POSTS

Supervisor Quickie: the Post-It Feedback Method

by Luis P. Prieto, - 6 minutes read - 1154 wordsHave you ever spent hours providing feedback over a colleague’s (or a student’s) paper? And have you ever found afterwards that many of your carefully-crafted, thoughtful comments had been ignored? In this “quickie” post for supervisors (or for anyone giving internal feedback), I share a small trick that I use lately to avoid these situations… and get better outcomes for everyone involved.

Dripping with red ink

I remember the first time I read this PhD comics strip. I had just received one of my early paper drafts back from my supervisors. When I’d sent it to them, I thought it was almost ready for submission. Yet, there they were, several dozen comments in red ink over the paper printout.

Ouch.

At the time, I had felt down and discouraged, but at least the comic strip helped me understand that I was not alone. What happened next? I don’t really remember, but here’s my best guess: I went through most of the comments (especially, the easy ones), and tried to solve them in the quickest way possible. It was just too much emotional and cognitive pain to redo the text that I had so effortfully crafted. Some of the comments, I’m sure, I never addressed (maybe consciously, more probably semi-unconsciously). Yet, there is one question that I did not pose myself until years later:

How had my supervisors felt when they saw that the next draft still contained some of the same errors?

More than 10 years have passed since then. I am now the supervisor of five PhD students (and I have provided feedback to many, many more). From the other side of the fence, now I have the answer: at times, I feel ignored and frustrated. (At other times, let’s be honest, I don’t even remember what comments I’d made).

Recently, I came across a paper showing that this sort of feedback overflow (and ignoring) is quite common1. As supervisors, we too often try to make students’ papers exactly like we would write them. Or we secretly fear what others will think of us if a less-than-perfect paper goes out into the world with our name attached to it. As students, the deluge of critical feedback is emotionally difficult (or plain confusing). Glossing over some comments is thus one of the subtle mechanisms that our minds have to protect our (already fragile and impostor-syndromey) egos.

Is there a way to escape this situation in which we give too much feedback that then gets ignored? Can we at the same time avoid breaking doctoral students’ already “fragile shell of success”?1 Here’s the trick I use lately to counter this situation in my own research and supervision…

An alternative way to give feedback to your PhD students (or peers)

