POSTS

Happiness in the lab, part 5: Kindness

by Luis P. Prieto, - 17 minutes read - 3425 wordsEven if you feel that your research contributes to a bigger purpose, even if you work at it with great engagement, even if you’re resilient to setbacks and misfortune… still your time working in research can suck. This week I look at the final missing piece in our search for a happier (research) workplace: the quality of our social interactions with others. Particularly, how positive connections and prosocial behaviors can help us thrive at work (not just survive). In this post, I examine some of the main components of a prosocial workplace, how to assess them for yourself, and a few research-backed practices to make your lab a kinder place.

Throughout my professional and academic life, I have worked for extended periods of time in 5-10 different places or teams, depending on how you count. And, throughout these 20 years, I have noticed something: my happiness working at those places seems very correlated with a difficult-to-define “sense of social cohesion” or “friendliness” of the team working there. This is admittedly a small sample, and there are many cultural factors that could explain why I seem to appreciate such atmosphere (Spanish culture, in which I was born, is rather social and gregarious). But, is it really just me? Have you ever done research happily in a place where this general sense of friendliness and social cohesion was totally absent? (if so, let me know in the comments section below!).

As I finish reading and learning about positive organizational psychology to find what might make us happy in our research workplaces, I have come across research that may support the inter-cultural existence of this trend I had observed. Unlike many of the other ideas and practices about purpose, engagement and resilience (which place a lot of importance on you, the individual, and your personal values, feelings and actions), this one is about our interactions with others at work, and the team atmosphere that is generated in the process.

K is for Kindness

Kindness is the fourth pillar in “The Foundations of Happiness at Work”. A quick visit to the Wikipedia will tell us that it is “a behavior marked by ethical characteristics, a pleasant disposition, and concern and consideration for others”. However, in the UC Berkeley course they use this word as an umbrella term for a variety of prosocial behaviors, including:

- Generosity. Although in many cultures (especially Western, English-speaking ones) self-defense and competition seem like a more natural attitude when being at work, there is an increasing amount of evidence across cultures that being generous in your work interactions not only breeds a better team atmosphere, but also feels good to the individual (unless the other side treats you badly in return). One can, for instance, refer to Adam Grant’s research on “givers vs. takers”1: Basically, his research found out that it is “givers” (those people who contribute to others without expecting anything in return) who are more likely to be successful than both “takers” (those who strive to get as much as possible from others) and “matchers” (those that try to break even in work transactions). While this can make intuitive sense (we like good people rising to the top, and we’d prefer them as bosses), this runs against the popular belief that ruthless back-stabbing is the only way to climb the corporate (or university) ladder. A related prosocial behavior is gratitude (basically, thanking people for what they do for us, big and small). Gratitude has been shown repeatedly to help with job satisfaction and wellbeing2, both in workplaces3 and in research environments (e.g., to improve Ph.D. student-supervisor relationships4).

- Friendliness. Developing friendships with our co-workers is also a behavior that varies a lot from culture to culture (in some countries like the USA, choosing to go on holidays with your workmates is very rare, while in others like Poland or India it is more common). In any case, there are indications that having such work friendships is related to engagement, job satisfaction and productivity5. Some researchers argue that it is not the friendships themselves that help, but rather things like vulnerability, authenticity, compassion… which can be cultivated to make the workplace “feel friendly”, even if real personal friendships are not present. Work friendships can, of course, also backfire when work conflicts arise (as they inevitably do), leading to negative work outcomes5.

- Civility and respect. When we talk about a civilized behavior, we often refer to politeness or courtesy, but this concept also encompasses behaviors like being open to others, being humble, or interested and engaged with what they say or do. All these are closely related with respecting others and their contributions. Being civil is essential not only in customer-facing jobs like the hospitality industry, but also in any other workplace. In general, feeling respected activates the areas of our brain related to safety (i.e., we feel more “at home”), and generally increases our happiness6. In turn, being respectful has been shown to improve the image that others have of us, improve our social ties at work, and a long et cetera. An even bigger amount of research has been done on their ugly flip side: incivility. Incivility has been defined as “low intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target”7, and it is known to quickly disrupt the atmosphere and productivity of people at work, not only when they experience such incivility by others, but also by merely witnessing it being inflicted upon others, or instigating it themselves8. Detecting a “bad apple” at work (I think the technical term is an asshole) is relatively easy: you feel deflated, low in energy and self-esteem after talking to them; they normally target lower-rank people, and do it consistently. Stay clear from them… and don’t be one yourself!

