POSTS

Choosing not to drop out: a view from self-determination theory

by Luis P. Prieto, - 18 minutes read - 3697 wordsIn last week’s post, we established that dropping out of a Ph.D. (or thinking about it) is surprisingly common, and we saw demographic and socio-economic factors that seem related to doctoral attrition. In this post, I dive into another strand of research that relates doctoral dropout with a general theory of human motivation: self-determination theory. This research helps explain why you may persist and finish your doctorate (and even have fun doing it), despite having such socio-economic factors playing against you. Or vice-versa. The post also gleans practical advice from the literature on doctoral attrition, in the hope of helping students and supervisors avoid this common pitfall.

Last week, I left you with a surprising realization of mine: despite having several of the most common factors of doctoral attrition against me, I finished my Ph.D., and actually enjoyed most of that trip. How come?

There is one thing I noticed in many of the studies I mentioned last week: studies asking to students about dropping out often mention the importance of supervision style (or the relationship with the supervisor); and studies asking supervsiors often highlighted whether students are prepared (or, in a sense, “good enough”) to face the hardships of a Ph.D. Even if nobody in these studies is directly saying: “it’s the other side’s fault”, it gave a bit the impression of a certain “us vs. them” mentality, a sort of blame game.

Whose fault is it, then? students or supervisors? The answer probably is “it depends”, but I have now come to believe that this is a false dichotomy. The point is not whose fault it is, but rather what elements have to be there for a student to engage in the research work, persist, and eventually finish the Ph.D.

A way out of the blame game? Self-determination theory

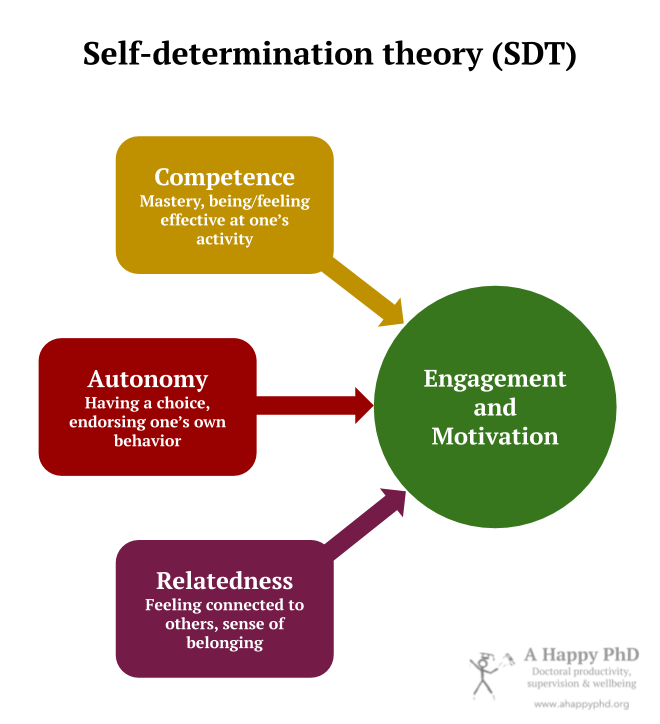

As I was reading for last week’s post, I found another big group of recent studies, which looked at the problem from a different perspective: self-determination theory (SDT). SDT is a general theory of human motivation that proposes that all human beings have a need to be competent, autonomous and related to others1. The idea is that people feel intrinsically motivated and satisfied when doing an activity that meets these needs – and feel “controlled” or “amotivated” when the activity does not. Hence, these studies look at the problem of students dropping out in the sense of how the Ph.D. process and their environments meet (or fail to cater for) these needs – something that is not the sole responsibility of the student, nor the advisor, but rather the interplay between both2. How does this theory of motivation help explain doctoral dropout and persistence?

