POSTS

More effective group decision-making meetings

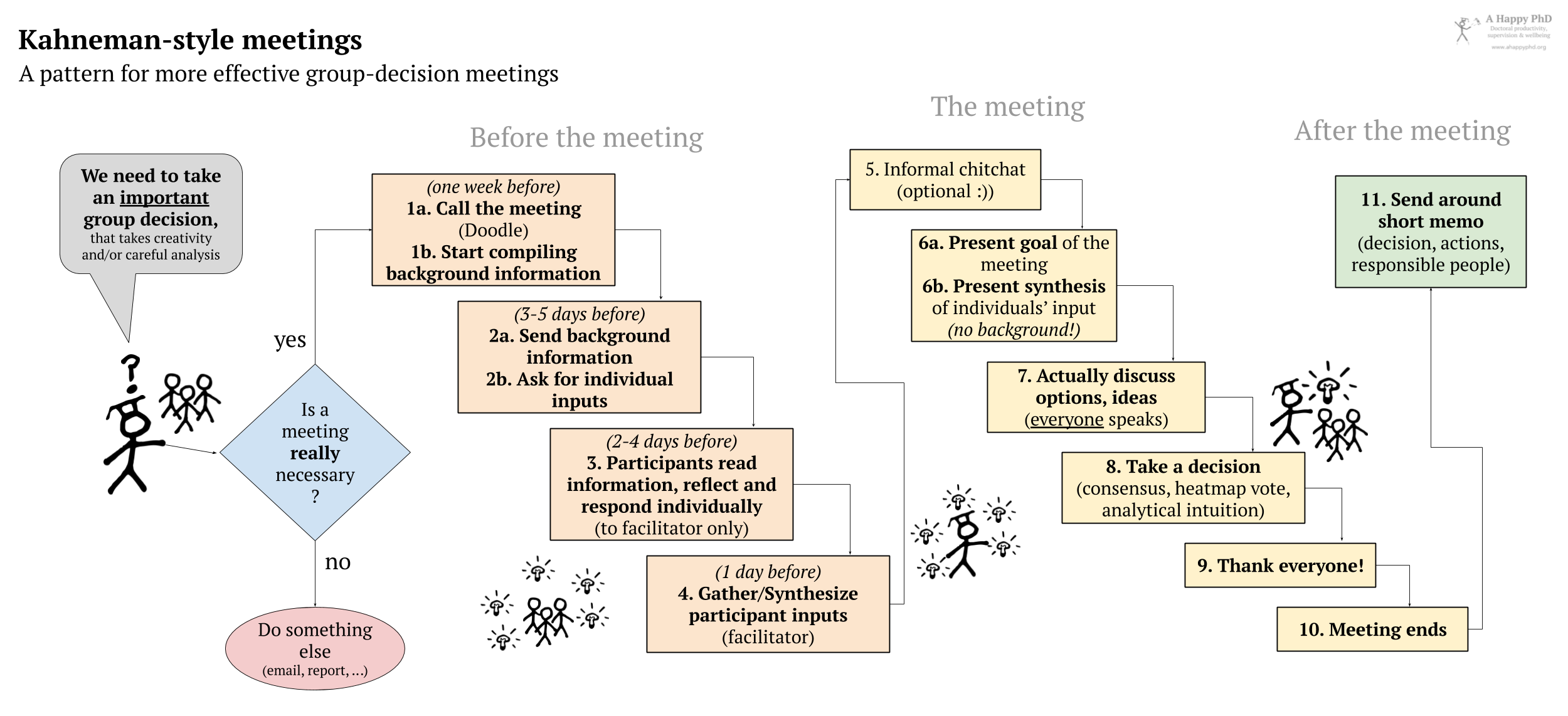

by Luis P. Prieto, - 10 minutes read - 2096 wordsHave you ever gone out of a supposedly important meeting, after more than one hour of talking, but still feeling like a poor (or obvious) decision has been made? In this post, I go over a simple pattern to organize more effective meetings when a group decision or proposal has to be made. Don’t be fooled by its simplicity: it’s much more effective than “business as usual” meetings, but people (including ourselves) will resist it fiercely, because it feels unnatural to act against our internalized meeting routines.

Meetings I hate

During my years in academia (and before that, in the industry), I have been to many, many… many meetings. Some of them were useless from start to finish, e.g., when somebody just wants to communicate something to a group of people that could have been better (and faster) said in an email or document – you know, those where everyone around the table is just doing their email or Facebook.

