POSTS

Report from the trenches: of calendar tricks and time scarcity

by Luis P. Prieto, - 15 minutes read - 3082 wordsIn a previous post, I proposed the use of your favorite calendar app to store all your TO-DOs and avoid over-committing. I’ve been trying this productivity trick on myself for the past few months. In this new kind of blog post, I report on the results of this self-experiment, and the effect it has had on my own productivity and wellbeing. I also provide some practical tips and tricks, in case you want to try it out for yourself. TL;DR: It works… if you are a bit careful.

Reports from the trenches

I have been blogging here about productivity and wellbeing in the PhD and academia for about a year now. This might make you think that I must be very productive and super-happy myself, right? Well, not really, and not always. I am, however, deeply interested in these topics, including how they apply to my own situation. So, aside from reading a lot of research and other materials on these issues and writing about them, I also try them out for myself, to see what are the effects. I do a lot of self-experimentation.

Why?? Don’t you trust the findings of researchers or the advice of experts?

Well, yes, I do – but I am also wary of the wide inter-subject variability that many of these studies show. We are all different in so many ways (from genetics to education, culture, or life experiences), and we live in unique circumstances. Take, for example, the effects of mindfulness meditation to reduce the stress and anxiety of PhD students. If you read a recent study like Barry et al. (2018), you see that the researchers found a statistically-significant reduction in depression symptoms… on average. However, if you look at the spread of the difference in depression symptoms before-after the mindfulness course, you can see that, even if the average effect is positive, it is also not uncommon to find participants for whom the effect was actually negative. For me, the average positive effect marks that it is something worth trying, a starting point or a working hypothesis. But, what if you had been one of the negative-effect people? would you still take up this practice? I bet you wouldn’t – and for a good reason. That’s why I like the old Buddhist idea of not just going by reports, and trying for yourself.

That’s the idea of this new kind of post in the blog (the “report from the trenches”): I try out some of the practices and ideas that I have mentioned in the blog, apply them to my own life, and report briefly and informally about the results, in the hope that this will help you out1. This, of course, is no guarantee that these tricks, these practices, will work for you. It may only provide a (very small) bit of additional evidence, and give you some ideas on how, or where, to start.

Of calendar tricks…

The context. For the past few years, I considered myself a reasonably organized person. However, there was one thing that was bothering me somewhat: in my weekly and daily reviews, I noticed that many of my TO-DOs, even the few ones set to be done for a single day, were still undone by the end of the day, or delayed for another day (often indefinitely). Furthermore, my “general to-do list” of things I wanted to accomplish, continued growing and growing. This, of course, meant that I was routinely miscalculating the time it took to do things, which led to over-committing, which in turn led to a vague feeling of anxiety and overwhelm, which I tried to ignore. Then, in a productivity workshop we ran in a winter school for doctoral students, this visiting professor gave us the idea (which had served him well for years) of ditching TO-DO lists altogether and just using the calendar app to hold all tasks, with an associated time slot (see the previous post where I mentioned this, and also below).

What I was doing before (just to clarify the change before/after the experiment). Basically, I was using my calendar app (Google Calendar) to store mostly meetings and appointments2. Then, I had an overall (and quite long) TO-DO list with all the tasks I needed to do in the future (these were rather concrete tasks and projects I had committed to doing, not vague things I wanted to do someday maybe… those were kept in a separate list). Finally, according to Levels 1 and 2 of the practices to avoid TO-DO list overwhelm, I did a smaller list of tasks for the present day (drawing from the overall TO-DOs, or recent emails, etc.), marking 1-3 of them as the Most Important Tasks (MITs). This smaller list I normally kept on my notebook (which I try to keep with me when I’m working).