Insights from SDT studies of doctoral dropout

It is worth noting that many of these studies had smaller sample sizes, and often were more qualitative, asking about people’s feelings and motivations. Thus, they may not be directly generalizable to you or your particular situation. Still, they unearthed several interesting insights and themes:

- Feeling competent and the “impostor syndrome”. One of the themes that has appeared most often in relation to people dropping out or succeeding in the Ph.D., is how competent students felt (about doing research in general, and the different skills the doctorate entails). It appears under different names: “perceived competence”3, “self-efficacy”4… or their negative flip side, the “impostor syndrome"2. Basically, it seems that a lot of student success and persistence hinges on finding ways to shake off this (totally inaccurate) impression that everyone else “gets it” and knows how to do stuff – except you. A Ph.D. involves a lot of new skills and knowledge (from writing in a totally different style, to reading information and critically assessing it, being systematic and methodical, being able to abstract and synthesize, or particular technical skills). Thus, if you (and your advisors) manage to find ways of progressively developing those skills, practicing and practicing, first in smaller/easier projects and then increasing difficulty and responsibility, normalizing failure and learning from it, and highlighting and recognizing successes, you will in the end feel that you know how to do stuff (not everything, and not equally well, but much more than at the beginning), and you will believe that you could learn other things if you need it (which is true). When you have this continuous feeling of being “competent enough”, persisting and finally closing the Ph.D. seems to be much easier.

- A sense of progress. This theme goes hand in hand with competence as well. What do we use to determine if we are (or we feel) competent? Feedback. A rejected paper, an interested audience when you speak at a conference, looking at the data and finding that your hypothesis was confirmed, or finding that there is some error in the data and you need to repeat the experiment… all those are forms of feedback that shape our perception of how competent we are, and whether we are reaching our goal of finishing the Ph.D. The problem is, many of the processes involved in a Ph.D. (like preparing and running and experiment, and then analyzing the data and getting some results; writing and publishing a paper; etc.) are very long, and the scarcity of feedback can breed an insidious sense of uncertainty. Am I closer to the Ph.D. now than two months ago? Because, our fears argue, if I’m not advancing, I might as well quit and spend my time on something else. The vagueness of criteria for obtaining a Ph.D. does not help either (what counts as a “substantial scientific contribution”?). Thus, some studies have found that having a feeling of progress, of advancing, is essential to persist in the Ph.D.5. This study also suggests that we tend to evaluate progress on a daily basis (“did I do something useful today?"). How to make this progress visible on an everyday basis is a thorny issue for which I have not seen a good, general solution. However, knowing that this is important, you can try to make your progress more tangible in every project or long-term task (see, for example, the paper writing process I propose, which emphasizes more frequent feedback from co-authors and editors than many people normally use). I will dedicate an entire post to dig deeper into this fostering of an everyday sense of progress. Similarly, finding whether students are feeling “blocked” in their progress for a long time, and seeing if something can be done to help them unblock themselves, seems a worthy goal for doctoral supervisors 6.

- Not too much distress. This one is quite obvious, but still worth pointing out: no matter how competent you feel, how much self-discipline you have, or how much progress you make, if doing your Ph.D. only brings you negative emotions, if it continuously feels like a burden, that it is full of problems (be them research-related, economic or personal, or psychological)… it is only a matter of time for you to consider quitting. It basically goes against our sense of autonomy to do something that feels bad, again and again. Some of these studies found that, even if everyone experienced bad episodes at one point or another, doctoral students that completed the Ph.D. had experienced less negative emotions and that those were counter-balanced with positive ones5. Thus, we should not neglect our daily, “experiencing self”7: if getting up in the morning feels like a drag, if the idea of doing research or meeting your advisors fills you with anxiety, pay attention. Why is that? Talk it over with colleagues, friends, family (because you are not alone8). And conversely, do not ignore the little triumphs, the activities or parts of your day when you feel exhilarated, curious, in “the zone”. In a later post I will dive into some of this research on how to be non-judgmentally aware of the negative moments, and to emphasize or savour the positive emotions we all have in our everyday research life.