- Empathy and compassion. Empathy is about feeling (emotional empathy) or understanding (cognitive empathy) how other people feel. When you empathize with someone, normally you listen to them, make eye contact, and very often you even mirror their posture or paraphrase what they’re saying in your own words. Compassion (sometimes known as active empathy) goes a step further and joins the empathy for others with an impulse to actively help or support the other person. While empathy can have positive and negative sides (especially when we feel others’ pain but feel incapable of helping), compassion has been linked to many positive outcomes like better health, stronger social interactions, more happiness, lower stress and lower turnover intentions (i.e., intending to quit)9.

Diagnose: Measuring kindness in your research workplace

As you can see, there is a lot to unpack there in the last term of the P.E.R.K. acronym. Yet, probably you can think about your everyday research work and start having an intuition of whether you work in a “kind” place: are people there (including you!) generous with their time or effort? are they friendly (or at least vulnerable and authentic), respectful or compassionate? If you want to have more exhaustive measurements of the different kindness dimensions, you can try the following research-backed instruments:

- To test yourself for generosity, you can take the “giver vs. taker” test, offered at Adam Grant’s website.

- To explore the extent to which you feel your research environment encourages friendship, you can try the “Friendships at work” test, based on Carolyn Dickie’s research on workplace friendships5.

- There are multiple questionnaires or scales that you can use to measure civility (or incivility) in your workplace. Some of the most common ones include the Workplace Incivility Scale (WIS)10, based on seminal work on incivility by L.M. Cortina, or the “Civility Norms Questionnaire-Brief” (CNQ-B, which, as its name implies, is very short)11.

- If you want to diagnose your lab’s culture in terms of compassion, you can take the “compassionate organizations” quiz, offered by the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley.

Act: Practices for a kind research environment

The fact that kindness in the workplace is such a complex topic, also has a bright side: there are many fronts on which you can try to tackle it and make things better. Hopefully, the instruments in the previous section have given you some ideas about what are the areas of kindness that need most working on (for yourself, and in your environment). Here are a few of the simpler practices I have come across for doing precisely that:

- Boost your generosity with simple practices, like:

- Doing a “five-minute favor”: once a week, pick somebody who you have not contacted for a long time, and see if you can help them in small ways. You can also put them in contact with somebody they don’t know, with whom they share uncommon commonalities (e.g., they are interested in the same kind of research questions, they are both into Russian expressionist paintings, whatever). You can also help others feel more generous by seeking help more often, in the form of such five-minute favors: asking small, low-effort favors from others that will really help you, and let them know how they helped you (see the gratitude tips below).

- Starting a reciprocity ring in your lab or department: this is a simple but powerful group event in which every participant makes requests (something they want or need but can’t get on their own), and put them on a flipchart or a post-it. Then, everyone helps fulfill them, using their knowledge, resources or social connections (e.g., just writing their name or a tip beside the request). The main idea is to lower the barrier of seeking help, so it doesn’t feel so awkward (since everybody has to ask for something). Indeed, the main obstacle to people being more generous often is that we don’t know what others need. Also, since you’re not making the ask directly to anyone, you don’t worry as much about getting rejected12. This kind of events can also help with “generosity burnout” (in which certain people always help others, but never ask for help – and eventually burn out). Plus, you will get to know your labmates better! (good for the “friendliness” side of kindness).