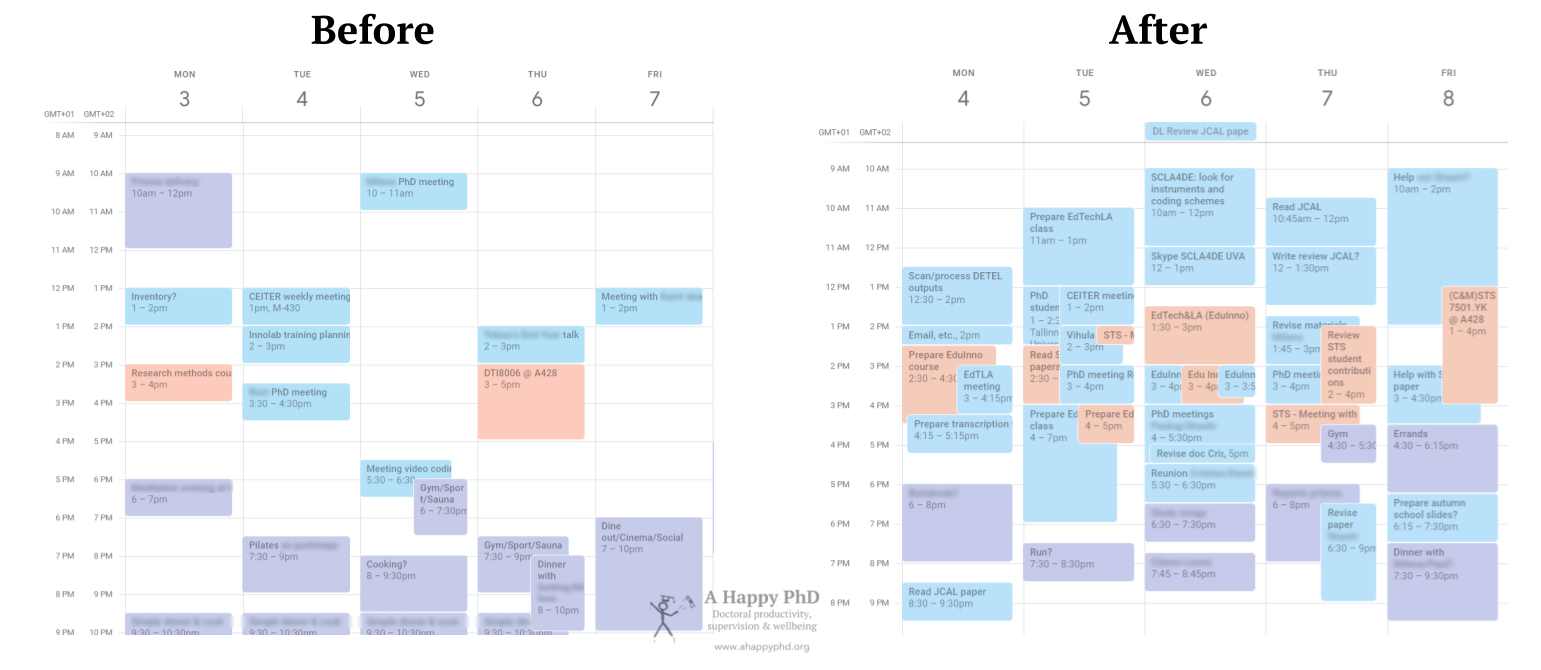

What I have done during the experiment. About eight months ago, I did the switch to the Level 3 practices in the aforementioned post. I emptied my overall backlog of TO-DOs, assigning them a time and a duration, and adding them to my calendar. For those tasks that were too large or too vague to put in the calendar, at least I put a slot in the calendar to scope the project and decide next steps/tasks to do about them (which would again go to the calendar). Then, I burned that cursed, overlong list that had been haunting me for years (well, no, I actually threw it to the recycling bin) – and, boy, did that feel good! Now, every new task I need to do, every new request, everything, goes, with a starting and ending time, into the calendar some concrete day in the future. If it is very urgent and I need to do it on a fully-booked day, then something has to go out, or be moved to another free slot/day. That simple. Quite importantly, I also update the calendar during the day (up to the closest 15-minute chunk, don’t overdo this), to reflect what I actually did, and the times when I actually started and ended the task (more on this later). This means that I have to keep the calendar handy at all times when I’m working3. Interestingly, I still keep the tasks and MITs for the day, taken from the calendar, in my paper-based notebook – even if it is redundant4. How does my calendar look like now? Please compare the two screenshots below, from before and after the change:

How my calendar looked before (left) and after I started employing the calendar to store all my TO-DOs (right)

But… does it work?

