POSTS

On Sleep

by Luis P. Prieto, - 13 minutes read - 2639 wordsIs your PhD giving you beautiful dreams or horrible nightmares? In either case, you probably should be getting more of them. Sleep (or, rather, lack of sleep) is one of the best-known and most consistent risk factors related to depression, anxiety, and host of other mental and physical health issues. It is also one of the factors (mostly) under our control – even if it often gets the back seat with respect to other priorities like work, social life, family, or the latest season of our favorite TV show. In this post, I review some of the (very extense, and rather terrifying) research about the effects that lack of sleep has on humans in general, and PhD students in particular. The post also points you to practices and resources to help you in sleeping not only longer, but also better. Keep your delicate mind and body machinery in optimal working condition!

I still remember the most sleep-deprived times during my doctorate: just at the very end, when we had set a hard deadline to submit the thesis so that I could defend in time to apply for a postdoctoral fellowship I had my eyes on. Thus, I was rushing to write the whole dissertation manuscript in three months.

Well, I don’t actually remember much from those hazy days myself. Mostly, I remember what others told me about that time: the few people that saw me during those three months say that I was just a shadow, a phantom of a man wandering occasionally around the house, barely talking. From what I’ve seen of others when sleep-deprived, probably that was accurate.

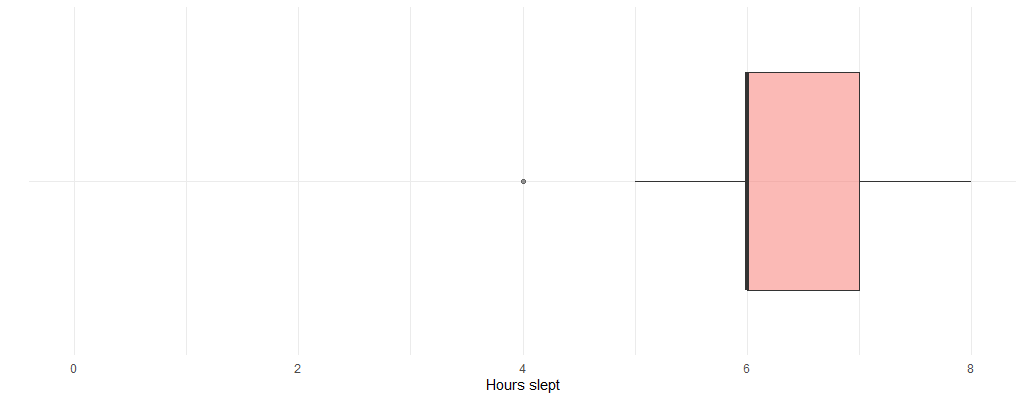

I know for a fact that mine was not an isolated case. Several studies have shown a commonplace lack of sleep among graduate students: for instance, in a study of n=65 grad students in the US1, they reported sleeping an average of 6h40min each night, with a deviation of more than one hour (meaning that people taking less than 6 hours of sleep on average were not uncommon). A more recent study of 2,683 graduate students (including doctoral students) gave a similar average of 6.4 hours of sleep a night2. In a recent workshop with doctoral students, we asked them to actually track their sleep3 for a couple of days. Below you can see the distribution of answers of n=9 of them – the median value is 6 hours of sleep. And, of course, this is not a problem exclusive to PhD students: post-doctoral academics often suffer from the same chronic lack of sleep.

Why everybody should sleep more

OK, so let’s assume you are one of these (many) people who get around 6 hours of sleep each night. Is that really so bad? should you try to change your lifestyle and routines to add the additional recommended 1-2 hours? Hmmm…, that seems like a lot of hassle… where are those hours going to come from anyways?

Maybe one of the best responses to those questions is Matthew Walker’s book Why we sleep4. In this book, the neuroscientist and sleep researcher at UC Berkeley gives a sweeping view of the latest research regarding the physical and mental processes that are impacted by sleep (tl;dr: almost all of them), and what are the effects of sleeping less than the recommended 7–9 hours of sleep. Here is just a rapid-fire list of things skimmed from the book:

If you sleep less than a full night of sleep, you will…

- … have more cardiac arrests (4–5 times more risk, if you normally sleep 6 hours or less)5

- … have higher risk of type 2 diabetes

- … be more likely to develop cancer (40% more risk if you normally sleep 6 hours of less)

- … have more risk of a car accident (almost twice the risk if you sleept today 5–6 hours; 11 times more risk if you slept less than 4 hours)6

- … (if you are a man) have lower testosterone (similar to aging 10-15 years), lower sperm count (29% less) and smaller testicles

- … (if you are a woman) have lower follicular-releasing hormones related to conception (20% less), and higher chances of suffering miscarriages in the first trimester

- … have more genetic defects and more deteriorated telomeres in your chromosomes (which is related to aging)

- … just eat more (after 10 days at 5–6 hours of sleep, we are hungrier and tend to eat 300 more calories, which normally don’t get spent)

- … have worse effects from dieting (losing more lean muscle mass, rather than fat)

- … look objectively uglier to other people (!?)