- Social support. Similar to what we saw when talking about anxiety and depression, it seems that strong social ties may help you complete the Ph.D.. Not only is loneliness linked to doctoral attrition2; this need for social support to endure hard times may also explain the emphasis that many of the studies on attrition make on the quality of the student-advisor relationship. After all, for many Ph.D. students, the supervisor is the only person they interact with in relation to their doctoral research. Hence, if bad times come and no support is given from the main staple of socialization (or worse, if the advisor relationship is actively disruptive), a doctoral project can go south quickly. And this may also be the reason why the presence of additional social support factors, like the positive departmental and scientific community interactions or integration practices, seem protective against doctoral attrition9,10. Probably it is a good idea to seek (and point out to your students, if you are an advisor) these additional situations and people that can provide useful research-related feedback and support: summer schools, doctoral consortia, local Ph.D. support groups… all can help students realize that their problems are not unique, that difficulties do not mean necessarily that there is something wrong with them or their project. Both students and supervisors should take care of the student-supervisor relationship. Don’t let it go sour!

- A project that makes sense. Having a sense of purpose, being able to work on a project that makes sense to you (versus having no clear research project or being forced to work in a direction that does not make sense to you) also appeared as differential between students that completed or dropped out of the Ph.D.5. This can take many forms: having an idea of “where you’re going” with your doctoral research, and having some sort of plan (even if it is a vague one at the beginning, or it changes later on)11. Again, this goes with the need for autonomy: the project has to make sense to you (no matter how much sense your advisors see in it). If you don’t feel a sense of ownership, that this is your project, then it is less likely that you will plough through the hard times to complete it. This “making sense” can also manifest in whether you associate the research, your project, with feelings of interest, curiosity, and pleasure. Another way to find purpose in your project is if you perceive that it is useful (for you, or for others, or for the advancement of human knowledge). This overall theme has direct applications for supervisors: forcing a student to take a direction without checking whether it “makes sense” or feels interesting or useful for the student, can have dire consequences. And, from the student perspective, similar advice can be given: if you find that, for a long time, the whole idea and direction of the research do not make sense to you, speak with your supervisor, and with other fellow researchers, about that. I cannot stress the importance of this sense-making enough: it is very, very important, as SDT researchers talk about autonomy as the “linchpin of motivation”2, meaning: no matter if you get social support and you feel competent – if your research does not make sense to you, if it does not feel like “your baby”, engagement with your Ph.D. will likely falter. Ignore this feeling of absurdity at your own peril!

Practical advice from the attrition literature

All this research and abstract notions of “social support”, “competence”, or “progress” are very nice but… does any of these studies actually tell us what exactly we should do (as students, or as advisors)? are there any practices or actions that have been shown to work consistently to help students persist in their Ph.D.?

It seems that the research about practices and interventions to avoid doctoral attrition is not as developed as other areas of the problem. The research on SDT and attrition does have some general advice, based on what they call “basic needs theory” (BNT): basically, the idea that, to be intrinsically motivated and engaged in an activity, the environment should provide certain particular types of support to the three SDT needs (competence, autonomy and relatedness). Thus, based on BNT, some researchers propose12,13:

- To support competence, the environment has to provide some forms of structure: defining clear objectives, providing constructive feedback or advice on technical skills or planning out the students’ career, and having space for discussions about the difficulties being faced by the student at the moment, and potential solutions.

- To support relatedness, researchers suggest to foster the advisor (and other actor’s) involvement: having a warm, respectful relationship when talking about research, reassuring the student when needed, and being concerned about the student not only as a researcher, but also as an individual human being.

- Finally, to support autonomy (which, let’s remember, was the most important of the three), the environment can help mainly by providing choice and enabling curiosity-based explorations. This includes giving students freedom in how they carry their work (e.g., work schedules or tooling), asking for their opinion about the direction of the research, encouraging them to work independently, or avoiding situations in which students are directed strongly, or under a lot of pressure (including not only psychological pressure, but also economic pressure, or even incentives, as they are known to damage intrinsic motivation sometimes)13.