The good. There are quite a few things I found beneficial about this new approach:

- I am getting much better at planning realistically my days, and also at understanding how much time different kinds of tasks actually take (e.g., I was under the impression that I could review a paper in about one hour; now I know that it is more like 4-8 hours, depending on the paper’s length). I’m still not perfect at this, but for sure much better than before.

- I over-commit less. Related to the previous point, now I am painfully aware of my productivity limitations. Together with the fact that there is a limited number of hours in a day (and a limited number of hours I want to work in a day, in order to stay sane and productive), now I have a clearer idea of what I can achieve by when. When an invitation for a project or other “optional task” comes my way, attached with a deadline, I can make a clearer judgment and decline it, if that’s the appropriate thing to do.

- It is visual. At a glance, I can see how a certain day or week looks like in terms of busyness, and take quick decisions. Much better than just looking at the number of TO-DO items, which have no durations associated with them.

- Another beneficial effect, which I had not anticipated, is that this method hides a lot of the anxiety-inducing complexity and endlessness that the ever-growing TO-DO list was inducing (as long as you keep yourself in “Week mode” or “Day mode”, you never see the fact that you have tons of tasks pending – just don’t go into “agenda mode”!). As they say, out of sight, out of mind.

- It is just simpler. I have to keep track and maintain one less list (the big overall TO-DO list, which had to get pruned periodically to fit into a reasonable size, is now gone).

- I now have quite good data about what I do with my time. If later on I want to report my activities, or re-evaluate if I am spending too much time on, say, meetings, I can easily check the calendar and see if I’m deluding myself, or exactly how bad is the problem.

The bad. No trick is without its costs and downsides, and this is no exception:

- There is a cost to keeping the calendar running like this, moving blocks of time around every time there is a change of plans or a new thing comes in. Especially, there is a cost to adjusting the time slots to what I actually did (vs. my original plan) several times during the day. But normally this cost is on the order of seconds.

- You need to have the calendar on view or quickly accessible at all times (so you may need to re-structure some of your routines, how you work, etc.). In my case, changes were minimal, since I was already using the calendar app quite frequently before the switch.

- Similarly, you become tremendously dependent on your calendar (all my knowledge of tasks, appointments, etc. gets offloaded to that app – so I don’t remember anymore anything about those by myself, almost). Your calendar has become a single point of failure (e.g., if you somehow delete it, or it is not accessible for whatever technical reason). That is maybe why I keep the daily tasks also on the paper notebook: as a (redundant) backup solution (at least, for what I wanted to do today) in case I don’t have the calendar at hand.

- I still over-schedule myself. The impulse to say yes to whatever comes my way still remains. I have fallen prey to the “I could fit that in, if I make this and this slot a bit shorter” syndrome sooo many times… However, reality kicks back in quite quickly, and by the end of the day I can see in the (updated) calendar that things still take the time they take, and inserting the new thing just kicked out something else (or made my hours longer than I want them to be).

The ugly? I have the indefinite feeling that this fiddling with slots in the calendar all day can lead to a loss of “big picture perspective”, as I focus a lot on the one-hour slots, rather than the multi-day projects that are important, but not urgent. Another interesting (or, should I say, insidious?) effect of this way of working is that it makes you acutely aware that your time is scarce. And this kind of realization (and the daily reminder that the calendar represents) is, apparently, a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the focus on the scarce resource sharpens your ability to manage it (i.e., I do feel like now I am more efficient with time, more aware of the trade-offs involved in accepting a new task, maybe because I am looking at a graphical representation of my time frequently). But, on the other hand, it also leads to a sort of “tunnel-vision” in which only the immediate danger to that resource is paid attention to (e.g., this week’s deadline, or cramming as many tasks as I can into today), in detriment of longer-term tasks, projects or behaviors. This is best explained in a book I read recently (Scarcity, by Mullainathan and Shafir5), which details several studies on how resource-deprived people tend to act in ways that we consider unwise, and why that may be. Quite an interesting read, from which I gleaned a few ideas (some of them mentioned in the actionable tips below, others to come in a separate post on our ubiquitous “time scarcity” in academia and research).