- … memorize, and generally learn, less (20–40% worse retention for 6h or less of sleep)

- … be more reactive to emotional stimuli, and be worse in decoding other people’s facial expressions (biasing your perceptions towards fear)

- … work less productively (i.e. you will need more hours to do the same task), which in turn tends to lead to longer work hours, hence even shorter sleep, then even less productivity, etc.

- … like your job less, be less motivated, lazier, and more prone to show unethical behaviors (yeah, why not tweak a bit those experiment results?)

Take a moment to think about it. Read the list again, if didn’t sink in. Do you really want all that?

Maybe the most impacting aspect of the book for me was the amount of research indicating not just that “more sleep is better” (which is well known, but also quite abstract and does not compel me to change my habits and lifestyle). Rather, that researchers have very strong proof of the concrete, quantified adverse effects of even small quantities of sleeplessness: pulling a single all-nighter, or sleeping 6h a day routinely… and how it multiplies chances of a car crash by 11!

The really terrifying thing is how widespread and ignored these effects/risks are (who has not done these things sometime during their thesis?).

Why PhD students should sleep more

This leads us to another question: yes, lack of sleep can have bad effects on the general population (and probably some of that research above was done on non-representative samples, e.g., of undergrads around Berkeley). Is there really concrete, hard evidence that sleeping a bit less can really impact you, as a doctoral student, and your main goal right now (e.g., finishing your thesis)?

It turns out there is some research on that, too. Not a lot, but some.

For instance, in the previously-mentioned study of 65 US graduate students1, sleep was significantly (and negatively) correlated with stress (people that slept less, were more stressed). Another study of 136 French PhD students7 found that sleep problems were associated with symptoms of stress, depression and anxiety. Another recent study of 488 US grad students of psychology8 found that sleep hygiene habits (the practices that lead to a good night of high-quality sleep – see below) was more highly (and negatively) correlated with stress than other factors such as social support! Similarly, another study on 1,923 French PhD students9 found that the self-reported quality of sleep explained as much variance in the stress as all the other factors (sex, age, year of thesis, financing, satisfaction with supervision, physical activity) together10!

How to make your sleep better

I hope by now I have scared convinced you that sleep is very important if you want to finish your thesis on time and in a good mental state. But, how do you get better sleep? it is not like anyone desires bad sleep.

The thing is, sleep is related to many of our lifestyle habits, which are surprisingly hard to change. As it turns out, humans appear to be the only animals that restrict their sleep voluntarily – and the modern world provides us with many temptations, opportunities and challenges which often take precedence over sleep, voluntarily or not (from unlimited amounts of entertainment at our fingertips, to bright lighting at night, or that noisy disco club downstairs).