- Practice gratitude. A few ways you do it more, and do it better:

- Make a point of being better at thanking other people: it starts by training yourself to stop and notice more often when other people do things for you (we are often so busy that we don’t even notice, much less thank others). Then, not only say “thank you”: 1) be specific about what exactly you are thanking them for, 2) acknowledge their effort, and 3) describe how exactly their actions helped you.

- One gratitude practice that takes place sometimes in our department, is to create (and publicly announce) a sort of gratitude box in which people can anonymously put gratitude notes for specific colleagues. After some set time (e.g., a few days), open the box and deliver the notes to the person they were addressed to. I can say from experience that it feels really warm to receive these anonymous notes acknowledging you for everyday stuff you do which you thought had gone unnoticed.

- There are plenty of other gratitude practices, ranging from very simple (e.g., keeping a gratitude journal, in which you write down periodically specific things you are grateful for) to quite elaborate (e.g., writing a gratitude letter and delivering it personally to the person you’re grateful to). Many of these practices have been shown to boost wellbeing in general, and positive affect (i.e., emotions) in particular13. There are even websites or services to help you setup and keep at doing such “gratitude challenges”.

- Handle conflicts with grace. Sometimes, during your research you inevitably clash with other people, maybe because both of you need access to a limited resource, or you have strong disagreements about the path to take. These can quickly turn into incivil argue-fests, unless we are very careful. You can practice:

- Getting better at everyday peacemaking in those conflicting situations: just trying consciously to be polite, bringing levity and humor to the situation, or being modest, can go a long way towards defusing conflicts early on.

- If it is you who made a mistake or acted unethically, make a point of apologizing effectively: take responsibility for what you did, recognize the harm you’ve caused, and express (honestly!) remorse and commitment to not repeat the behavior.

- If, on the contrary, it is others who wronged you, make an effort to forgive them. You can try using structures like the REACH model for forgiveness: Face the fact that you have been hurt (Recall), visualize the other person, what you would say to them, and then put yourself in their shoes and what you would say in their situation (Empathize); think back to a situation when others forgave you and give your wrongdoer the same gift of forgiveness, unselfishly (Altruistic gift). After doing so, write down a simple note to yourself stating this forgiveness (Commit), and go back and re-read that note whenever you doubt you really forgave them (Hold on to it). Interventions based on these models have been shown to help with depression, anxiety, and hope14.

- Improve civility in your lab by using more powerless communication15: acknowledge your weaknesses, listen more (you learn when you listen, not when you speak!), talk more tentatively, or even commit to speak less in meetings16. In your interactions with others, seek advice, not self-promote. Rather than advocate (“I need you to do this”), inquire, ask questions (“what would you do in my situation?").

- Improve your workplace’s kindness and prosocial behavior through reminders of our common humanity.

- This can be done with simple cues in our work spaces: having a common area for informal interactions, with snacks or drinks; putting in your office imagery, art, plants, photos of family, banners with prosocial messages or keywords.

- You can also do explicit exercises to notice which objects around you in the office are related to social connectedness, or evoke a positive social connection… and then propose new objects that could be placed in the empty spaces17. You can also rearrange the place’s furniture to be more conducive to social interaction.

- Work on your compassion, both individually and with others:

- Probably one of the simplest and most ancient practices to boost compassion, which you can do on your own, is to try “loving-kindness meditation” (also called Metta meditation, in the Buddhist tradition). Although there are many variants of this, the basic principle is the same: picturing other people (a loved one, some neutral person, our “enemies”, or oneself), and repeatedly wishing them well. Yep, that simple (but surprisingly effective to get out of “fight or flight” mode). You can also try this longer, related “compassion meditation”.

- If you know that somebody in your lab is having some problem or going through a rough patch, coordinate with others to do something compassionate for them, to brainstorm potential ways to help this person, and actually doing it together. This will not only help the person in need, it will also create stronger bonds among the group.

