POSTS

Journaling for the doctorate (I): Types and benefits

by Luis P. Prieto, - 14 minutes read - 2808 wordsDo you ever get the feeling, at the end of the day, that you have achieved nothing? or that days and weeks pass by, indistinguishable from one another, time slipping away like water between your fingers? Is your mind an unfocused maelstrom of swirling thoughts, ruminating again and again about the same worrying (or plain silly) things? Journaling has been proposed (both by ancient philosophers and modern researchers) as having many benefits, from dealing with stress and trauma, to just understanding ourselves a little better. But, can journaling be useful for us in facing the challenges of a PhD? In this post, I will take a look at the research on different kinds of journaling and what are their effects for mental and physical health.

NB: In this post I will talk mainly about journaling for personal, non-strictly-scientific use. There is, of course, another common journaling device in many research fields: the lab notebook. It goes without saying that keeping a lab notebook is highly recommended as well, especially if your field requires it!

I’ve never been a fan of journaling. Maybe I tried it for a while as a teenager, but the habit never stuck. I did write a sort of “lab notebook” during the first half of my PhD, but it fell down the wayside once my doctorate picked up speed and I rushed to complete its later publications and the dissertation itself1. Years later, well into my postdoc phase, I came across an interview with Jim Collins (ex-Stanford academic and business guru), in which he described how he used a short journal/spreadsheet and a simple rating system (every day was rated from -2 –really bad– to +2 –a really great day–) to understand his patterns of productivity and satisfaction. Since, back then, I was dealing with some motivational issues myself, I decided to try journaling out… and now it’s one of my keystone habits for productivity and sense-making (along with the weekly and quarterly reviews).

Keeping a diary in which you record events of the day, along with reflections or emotions that they prompted, is a practice with a long tradition, going back centuries to, at least, Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. Medieval mystics, poets, Venetian merchants, and even teenagers during the II World War… all seem to have gotten something out of this daily account of events. But, is keeping a journal anything more than a time-consuming hobby? Does journaling actually have psychological benefits? Is there a “best” way to keep a diary to maximize such benefits? I was quite curious about these questions myself. The rest of this post (and the next one) summarizes the answers I’ve found in the research literature.

Types of journaling and their (research-backed) benefits

Despite its popularity and long history, journaling practices have not been studied systematically until recently. What kinds of journaling have been studied, and what is the evidence that they work?

-

Probably the oldest systematic use of journaling for psychological benefits are “journal therapies”, which started around the 1960s. Although journaling is often used as an adjunct to many other psychotherapy approaches (from psychoanalysis to cognitive-behavioral therapy), there are therapies that use journaling almost exclusively. For instance, Ira Progoff’s “intensive journal method”2 is a series of exercises written in a notebook with sections, for different areas of the writer’s life (e.g., imagined written dialogues with people, to reflect on the writer’s relationships). I have not found, however, any systematic review of the evidence for its effectiveness. As with many clinical psychotherapy approaches, the idea seems to be: “try it out if you like the idea… if it works for you, it works – otherwise try something else”. In the same category of journal-based psychotherapies we can find cognitive-behavioral writing therapy (CBWT, also called “Interapy”, as it is often done through the Internet), a CBT variant developed to treat post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD)3. Interapy basically consists of writing exercises purposefully tailored to act upon our cognitive biases and perceptions (e.g., by writing about a traumatic event, and then getting therapist feedback and rewriting the event in specific ways to restructure how we think about that trauma), over a period of 5 weeks. This approach has some empirical evidence of benefits for people with such traumas (in terms of, e.g., anxiety and depression)4. One common feature of these journal therapy approaches is that doing them effectively normally requires guidance5,6 so it may not be easy to pull them off in a purely self-help manner… or it may even be detrimental7, if we are prone to rumination8

-

One of the most widely studied journaling practices is called “expressive writing” (writing about emotional or traumatic experiences, during several writing sessions, for about 15-30 minutes9. The initial studies and reviews on this practice found a variety of benefits of such writing, from academic performance to psychological wellbeing and even improved physiological markers9,10. Yet, as more studies (especially, randomized controlled trials) are accumulated and reviewed, more recent meta-analyses11,12,13,14 found small or no average effects. These reviews have also noted the large heterogeneity of results (i.e., effects may be quite different for different groups of people)14.