Aside from such general advice, the research looking at dropouts from the point of view of SDT also includes other ideas for improving attrition rates, although their effectiveness is rather conjectural (i.e., not many are empirically tested). I have seen mentions to practices such as: journaling (as it is known to boost our “inner locus of control”, which may help with impostor syndrome), some forms of group therapy (e.g., in some universities Ph.D. students have some kind of peer support groups), or even cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)2. Other authors take a different kind of approach and suggest smaller cohorts, tougher or more detailed selection processes or probation periods, to try to get at candidates that have higher chances of completing the Ph.D.

So, what will you choose?

Coming back to the initially not-so-great chances of completing my Ph.D. when I first started it, does this research based on SDT help explain why I finished the process successfully, and actually enjoyed most of it?14 I think it does.

As I mentioned, back when I started the Ph.D., I was single, the career prospects after the Ph.D. were unclear15, my academic credentials were not outstanding, and I had no funding or scholarship to fund my Ph.D. However, the good news was that I had a strong social network of friends and family (who were always supportive of my decision to pursue a Ph.D.), and I had been saving money so that I could support myself during this period. Furthermore, I had the luck to get great supervisors. That alone helped tremendously. Some of the things I think they/we did correctly, in light of what I have now discovered about SDT, include:

- My Ph.D. project’s direction was quite open at the beginning, which enabled curiosity-based explorations as I started getting familiar with the literature in my research field. Of course, some hints were given here and there by my advisors, but I did not have the impression of my direction being “externally controlled”.

- I was included in an ongoing, relatively small research project in which I collaborated with Ph.D. students from other fields, and in which we had liberty to decide how to do things, a certain degree of responsibility – but it also was a project stakes in case of failure were relatively low.

- The aforementioned low-stakes project/collaboration consisted mainly of a long field study in a school (including a lot of classroom observation). This gave me a first-hand experience with the setting and people that my research should be benefitting, and made me aware of problems that my research contribution (still undefined at the beginning) could try to solve. This was invaluable later on to feel that my project “made sense”, and that it could be useful to somebody.

- My advisors put a lot of emphasis on planning and making sense of the Ph.D. research direction, through iterative plans for next steps and future studies, and the use of the CQOCE diagram as a kind of “compass” to understand where I was going.

- These diagrams and plans (of which I did twenty-odd versions during the Ph.D.), as well as the expectation of having periodic written reports about my advances, helped provide constant proof of my progress during the Ph.D. process.

- This feeling of progress was also reinforced by having regular meetings with my supervisors (once every two weeks, approximately). In these meetings, supervisors provided hints, ideas, constructive feedback, but never solutions or micro-managing instructions. The relationship with them was always good, and I could clearly feel that both my advisors cared about me not only as a human resource, but also as a person.

- Halfway through the Ph.D. process, my advisors found a way to fund my doctoral process, by re-aligning my research slightly to also address the needs of an ongoing research project of the lab. This re-adjustment was tricky from an autonomy point of view, but we managed to integrate it conceptually within the ideas and interests I had (i.e., the project still made sense to me).

The list of positive aspects goes on, but you get the idea. I think these factors helped my being intrinsically motivated to do research, to the point that much of the hard work did not feel like a burden – I was curious, and it “made sense” (for the most part). Of course, this is all in retrospect: probably back in the day I found several of these (like the lack of detailed descriptions of what I should do) confusing or irritating. In any case, I think I was extremely lucky to count with such advisors, and I recommend you think carefully and review your options before choosing a supervisor (a post on that topic will come later on).

What about you? Do you think your current research environment supports your competence, autonomy and relatedness? You can try the D-N2S questionnaire12 to find out – and talk with your supervisor and others if it doesn’t.

