POSTS

Monday mantra #3: When you have too many open fronts

by Luis P. Prieto, - 8 minutes read - 1613 wordsHave you ever felt that you have too many threads open in your research work, and you cannot seem to make substantial progress in any of them? You are not alone. After closing the long series of posts on “happiness in the lab”, a bit of a lighter read this week. In this post I give very short advice that you can use as a “mantra” for this and the coming weeks, somewhat related to staying productive – but with a twist.

But first off, a couple of housekeeping notes. I have put up a small post with the links to all the posts of the recent “Happiness in the lab” series, for easier reference and navigation.

Similarly, I have created another index page for the series of posts on writing research papers which I did in the beginnings of the blog. If you have not read them yet and you are writing a paper soon (which should cover about 100% of the PhD student and PhD advisor population), check them out!

Now, on to this week’s post…

This week, as I was hiding further and further down in my tortoise shell (a.k.a. the library) to finish and submit a paper, I also noticed something in my (scarce) conversations with colleagues and PhD students around me.

Everybody’s so busy.

Of course, it is always like this in research, right? you have to read papers, do your experiments, analyze data, do reports and actual papers, write funding proposals, prepare presentations for conferences, do your courses, or teach your courses, network to find collaborators, and actually do something as a collaboration… I get it. It’s a ton of different things. It was just weird how so many people around me uttered the words “doing too many things”, “not really advancing much”, or “sorry, I have work to do [talking about the weekend].”

This got me thinking, is there really a solution to this? What would be good advice here?

A short piece of long-term productivity advice

This slogan, attributed to designer Dieter Rams (one of the main designers behind the Braun brand of appliances), was uttered in the context of what good product design should be about: try to do just one thing really well, not fulfilling multiple functions crappily. This kind of design minimalism was then adopted by the likes of Apple (remember when the first iPod came out, with its single function and minimal controls?).

However, I came across this quote recently in a book titled Essentialism1 – which has nothing to do with design. In the book, Greg McKeown makes the point that, rather than doing a thousand different things to feel busy and important, we should do less things (those that are really important and meaningful), and do them really well. This advice is given as a solution to the problem of frazzlement and fragmented attention which many people seem to suffer in many modern knowledge work professions.

One metaphor I like in the book when referring to this problem, is that of the donkey faced with two piles of hay, that cannot decide which one to eat, and finally dies of hunger. Probably many PhD students and academics can relate to the donkey’s problems: you start the morning wanting to write the draft for your latest paper, but before that you check your email (in case something urgent popped up); two hours and 63 emails later, you finally get in front of the blank page. After two sentences, you find out that you don’t have a reference to back up a claim, so you spend another hour chasing that reference down the Google Scholar rabbit-hole. Then, you remember that you need to finish preparing next week’s lectures, and start doing that. A colleague passes by and asks you whether you finished the data analysis for the latest experiment. Oops, not really. You open the email to retrieve the link to the shared folder where the data was stored, but then you see two new special issue calls for papers that look interesting for your most recent rejected manuscript – better check whether the journals are any good…

You get the idea.

By the time you decide to close the day and head home, you have fought in 10 different fronts, didn’t have even time to go to the toilet, and achieved absolutely nothing. And that did not even include any family or social obligations, hobbies, unexpected events or emergencies. You could also throw in a bit of checking social media as well, if there were any gaps in your day.

But, but, you may cry, a good researcher needs to do all that, these days (even the social media bit) – and do them well!

Maybe yes. But doing it like this is just impossible. If somebody told you “be creative, but these are the 10 things you need to keep in mind at all times”, you would not be able to create anything, or function in any way. As productivity guru David Allen says, “your mind is for having ideas, not storing them”. And this sort of continuous short-task-switching forces our brains to keep everything in mind, just in case we switch again to it soon (which we perfectly might, given the speed of task change).

We tend to see productivity as “doing as many things as possible in as little time as possible” (so that we can fit more stuff to do later in that span of saved time). What the quote/mantra from Dieter Rams reminds us, is that productivity can also be about the pride of a work well done, the absorption of the lessons learned, the celebration of your achievement, the enjoyment of the process of doing it (which is essential to develop an interest and engagement about what we do).

But, but, you cry again, I still have to do all those 10 different things to be a good –a passable–researcher! No way I am going to do all that enjoyment stuff about all those 10 things. There is just not enough time. You have to choose: either do many things (crappily) or do one thing well… right?

Maybe. Maybe not.

I don’t have the master solution to this. Nobody has. But there are a couple of things that have helped me do “less, but better”:

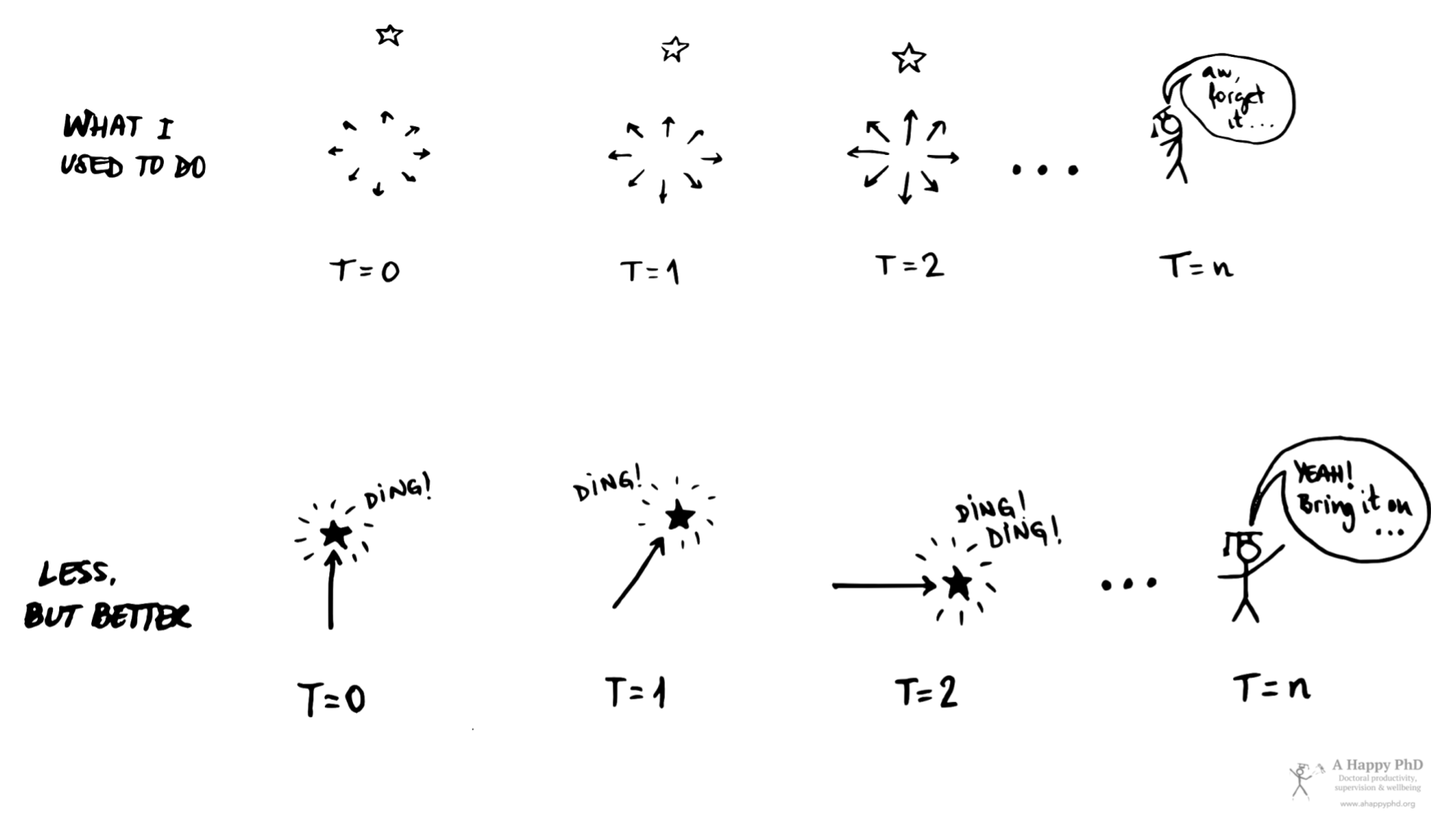

- Longer time-multiplexing: work on the 10 different things… by the end of the week, or by the end of the month, just not in the same day. The Pomodoro technique in its simplest form (i.e., working on something for 25 minutes, then switching to something else for another 25, etc.) does not cut it for me anymore2. Not for research stuff. In 25 minutes, I barely have enough time to remember where the hell I was last time I stopped working on the problem. These days, if I can, I spend the whole day working on one single thing (or different parts of a same problem, like analyzing data and writing the paper where I explain that analysis). And even this strategy would probably be useless if it were not for #2 below…

- End up these long stretches of work with a “tangible” outcome. Something that synthesizes your advances and new understanding about the problem. Maybe a paragraph summarizing the papers read, or an email to a colleague explaining your advances, or a document with your current ideas for the paper (even if it has more holes than a termite nest). Something you can carry with you, or share with others. Something you can quickly pick up next time to kickstart your thinking about the problem. Something you can reuse in the next task that builds upon this one. Because your research tasks should not be (or feel) disconnected from each other. Everything should be somehow tied to your central questions, you main contributions, etc. (remember the CQOCE diagram?).

Borrowing from a visual metaphor that appears in McKeown’s book, you could represent this two-punch combo strategy like this:

Not a perfect solution, for sure (I still have the impression I do less than is acceptable; and I don’t do those few things as well as I think I should). But I have learned to accept that those may be the limits of my productivity. Of productivity that does not feel like crap, at any rate.

Back to my situation this week, as everything else had to be thrown out of the window in the rush to meet the paper submission deadline, I noticed that my days were, if not more productive (I have the impression that I write slower and slower every year), at least less frazzled and hectic. And the warm, relaxing feeling of achievement in the small unproductive span of time just after the submission, was a welcome change from the constant pull of “doing the next short, possibly irrelevant thing”.

So, you know the drill: write down the mantra in a piece of paper; put it somewhere visible; come back to it every day when you get up, and multiple times during your workday.

May you do less, but better, more useful research.

Did this Monday Mantra help you? Do you have other tricks to help you do “less, but better”? Let me know in the comments section below!

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.