-

Another type of journaling intervention that has been studied a lot is “gratitude journaling” (a diary in which we focus specifically on things for which we are grateful). One popular form of this is the “three good things” exercise, in which we write about three particular things or events for which we are grateful, indicating also the concrete reasons or aspects for our gratitude and how the experience made us feel. The evidence-based benefits of this kind of practice are wide-ranging, including improvements on both positive (e.g., wellbeing, happiness, quality of relationships) and negative psychological variables (improvements in anxiety, stress or depression symptoms)15,16,17. There’s even evidence of benefits on physical health markers (e.g., sleep quality)18. Yet, these are not “miracle cures” that will make you instantly blissful: effect sizes in the studies are small to moderate, and some authors again mention the heterogeneity of effects (different strengths for different people)17.

-

A slightly different variant is “positive affect journaling”: writing a journal entry on a commonly used positive affect prompt (e.g., What are you thankful for? What did someone else do for you? What are any benefits or positive thoughts/feelings concerning a current stressful experience?). There is evidence of effects on anxiety or physical distress, but it is still emergent (studies are too small to make strong, generalizable claims)19,20. While the typical intervention takes about 15 minutes (over multiple days), there’s some evidence of health benefits for even shorter bouts of writing about a positive experience (or a traumatic one): as little as two minutes in two different days21 could be beneficial!

-

Journaling is, almost by definition, a retrospective exercise (i.e., we describe or reflect about a past event or experience). Yet, we could also think of a prospective counterpart to journaling: the setting of intentions or goals. This future-oriented reflection (basically, a formal goal-setting exercise) has shown benefits on academic performance (at least, in undergraduates)22. A shorter self-help intervention based on similar research evidence (but itself not studied systematically) are the “Two Minute Mornings”, popularized by writer Neil Pasricha: writing down each morning one regret, one gratitude, and 1-3 goals for the day (in a sense, similar to the daily review I proposed in a previous post).

-

There is, however, one aspect of journaling which I find critical, and which I haven’t found so many studies about (if you know of some, let me know!): the learning effects of journaling, and of reviewing periodically those journal entries (e.g., in a weekly review). This learning aspect (as explained by Jim Collins in the interview I mentioned at the beginning of the post) is actually what sold me on trying the practice: to understand better my patterns of work and wellbeing, and to do more of what works. This learning benefit of journaling is hinted at by large diary studies of knowledge workers23, and by studies on how self-affirmation writing exercises can help us be more resilient24. Some studies also show how reflective journaling, if adequately structured (including descriptions and evaluations of experiences, but also potential improvements for future regulation) has benefits for metacognitive awareness (our capacity to understand and regulate our own thinking)25. It is even starting to be studied as a student-directed tool to fight procrastination26 In my own (anecdotal) experience, writing these diary entries (and my reflecting upon reading a whole week of them) forces my brain to slow down to the speed of (hand)writing, and lets me examine my thinking without the logical jumps, biases and shortcuts we use in the everyday thought that happens only in our heads.

The bottom line: Should you journal?