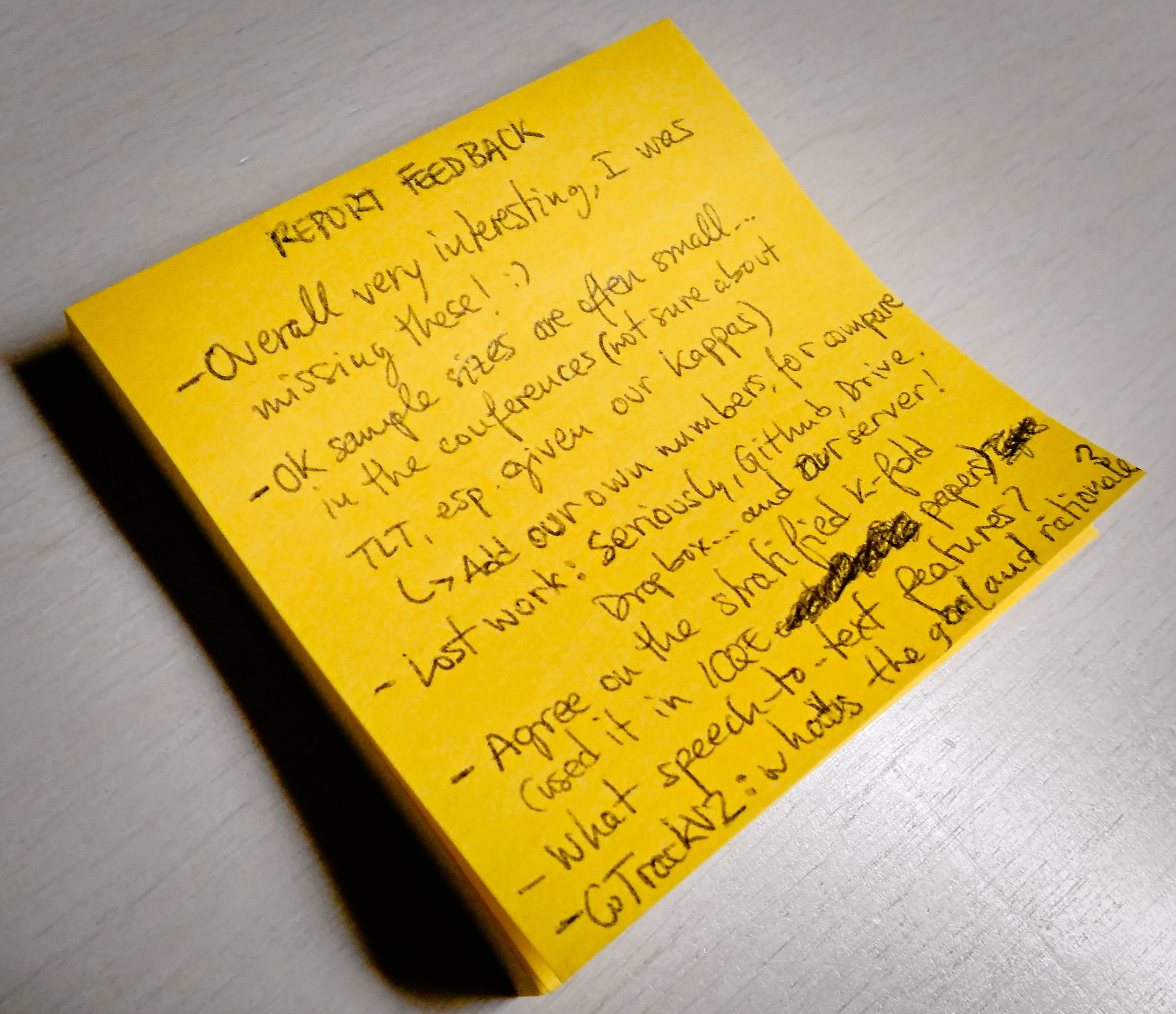

- Take a post-it (the normal-sized ones, not the big ones) and a pen. Yes, even if the document is on Google Docs or some other digital platform.

- As you read, control the impulse of quick-reaction commenting on small details, vocabulary or clumsy figures of speech (tools like Google Docs make this exceedingly easy and tempting). Look for the broad, structural, fundamental problems that break the paper. Or recurrent issues that repeat throughout the text.

- When you detect such an important issue, write a quick note down in the post-it (not a full sentence, just a bullet-point memory aid)

- You are not allowed to exceed the space of the post-it (on both sides, if it comes to that). This limits your notes to no more than ten-ish feedback items.

- Only after you finish reading, you can start writing the actual feedback, based on the post-it notes. The goal is to craft really effective feedback that helps the other person learn and be motivated to move forward. Classic rules for better feedback include:

- Be clear and specific (”????” is not a useful comment).

- Be constructive. Don’t just point out problems (feedback); spend more effort suggesting alternatives, next steps or new ways to think about the text (feedforward)1,2.

- Never make personal attributions (“you are a bad writer”).

- Paint errors as a common and natural part of the learning process (not something to fear)3.

- Consider the person’s current and self-perceived ability. Novices will need more encouragement and feedforward. More advanced writers can probably withstand more direct feedback4

- Et cetera. Think what your comment will bring as an outcome, both in making this paper better and making future papers by this person better. How can we help them think and write clearly? If you (like me) never had a proper feedback education, go back and read education classics like Hattie’s work3,4.

Doing feedback this way helps me revise papers faster, and focuses my energy on the important stuff. What’s important? the ideas in the paper and the evidence behind them… and making my feedback an effective tool to help others learn.

At least, I have found this method better than the old giving up, frustrated, after 50 small comments on the first page of a document.

Cautions, caveats and other qualms

Using this method requires a change, both in our practice and other people’s expectations. It will be hard at the beginning. Also, pay attention when not to use it:

- When giving your feedback, highlight that it isn’t all possible comments, just the most important ones. Avoid the false expectation that, once those are solved, the paper is perfect. You could even say explicitly how many iteration rounds you think are left (or use a 1-10 readiness scale).

- This post-it feedback method works best with internal research reports, or in iterative paper writing processes (like the one I have recommended before in this blog).

- Do not hold up on feedback about the truly important things, like methodological rigor and other scientific must-haves. If you plan to sign as a co-author, you accept responsibility for what is said in the paper!

- In summary, use your judgement when deciding if this method is appropriate. It may not be useful in the last revision round of a dissertation (when polishing many tiny details is actually the point).

Happy revising!

Do you have any other tips or tricks when giving feedback to your PhD students or your peers? Tell us in the comment section below!

Header image via Pixy.

-

Carter, S., & Kumar, V. (2017). ‘Ignoring me is part of learning’: Supervisory feedback on doctoral writing. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(1), 68–75. ↩︎

-

Budworth, M.-H., Latham, G. P., & Manroop, L. (2015). Looking forward to performance improvement: A field test of the feedforward interview for performance management. Human Resource Management, 54(1), 45–54. ↩︎

-

Hattie, J. A., & Yates, G. C. (2014). Using feedback to promote learning. In Applying Science of Learning in Education (pp. 45–58). http://teachpsych.org/resources/documents/ebooks/asle2014.pdf#page=51 ↩︎

-

Brooks, C., Carroll, A., Gillies, R. M., & Hattie, J. (2019). A matrix of feedback for learning. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(4), 2. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.