The verdict… and some actionable tips

So, should you try it or not? Overall, I’d say yes, the benefits outweigh the downsides for me, today. I plan to continue using it, and continue learning about my planning skills (or lack thereof) and over-commitment. However, anyone trying this should be mindful of the downsides I mentioned above. In case you want to try it out yourselves, here a few tips for making the most of it:

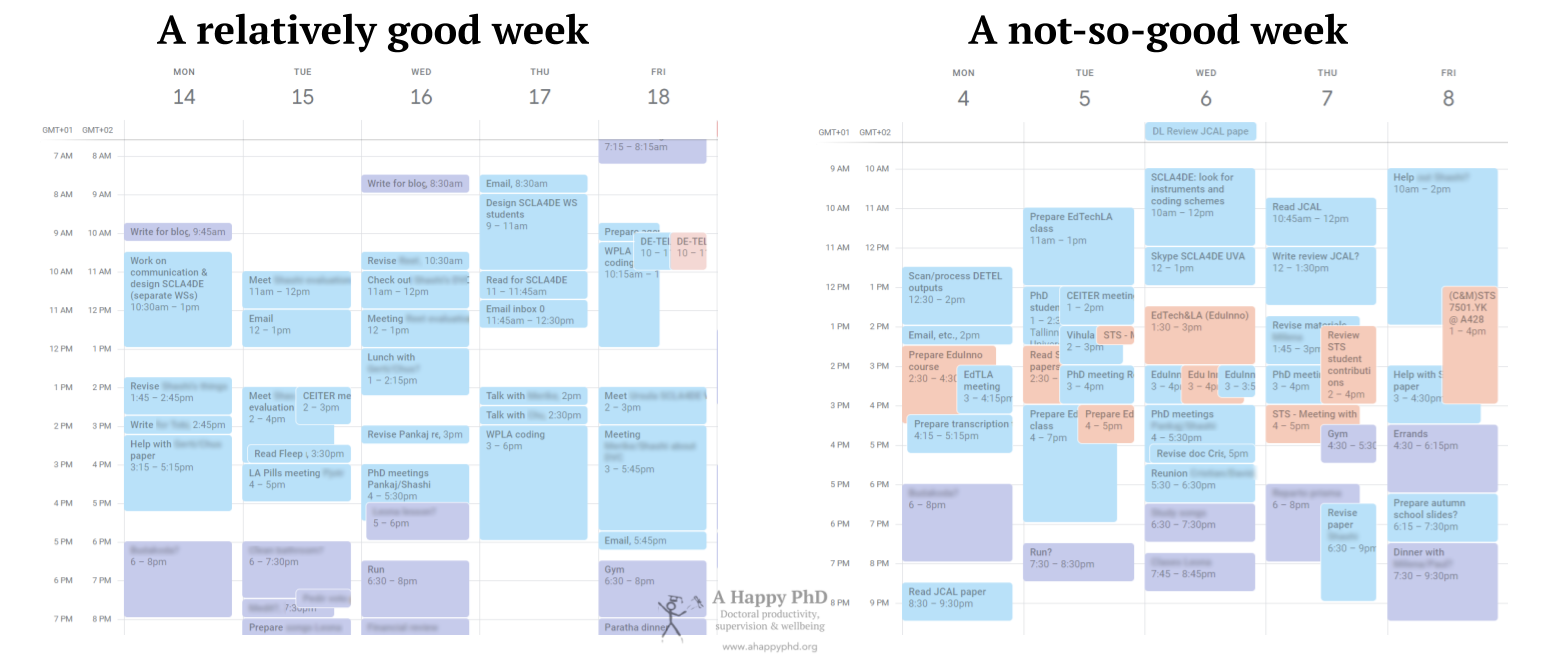

- Learn how to use your calendar app effectively. As with any craft, know your tools. Use different calendars (with different colors), not only for work vs. personal stuff (e.g., the purple vs. blue boxes in the pictures above), but also for joint specific projects or areas you may share with colleagues (e.g., my teaching and its preparation goes into a separate, red, calendar I share with my fellow co-teachers). Divide your tasks further into sub-calendars if you want to (e.g., for reading, writing, fieldwork tasks, etc.), so that you can see the week’s balance of different kinds of work just by squinting your eyes when looking at it. But do not spend too much time fiddling with this and making it “perfect”. Set something up in the beginning, and start working with it as soon as possible. The first step of setting up and moving your tasks there is the most painful one!