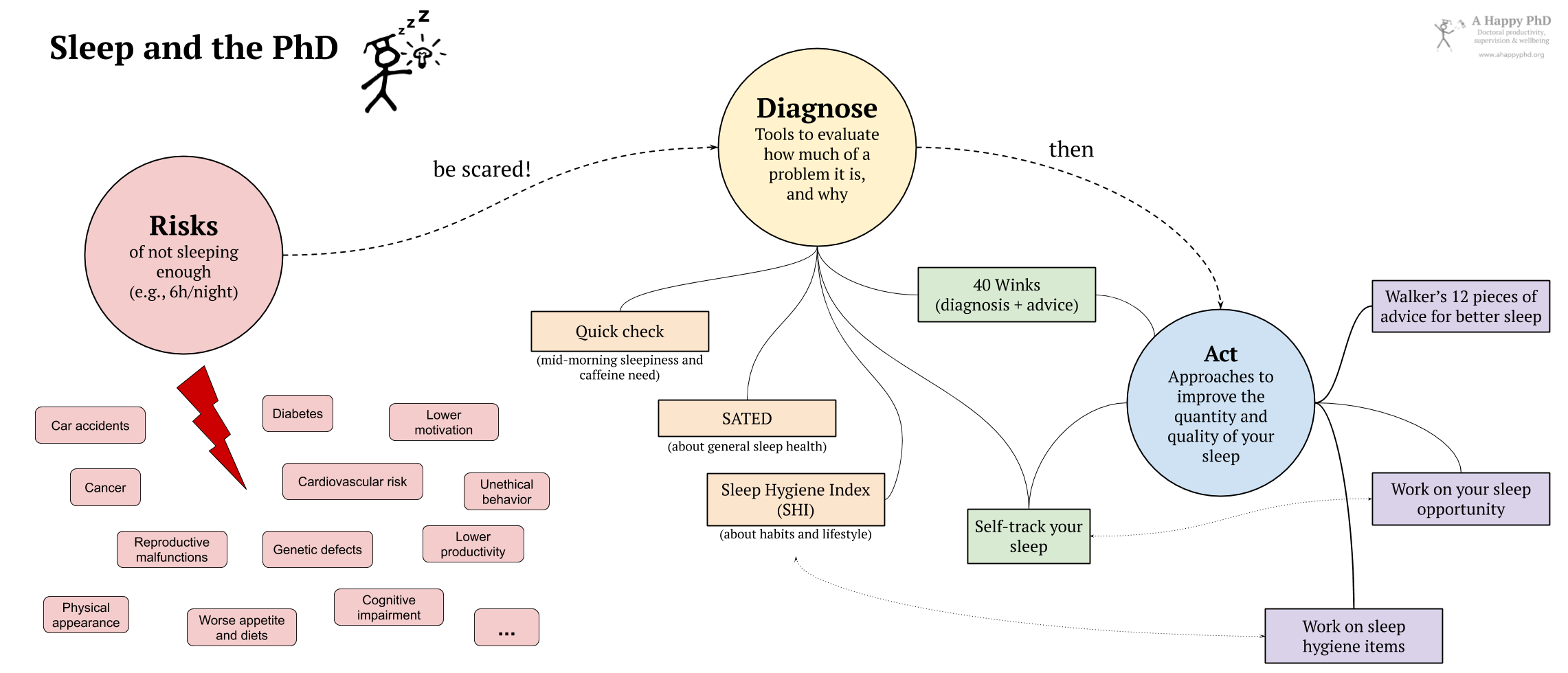

As we did in the happiness in the lab series, here I also propose, as a first step, that you diagnose how much this is a problem for you. You can try one or more of the following methods:

-

The “quick check”: Do you tend to feel sleepy in the midmorning (10-11am)? can you function optimally before noon without caffein? If the answers were yes or no (respectively), probably you are not getting enough sleep and/or you are self-medicating it with caffeine.

-

SATED questionnaire: If you want a slightly longer check (but still under two minutes), you can try Buysse’s SATED questionnaire11, which gives you a simple “sleep health” rating between 0–10.

-

Sleep Hygiene Index: Slightly longer, and more focused on the idea of sleep hygiene (environment and habits that make good quality sleep more likely), you can try this questionnaire12 which already provides implicitly quite a few actionable ideas for making your sleep longer and of better quality.

-

40 Winks: If you have a bit more time to dedicate to this crucial aspect of your life (maybe 30 mins), you can try ClearerThinking’s 40 Winks web app, which integrates both a quite detailed assessment of your sleep quality and potential causes for poor sleep, and the giving of advice for habits that could help you with your sleep (often overlapping with the sleep hygiene concepts mentioned above).

-

Self-tracking and sleep opportunity: One of the aspects that maybe the self-reporting questionnaires above overlook a bit is the fact that we are not very good at giving accurate estimations of what we did in the past or what we often do (especially, if we are sleepy). This is also related with the issue of sleep opportunity: how much time do we really give ourselves to be in bed, not doing anything, ready to sleep. For many of us, insomnia is not the problem, it is just that we are too busy and we just don’t set aside enough time to sleep. One small practice that helped me diagnose this in my own life was to self-track my sleep on a daily basis. If you have a fitness tracker (e.g., a Fitbit or similar), you may already have this kind of data. Otherwise, just do as I do, and note down in your paper journal or a spreadsheet, every day shortly after you wake up, how many hours you gave yourself today to sleep. It may prove eye-opening when you summarize the data for, say, one month of doing this.