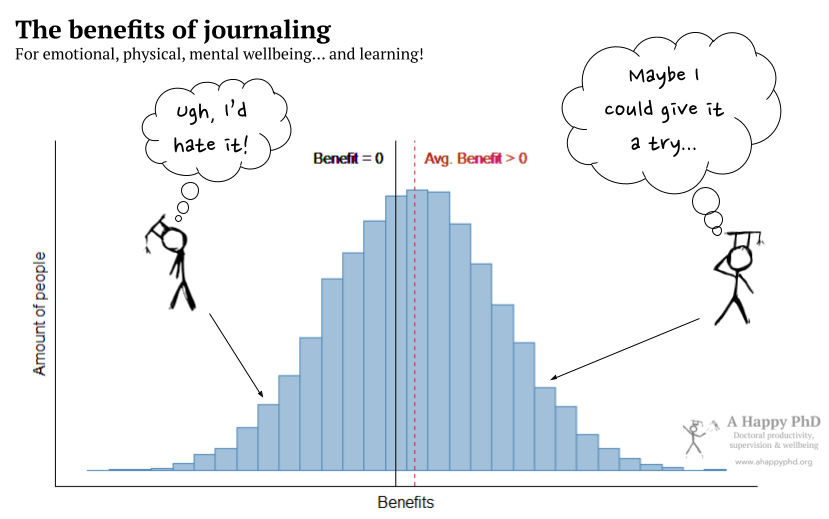

As we can see from the review of scientific evidence above, the potential benefits of journaling are multifarious… but the evidence for their benefits is not so clear-cut (with gratitude journaling showing maybe the most solid evidence of benefits). Some researchers have suggested that this heterogeneity may be due to individual factors like personal preference14: maybe how much journaling helps us depends on how much we hate (or love) the act of journaling, how useful we think it will be… and whether we are able to sustain it over time (a seemingly critical factor in achieving benefits17,19). This is represented in the (totally un-scientific) graph below:

This heterogeneity of effects is very common in human psychology. That’s probably why so many therapy approaches exist – every one of them may work on some people, but not on all people. This variance is also supported by my own experience working with PhD students: everyone’s doctorate is different (not only because of its topic and department/lab, but also due to individual differences in personality, beliefs, and many other contextual variables). Few things work for absolutely everyone. Indeed, this seems to be an ongoing debate in psychology and therapy: how much should research focus on finding average effects across a group of people (what they call the nomothetic approach) vs. finding particular dynamics, effects and interventions for an individual over time (the idiographic approach)27. Probably, both kinds of research are important and needed. The nomothetic perspective gives us good starting points that are likely to work. Yet, the idiographic perspective is crucial: what works specifically for us? We may find that the important question is not whether journaling helps everyone (on average), but rather, in which part of the distribution are we? The side of those that benefit, or those that do not? Only you can find that out.

My advice would be to look at these different kinds of journaling and ask: does any of them sound like something you would like to try (for a month or, potentially, indefinitely)? If so, give it a try for several weeks and then review the entries and how do you feel after doing it for a while. But you also may be wondering: how exactly do I do it? what are good journaling prompts and what are the best ways to keep a diary, according to this body of research? I will cover these nitty-gritty details about how to have a better chance of making your journaling effective, in the next post.

Do you journal or keep some kind of personal diary? if not, what is stopping you? if you do, do you follow one of the approaches above, or something else? what have you learned by doing it? Let us know in the comments section below!

-

In retrospect, the part of my PhD which I enjoyed the most coincided roughly with the time I was keeping that lab notebook in a wiki. Was that causal or casual? I’ll never know for sure, but the research in the rest of this post makes me think that giving in to time pressure and the “publish or perish” mentality, may not have been such a good idea, given my motivational problems later on… ↩︎

-

Progoff, I. (1977). At a journal workshop: The basic text and guide for using the Intensive Journal. Dialogue House Library. ↩︎

-

Pascoe, P. E. (2016). Using Patient Writings in Psychotherapy: Review of Evidence for Expressive Writing and Cognitive-Behavioral Writing Therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal, 11(3), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.110302 ↩︎

-

Lange, A., Rietdijk, D., Hudcovicova, M., van de Ven, J.-P., Schrieken, B., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2003). Interapy: A controlled randomized trial of the standardized treatment of posttraumatic stress through the internet. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(5), 901–909. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.901 ↩︎

-

Gellatly, J., Bower, P., Hennessy, S., Richards, D., Gilbody, S., & Lovell, K. (2007). What makes self-help interventions effective in the management of depressive symptoms? Meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine, 37(9), 1217–1228. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707000062 ↩︎

-

Williams, C., Wilson, P., Morrison, J., McMahon, A., Andrew, W., Allan, L., McConnachie, A., McNeill, Y., & Tansey, L. (2013). Guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression in Primary Care: A Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e52735. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052735 ↩︎