Over to you

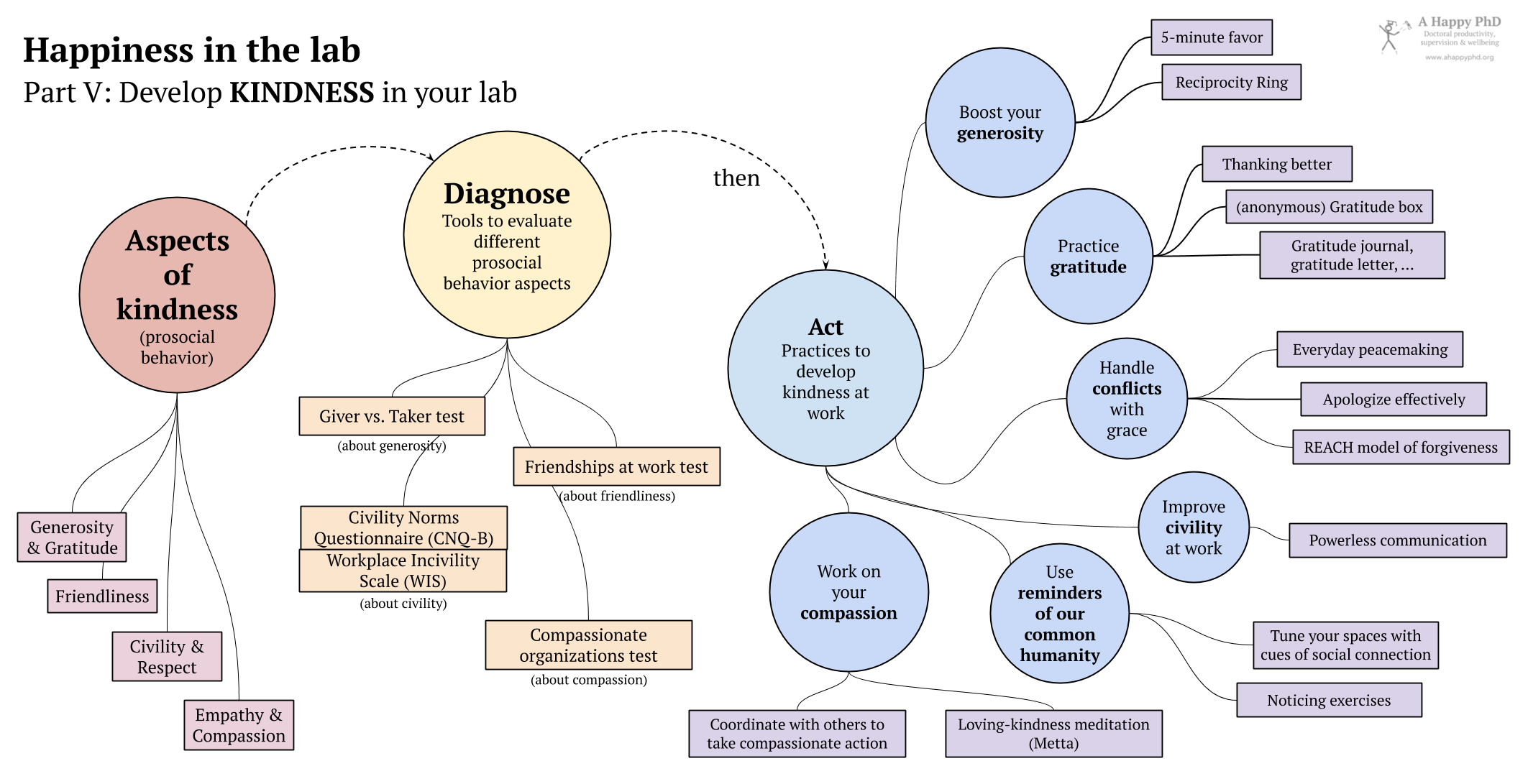

Wow, that was a long post there, but I hope some parts of it were useful (see below for a graphical summary of the main ideas and tools I proposed):

As you can see, there is plenty that can go wrong in our interactions with others when we are in the lab, doing our research: incivility, involuntary mistakes, conflict… but also there are many ways in which we can make our work places kinder and warmer. Personally, I have always been a bit skeptical of these fluffy, squishy words like compassion or generosity or gratitude. However, the more direct experience I have with these practices (e.g., I have sent gratitude letters within the past few weeks, and I try to do some compassion meditation regularly), the more I appreciate their value. An even greater value lies in not keeping these to yourself, but rather talking about them with your colleagues, and changing some of your behaviors as a group (although this requires trust with your labmates, which can vary a lot from place to place – I find quite difficult myself!).

