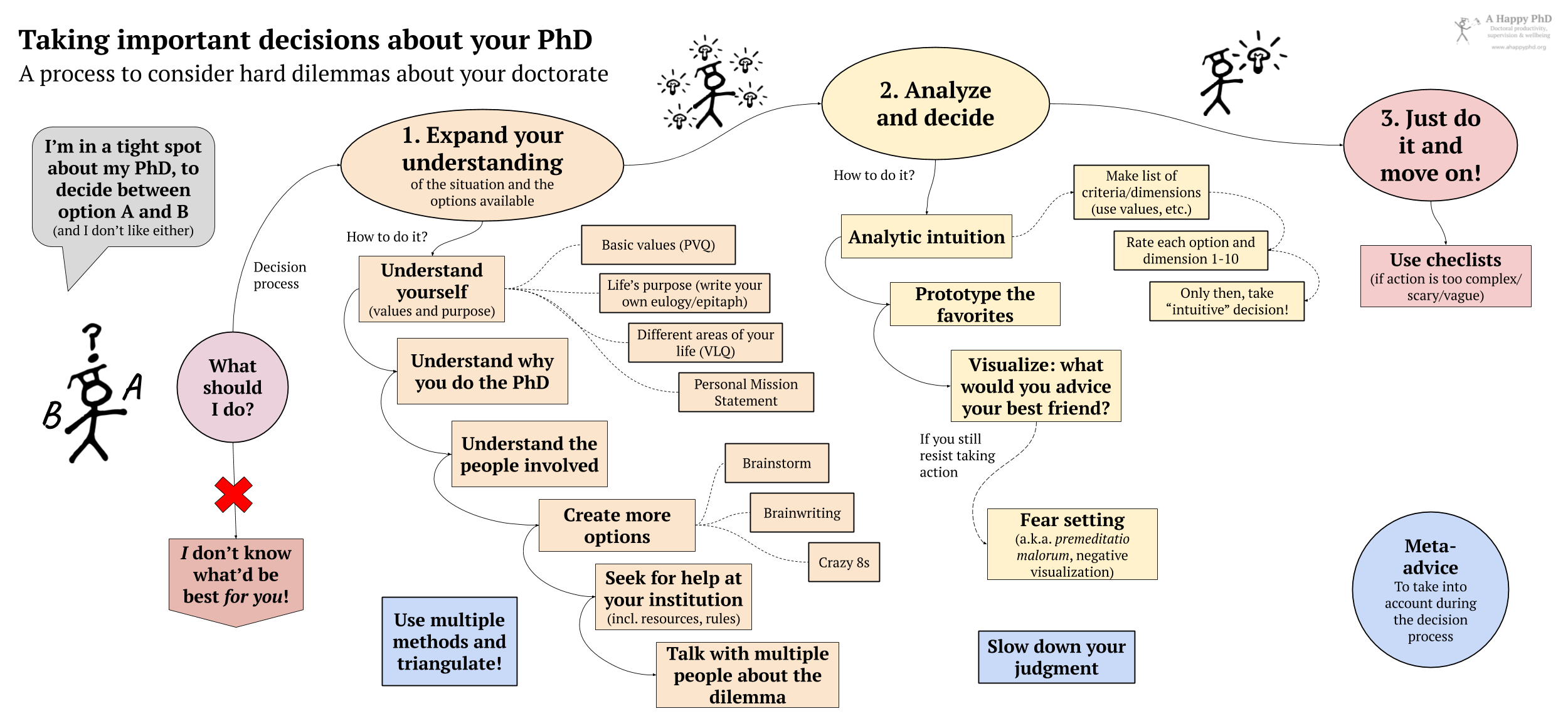

That’s it. The graph below summarizes these steps and exercises:

Epilogue: What if we were wrong, after all?

What if we start walking that path we carefully chose and, after some weeks, or months (or years!) we find out that it doesn’t work quite as we expected, or that it doesn’t satisfy us as much as we thought? Well, guess what: we can take another decision then. After we have tried that path for a time, maybe we will understand ourselves better, or know better the people and the situation around us, or how those places, fields or communities work. We will then be wiser.

If we took the decision with the best knowledge we got from the steps above, then there is no space for regrets. No decision is taken in vain.

No path is walked in vain.

We will have learned something. As PhD students (and as humans), we are learning throughout our whole life.

Next time, we will take even better decisions.

Are you facing a hard dilemma in your PhD right now? Do you have other decision-making tips and tricks you want to share with fellow PhD students? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header photo by Graham Hale.

-

Maule, A. J., & Edland, A. C. (1997). The effects of time pressure on human judgment and decision making. Decision Making: Cognitive Models and Explanations, 189–204. ↩︎

-

The interview is really good in general, if you are at all interested in human psychology (and you probably should be, if you are human ;)), as it covers not only decision making, but also many other aspects of how we think and act, from negotiation to behavior change. ↩︎

-

Gilbert, D. (2009). Stumbling on happiness. Vintage Canada. ↩︎

-

This prototyping tip and some of the other ideas of these posts are taken from a nice book on career and life advice: Burnett, W., & Evans, D. J. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life. Knopf. ↩︎

-

Jackson, C. K., & Schneider, H. S. (2015). Checklists and Worker Behavior: A Field Experiment. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(4), 136–168. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20140044 ↩︎

-

Gawande, A. (2010). Checklist manifesto, the. Penguin Books India. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.