- Pair the calendar trick with weekly and quarterly reviews. While the calendar trick has helped me greatly in managing day-to-day work and making it more efficient and realistic, it can make you hyper-focus on fighting fires and churning out tasks that, at the end of the day, may not be that important. One antidote I found useful to get back the “big picture view”, is to be consistent with the habit of doing a weekly review (where you look at your longer-term goals and block time in the upcoming week’s calendar to tackle them). To make these weekly reviews work well, you need to have spent some time thinking out of your weekly calendar, gaining an even longer perspective – which is why I also do quarterly and/or yearly reviews, where I set goals and important projects for even longer time horizons (another post on those coming soon).

- Don’t get too obsessed. Yes, in this blog I seem to be all about productivity and such things, but do not overdo it to the point that you are more stressed by striving towards efficiency, than you were by being inefficient. During work trips, when my schedule is defined externally, I often do not use the calendar in the aforementioned way. Do not schedule your personal tasks and hobbies to-the-minute (but block time for those if you find it is too easy to forget them). I also do not schedule my holidays or any quality time I want to spend with family and friends.

- Leave slack. This is one of the main actionable lessons from the Scarcity book: for some systems to work properly, they need some slack (i.e., free, unused capacity). This is especially true when we know that unexpected events and shocks are actually frequent (e.g., new tasks popping up, a colleague stepping into our office asking for help, etc.). I find that my days are most realistic (and satisfying) if I leave 1-2 unscheduled hours to deal with the unexpected (see the picture below)6. This slack does not include the pauses for lunch, the leaving of 15 minutes between meetings (to get out, go to the bathroom, stretch your legs, etc.), or taking into account (amply) that you have to move around to get to your next appointments (sometimes, to different parts of the city). All this slack may seem wasteful, but it is a necessity if you want to avoid the “time scarcity mindset” and the classic planning fallacy (don’t worry, many other tasks will probably take more time than expected, and will happily consume that slack). And, if you eventually do have some time where you truly have nothing to do today, you can just fire up the calendar, pick a task from tomorrow, move it to today, and do it. That way, you are creating slack for your future selves – they will be tremendously grateful for that!

Side-by-side comparison of a relatively busy but satisfactory week (left), and a not-so-good week (right). Note on the right-side the smaller or non-existent lunch break spaces, parallel tasks/slots (I still thought I could multi-task!), shortening of tasks, all crammed together, and general lack of slack.

Have you tried to use your calendar as your to-do list? Did it work? Have you tried any other productivity trick recently? Let us know in the comments section below!

-

Of course, I am not the first to come up with this idea in the blogosphere. For example, I enjoyed quite a bit reading David Cain’s self-experiments at the Raptitude blog. ↩︎

-

In the last months before the switch, I often added to the calendar “meetings with myself”, for chunks of time that I wanted to dedicate to do focused work, like writing a paper or preparing courses I was teaching. So, in a sense, this was a sort of “transition” to the new way of doing things, rather than an abrupt change. ↩︎

-

Pro tip: the calendar app now is the home screen when I open my web browser; plus, I can access it easily from my phone as well. ↩︎

-

Why do I do this? especially when I am doing focused work, sometimes I don’t want to distract myself by opening the computer or the phone, which are full of potential attention-hijackers (think email, WhatsApp, Skype, etc.); plus, I just like the physicality of crossing off a TO-DO/MIT with a pen on the paper – go figure! ↩︎

-

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2013). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. Macmillan. ↩︎

-

Of course, it is unclear what is the direction of causality here. Are days with slack better because the slack itself has some beneficial consequences? Or are the busier days where no slack is possible (e.g., deadlines piling up) just going to be bad days nonetheless? ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.