-

Haeffel, G. J. (2010). When self-help is no help: Traditional cognitive skills training does not prevent depressive symptoms in people who ruminate. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(2), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.016 ↩︎

-

We can check whether we have strong ruminative tendencies, using validated tests like the Rumination Response Scale, see Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504 ↩︎

-

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. ↩︎

-

Smyth, J. M. (1998). Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 174. ↩︎

-

Mogk, C., Otte, S., Reinhold-Hurley, B., & Kröner-Herwig, B. (2006). Health effects of expressive writing on stressful or traumatic experiences—A meta-analysis. Psycho-Social Medicine, 3, Doc06. ↩︎

-

Harris, A. H. S. (2006). Does expressive writing reduce health care utilization? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.243 ↩︎

-

Pavlacic, J. M., Buchanan, E. M., Maxwell, N. P., Hopke, T. G., & Schulenberg, S. E. (2019). A Meta-Analysis of Expressive Writing on Posttraumatic Stress, Posttraumatic Growth, and Quality of Life. Review of General Psychology, 23(2), 230–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019831645 ↩︎

-

Reinhold, M., Bürkner, P.-C., & Holling, H. (2018). Effects of expressive writing on depressive symptoms-A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(1), e12224. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12224 ↩︎

-

Davis, D. E., Choe, E., Meyers, J., Wade, N., Varjas, K., Gifford, A., Quinn, A., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Griffin, B. J., & Worthington, E. L. (2016). Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000107 ↩︎

-

Dickens, L. R. (2017). Using Gratitude to Promote Positive Change: A Series of Meta-Analyses Investigating the Effectiveness of Gratitude Interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(4), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1323638 ↩︎

-

Jans-Beken, L., Jacobs, N., Janssens, M., Peeters, S., Reijnders, J., Lechner, L., & Lataster, J. (2019). Gratitude and health: An updated review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–40. ↩︎

-

Boggiss, A. L., Consedine, N. S., Brenton-Peters, J. M., Hofman, P. L., & Serlachius, A. S. (2020). A systematic review of gratitude interventions: Effects on physical health and health behaviors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 135, 110165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110165 ↩︎

-

Smyth, J. M., Johnson, J. A., Auer, B. J., Lehman, E., Talamo, G., & Sciamanna, C. N. (2018). Online Positive Affect Journaling in the Improvement of Mental Distress and Well-Being in General Medical Patients With Elevated Anxiety Symptoms: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mental Health, 5(4), e11290. https://doi.org/10.2196/11290 ↩︎

-

Crawford, J., Wilhelm, K., & Proudfoot, J. (2019). Web-Based Benefit-Finding Writing for Adults with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes: Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Diabetes, 4(2), e13857. https://doi.org/10.2196/13857 ↩︎

-

Burton, C. M., & King, L. A. (2008). Effects of (very) brief writing on health: The two-minute miracle. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910707X250910 ↩︎

-

Morisano, D., Hirsh, J. B., Peterson, J. B., Pihl, R. O., & Shore, B. M. (2010). Setting, elaborating, and reflecting on personal goals improves academic performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(2), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018478 ↩︎

-

Amabile, T., & Kramer, S. (2011). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work. Harvard Business Press. ↩︎

-

Sherman, D. K. (2013). Self-Affirmation: Understanding the Effects: Self-Affirmation: Understanding the Effects. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(11), 834–845. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12072 ↩︎

-

Alt, D., & Raichel, N. (2020). Reflective journaling and metacognitive awareness: Insights from a longitudinal study in higher education. Reflective Practice, 21(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1716708 ↩︎

-

Hensley, L. C., & Munn, K. J. (2020). The power of writing about procrastination: Journaling as a tool for change. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(10), 1450–1465. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1702154 ↩︎

-

Beltz, A. M., Wright, A. G. C., Sprague, B. N., & Molenaar, P. C. M. (2016). Bridging the Nomothetic and Idiographic Approaches to the Analysis of Clinical Data. Assessment, 23(4), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116648209 ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.