Just try some. At your own pace.

Baby steps :)

Do you find that you work in a kind, or unkind research institution or team? Do you find these practices helpful? Do you have other tips or tricks that you use to make your lab a kinder place? Let me know in the comments below!

-

Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and take: A revolutionary approach to success. Penguin. See also the TED talk on the same topic. ↩︎

-

Davis, D. E., Choe, E., Meyers, J., Wade, N., Varjas, K., Gifford, A., … others. (2016). Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 20. ↩︎

-

See, e.g., Waters, L. (2012). Predicting job satisfaction: Contributions of individual gratitude and institutionalized gratitude. Psychology, 3(12), 1174. ↩︎

-

Howells, K., Stafford, K., Guijt, R., & Breadmore, M. (2017). The role of gratitude in enhancing the relationship between doctoral research students and their supervisors. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(6), 621–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1273212 ↩︎

-

Dickie, C. (2009). Exploring Workplace Friendships in Business: Cultural Variations of Employee Behaviour. Research & Practice in Human Resource Management, 17(1). Available online here. ↩︎

-

Di Fabio, A., Giannini, M., Loscalzo, Y., Palazzeschi, L., Bucci, O., Guazzini, A., & Gori, A. (2016). The challenge of fostering healthy organizations: An empirical study on the role of workplace relational civility in acceptance of change and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1748. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01748 ↩︎

-

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. ↩︎

-

Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, S57–S88. Available online here. ↩︎

-

Lilius, J. M., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Kanov, J., Frost, P. J., Maitlis, S., & others. (2003). What good is compassion at work. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Michigan. Retrieved from here. ↩︎

-

To fill in the questionnaire, go to page 22-23 of this PDF, and answer the 12 questions there on a scale of 1 (never), 2 (once or twice), 3 (sometimes), 4 (often) or 5 (many times), and then average all answers. In this case, higher values denote higher degrees of incivility (i.e., bad!). The full reference is: Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Leskinen, E. A., Huerta, M., & Magley, V. J. (2013). Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: Evidence and impact. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1579–1605. ↩︎

-

Go to page 39 of this PDF, and answer the four items there using a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The average of your responses, out of 7, will give you a notion of how civil your workplace is. The full reference is Walsh, B. M., Magley, V. J., Reeves, D. W., Davies-Schrils, K. A., Marmet, M. D., & Gallus, J. A. (2012). Assessing workgroup norms for civility: The development of the Civility Norms Questionnaire-Brief. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(4), 407–420. ↩︎

-

Reciprocity rings are often run periodically (e.g., once a week) and can be as brief as 20 minutes. Adam Grant has a whole business and technology (probably paid) based on this practice, for companies, but you can try this basic idea on your own as well. ↩︎

-

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.377 ↩︎

-

Wade, N. G., Hoyt, W. T., Kidwell, J. E., & Worthington Jr, E. L. (2014). Efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions to promote forgiveness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(1), 154. Available online. ↩︎

-

Grant, A. M. (2013). Give and take: A revolutionary approach to success. Penguin. ↩︎

-

Don’t do this if you already find yourself normally staying silent for most of the meetings! Ask around among your colleagues, whether they think you speak too much or too little in meetings. Sometimes it is the others (e.g., your supervisors, or more outgoing colleagues) who should exercise powerless communication more than you. ↩︎

-

NB: There is a limit to this practice as well, since too many such objects will create visual clutter, and you may end up not really being able to notice these objects (and the positive connection they evoke) separately. But if your spaces feel too empty and clinical, this is definitely worth a try. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.