What a waste.

There is, however, another kind of meeting I find even more unnerving: the meetings where you really need to take a decision, or find a creative solution to a difficult dilemma… but end up with no decision whatsoever, just taking the first option that came to anyone’s mind. These meetings usually go like this:

- (0 mins into the meeting) Everybody arrives to the meeting (if we’re lucky, on time) from their previous meeting, or lecture, or task – rather absent-mindedly (their heads still battling with the unsolved problems of the previous meeting).

- (5 mins into the meeting) There is some informal chat (about recent holidays, or family, or latest news and gossip at the institution), as people ease into being among this new group of people.

- (10 mins) Slowly, the person who called the meeting or the facilitator (if we are so fortunate that one has been designated) tries to get people’s attention so that the actual meeting can start.

- (15 mins) The facilitator (or someone else) starts a slide presentation about the background information and latest events related to the decision to be made. Sometimes, multiple people have to talk about different aspects of the background of the meeting. This is often the worst-case scenario, as people start discussing whether some small detail of this background is 100% correct.

- (45 mins) Somebody notices that almost all the time allotted to the meeting has passed and nothing has been decided, so the background presentations are cut off (maybe leaving important information or options out of everyone’s mind), in order for the actual decision to be discussed.

- (50 mins) One person (usually, the one highest in the hierarchy, or the one who most likes the sound of their own voice) talks about the first option that came to their mind, for several minutes. Often, everyone else has had the same idea already, so they start (or continue) doing email. If we’re lucky, more than one option is actually spoken about.

- (sometime 60-90 mins into the meeting) Everybody has to run to their following meetings, so a rushed decision is made: an explicit decision, one would hope – but very often the decision is rather made implicitly (leading to misunderstandings or resentment) or unilaterally by the boss after the meeting ends (which makes the meeting kinda pointless). The decision probably takes the most obvious, unimaginative option that first appeared on the table. Many people have not even had the opportunity to voice their opinion or a single idea.

Sounds familiar? This happens not only in big research projects with many partners, but also in smaller labs, and even in humble PhD meetings, when there are multiple supervisors and/or additional people (be it professors, postdocs or other PhD students) that have been called to weigh in or give an expert opinion about some important aspect of the problem at hand (a practice which I actually recommend – it is not that all group meetings are bad per se!).

Yet, one cannot help but wonder: Is there a way to waste less time, or at least, to come out of the meeting after really having discussed and considered options beyond the obvious?

It turns out there is.

A more effective meeting pattern

This decision-making tip, or “pattern”1 comes from an interview with Daniel Kahneman about decision-making, which is why I sometimes call these the “Kahneman-style” meetings. I am not sure, however, that he invented it, or actually studied its effects in his own research. The problem with many group meetings, he notes, is that people converge on one idea too fast, not giving serious thought to the multiple alternatives available (or generating more options). This is what, in some circles, is called “group-think”: the fact that we tend to conform with the (apparent) opinion of a group, even if initially we had different, original ideas about the question at hand. In order to avoid such early convergence, Kahneman suggests forcing more individual work, and taking advantage of time outside the meeting. The steps of this new kind of meeting would go like this:

- (one week before the meeting) We decide that a meeting is necessary (is it really?? if there is no creative, important decision to be made, maybe a usual meeting, or an informative email, is enough). Somebody (e.g., the person calling the meeting, or whoever has most background information) starts compiling the background information that people will need to take a decision. The meeting is called, a suitable time/place is decided (e.g., via Doodle), etc. as in a normal meeting.

- (3-5 days before the meeting) An email is sent to all meeting participants, with the background information (e.g., a report, a series of papers, etc.), an explicit statement about what decision or question the meeting intends to resolve, and clear instructions to the participants: they are expected to go over the background and provide their own initial answers, ideas, options, or solutions – to be sent just to the coordinator/facilitator before the meeting (tip: set a clear deadline, e.g., no later than two days before the meeting).

- (2-4 days before the meeting) Everyone who plans to attend the meeting, looks at the material at a time of their own choosing, and reflects about the problem/question at hand. Then, according to the instructions, everyone sends a few answers/ideas/options to the facilitator only. This email does not need to be very lengthy, maybe a few bullet points will suffice – the point is to capture a wide array of ideas, not to write an essay about each idea. Of course, the facilitator (especially if it’s you, the PhD student) also generates his own set of ideas before reading others’ input – let your own voice and ideas be heard!