Update: Newer studies in this strand of research point to different kinds of doctoral student “motivational profiles”, which seem to be related to doctoral completion. You can find out more about these new studies and motivational profiles, in the next post of the series on doctoral dropout.

Give these ideas a try, and let me know how it goes in the comments section below!

-

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. ↩︎

-

Beck, M. (2016). Examining Doctoral Attrition: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. The Nebraska Educator, 3, 5–19. ↩︎

-

Litalien, D., & Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in PhD studies: A comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 218–231. ↩︎

-

Overall, N. C., Deane, K. L., & Peterson, E. R. (2011). Promoting doctoral students’ research self-efficacy: Combining academic guidance with autonomy support. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(6), 791–805. ↩︎

-

Devos, C., Boudrenghien, G., Van der Linden, N., Azzi, A., Frenay, M., Galand, B., & Klein, O. (2017). Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: a matter of sense, progress and distress. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(1), 61–77. ↩︎

-

And the basic goal of most applied psychology, it seems. See the references to Kurt Lewin in this interview with Danny Kahneman (one of the most influential psychologists alive). ↩︎

-

As opposed to our “remembering self”, which we use for decision-making, and which may be prone to different biases on how we remember our past emotional experiences. See the description of these “two selves”, in wikipedia, and in Kahneman’s (2011) own book on the subject, the very interesting Thinking, fast and slow. ↩︎

-

For instance, if you want to see quotes and descriptions from other students’ difficult times (not to depress yourself, but rather to see that yours is not a unique case because of some flaw of yours), you can take a look at section 4 (need thwarting) in Niclasse-Haenggi, C. (2018). Doctoral students’ well-being–an imperative on the path to accomplishment. Das Doktorat: Anleitung–Betreuung–Verantwortung Le Doctorat: Direction–Encadrement–Responsabilité. VSH-Bulletin, 44(3/4), 8–16. Retrieved from http://www.hsl.ethz.ch/pdfs_bull/18_VSH_Bulletin_Nov_web.pdf#page=10 ↩︎

-

Bair, C. R., & Haworth, J. G. (2004). Doctoral student attrition and persistence: A meta-synthesis of research. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 481–534). Springer. ↩︎

-

Rigler Jr, K. L., Bowlin, L. K., Sweat, K., Watts, S., & Throne, R. (2017). Agency, Socialization, and Support: A Critical Review of Doctoral Student Attrition. Paper Presented at the 3rd International Conference on Doctoral Education. Presented at the University of Central Florida. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED580853.pdf ↩︎

-

In a sense, the CQOCE diagram of your thesis that I have shared in a previous post can serve as a first signpost in setting this direction and starting to plan. ↩︎

-

Van der Linden, N., Devos, C., Boudrenghien, G., Frenay, M., Azzi, A., Klein, O., & Galand, B. (2018). Gaining insight into doctoral persistence: Development and validation of Doctorate-related Need Support and Need Satisfaction short scales. Learning and Individual Differences, 65, 100–111. ↩︎

-

Niclasse-Haenggi, C. (2018). Doctoral students’ well-being–an imperative on the path to accomplishment. Das Doktorat: Anleitung–Betreuung–Verantwortung Le Doctorat: Direction–Encadrement–Responsabilité. VSH-Bulletin, 44(3/4), 8–16. Retrieved from http://www.hsl.ethz.ch/pdfs_bull/18_VSH_Bulletin_Nov_web.pdf#page=10 ↩︎

-

Actually, that is the origin of this blog’s name. The idea of a “happy Ph.D. (student)” looks like an oxymoron to many people, but that is exactly how I felt during most of my doctorate. Now that I am an advisor myself, I’d like every Ph.D. student to have access to that kind of good experience… and this blog tries to get at what tools, practices or ideas can help you (and me) to get there. ↩︎

-

E.g., back in 2009, the financial crisis had just struck, and it was only a matter of time that academic positions in Spain would become very scarce. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.