Once you have a first idea of whether sleeping is a problem for you, the next step is to act upon this information, i.e., change things in your environment or your habits, so that you can sleep better every night. This is the really tricky thing, as it involves quite a bit of self-awareness, self-control and, very often, negotiating with other people as well (e.g., can you get your flatmates or spouse on board to go to bed earlier?). Here are some ideas to decide what changes would be most effective for you:

- Just the notion of sleep hygiene as described in the SHI questionnaire can provide you with a good starting point: for which of the questions do you have a low score? which ones do you think are easier to change, taking into account your situation and environment? try changing those that best fit both criteria.

- Walker’s book4 provides an appendix with 12 pieces of good advice (which overlap a lot with the previous sleep hygiene tips). Among that advice, he considers the adherence to a constant time for bedtime and waking up, as the most important practice to enforce, if one has to choose (well, probably after giving yourself 7-9 hours of sleep opportunity, which is a necessary condition).

- As mentioned above, the 40 Winks app will provide research-based personalized assessment and suggestion of practices for better sleep, adapted to your particular situation. Worth trying if you have some time and you are serious about this (and you should be!).

- If you saw that your main problem is not so much hygiene but rather your sleep opportunity, my advice is to work on that specifically: look at your calendar/schedule, see what the main friction points are that make you go to bed late and/or wake up early; talk around with the people that have an influence on them… and continue self-tracking as you make changes in your life, to see if the amount of sleep you give yourself gets better.

Back to the last bits of my thesis, in the end I managed to meet the deadline and submit my thesis on time… but it costed me quite some days of long work hours, and nights of short, poor sleep. Sadly, the postdoctoral fellowship I was aspiring to, did not come. Was it worth it to spend all that time tired and stressed over it? Or worse, would I have been more productive, would I have submitted a better application for the fellowship, if I had kept a more reasonable sleeping schedule?

One cannot but wonder.

Are you sleep-deprived? Suffering from insomnia? Do you have other tips or advice to make your sleep longer and better during the thesis years? Let us know in the comments below.

-

McKinzie, C., Burgoon, E., Altamura, V., & Bishop, C. (2006). Exploring the effect of stress on mood, self-esteem, and daily habits with psychology graduate students. Psychological Reports, 99(2), 439–448. ↩︎

-

Allen, H. K., Barrall, A. L., Vincent, K. B., & Arria, A. M. (2020). Stress and Burnout Among Graduate Students: Moderation by Sleep Duration and Quality. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09867-8. ↩︎

-

I’m a bit skeptical of studies where people just report what they do on average, since our memory is very prone to biases (if I think I sleep enough, probably that will skew my estimation towards higher values – and viceversa), and not very good at statistics (is the value I report really the average, or is it actually the mode, or something else?). ↩︎

-

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: The new science of sleep and dreams. Penguin UK. ↩︎

-

These and many of the following results take into account (i.e., control for) other confounding variables like alcohol consumption, smoking, age, gender, etc. ↩︎

-

And, if you think that you are used to sleeping less, or that you just need less sleep than other people, think again: there are also studies showing that this worsening of performance still exists despite the subjective feeling that we are performing OK, which becomes commonplace after a long time sleep-deprived. ↩︎

-

Marais, G. A., Shankland, R., Haag, P., Fiault, R., & Juniper, B. (2018). A Survey and a Positive Psychology Intervention on French PhD Student Well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 109–138. ↩︎

-

Myers, S. B., Sweeney, A. C., Popick, V., Wesley, K., Bordfeld, A., & Fingerhut, R. (2012). Self-care practices and perceived stress levels among psychology graduate students. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(1), 55. ↩︎

-

Haag, P., Shankland, R., Osin, E., Boujut, É., Cazalis, F., Bruno, A.-S., Vrignaud, P., & Gay, M.-C. (2018). Stress perçu et santé physique des doctorants dans les universités françaises. Pratiques Psychologiques, 24(1), 1–20. ↩︎

-

Another way to illustrate the model of stress from this study: having one-level better sleep (in a scale from 1–5) would almost compensate for both being one year behind on the thesis, and suddenly switching from being satisfied to being dissatisfied with your supervision, in terms of stress. ↩︎

-

Buysse, D. J. (2014). Sleep health: Can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep, 37(1), 9–17. ↩︎

-

Mastin, D. F., Bryson, J., & Corwyn, R. (2006). Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(3), 223–227. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.