- (1 day before the meeting) The facilitator compiles the input received from all participants, synthesizing it into a small slide deck or a short report/handout. It is crucial that this synthesis is not very lengthy: fuse ideas that are very similar, and write just enough to get the gist of each idea. Also, leave out who proposed the idea: people will find out eventually, but try to help them judge ideas without the social dynamics and hierarchies interfering. In total, going over this synthesis should not occupy more than 5-10 minutes during the meeting.

- (0 minutes into the meeting) Everyone arrives to the meeting. There is some informal chat (about recent holidays, or family, or latest news and gossip at the institution), as people ease into being among this new group of people. (Yes, this is the only step that has not changed from the business-as-usual meetings).

- (10 mins) The facilitator quickly presents the goal of the meeting (in the form of the explicit question/problem that was sent in the preparatory email), and goes over the synthesis of proposed ideas slides created in step #4 (or gives the handouts for people to read individually in silence). Very importantly, this introduction should contain NO background information (if people have reflected and answered about the problem, just looking at the ideas proposed will probably be enough of a memory refresh; if they did not, that’s their problem). Instruct people to abstain from discussing right away: the facilitator can present the options, or let people read the options for a couple of minutes in silence, maybe just asking quick clarificatory questions if any of the ideas is not clear. This is actually very hard, staying silent in a room full of people that have come to talk… but it is necessary! remember, we are trying to delay early convergence, until we have considered all the options.

- (20 mins) The facilitator asks for any additional ideas or options that may not be in the synthesis, which may have occurred to participants in the meantime. Then, the actual discussion begins. The facilitator should try to get every person to voice their opinion (even the ones that tend to stay silent, there are always some of those in every meeting).

- (30-45 mins) At this point, probably opinions will have converged naturally into what the group thinks is the best option. If we want to force the group to consider multiple aspects or criteria for the decision (like costs, feasibility, effectiveness, etc.), we can go over all the options and rate them in every one of the important dimensions, before asking for a vote (similar to the “analytic intuition” approach I mentioned in a previous post). This vote can be by simple show of hands, or my personal favorite, the “heatmap voting”, in which every person has a number of votes (e.g., three) to be distributed among the options as they like. The results of the vote can be compulsory to be followed, or just an advisory decision (if the boss or the PhD student has the last word on what to do), but be clear about this before the vote, so that people do not feel betrayed afterwards.

- (40-55 mins) The facilitator thanks everyone for their time and creativity, and goes with the group over the next steps or tasks to be taken in executing the decision, and who is responsible for each.

- (45-60 mins) The meeting ends. Everybody leaves with the satisfaction of a job well done, and even with some minutes left to chat a bit more, grab a coffee or do some stretches, before the next meeting or task begins.

- (After the meeting, ideally the same day) The facilitator (or another designated person) sends all participants a short memo with the decision taken by the group (or by the ultimate decision-maker), the next steps (with deadlines) and their assignment to the responsible people.

That’s it. You can see a graphical summary of the method below.

As you may have noticed, this method has a few additional steps, and requires some preparation before the meeting, by everyone involved (and especially the facilitator, which may be you). Hence, I would not use it for every single meeting, just those that are important and require careful consideration and/or creative solutions by a group of people. But, if the topic at hand is not important, why meet at all? Personally, I have used this method several times in the past months to take decisions about an international research collaboration we have, and every time it has worked well: we came out of the meeting in record time, with a decision taken, and the meetings themselves were lively and engaging for everyone.

There will be resistance. Heck, probably you yourself will resist doing this, as it has several awkward moments (asking people to send ideas only to you, or staying silent in a room full of people). Resist the urge to go back to your old ways.

It is worth it.

It may take a few runs for people to understand that this method is really more effective, engaging and participatory. But eventually, most people see that the benefits (being engaged and seeing your opinions considered, rather than doing email during long, pointless discussions) outweigh the costs (reading the background information whenever you feel like it, and writing down a few bullet points).

Did you try this meeting pattern? How did it work out? Do you have other “meeting hacks” you want to share? Tell us about them in the comments section below!

Header image by Innovation Lab.

-

Here, pattern is meant in the sense of “a reusable solution to a recurrent problem”, an idea championed and developed in the field of architecture by Christopher Alexander. See Alexander, C. (1977). A pattern language: Towns, buildings, construction. Oxford university press. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.