POSTS

Monday Mantra: On scientific communication and research in general

by Luis P. Prieto, - 5 minutes read - 974 wordsWhen we present our research to others, in a conference or in writing, we often feel insecure: is what I found obvious? is there a fatal flaw in my reasoning or my data analysis? will the audience finally unmask me as the impostor I am? This week’s short “Monday Mantra” goes at the heart of such unproductive self-talk. What is all this really about?

I am finally back from a couple of weeks of scientific conferences and visits to other labs. The physical tiredness of the trip (despite my efforts to pace myself) is more than compensated by the excitement of hearing about interesting new ideas, new methodologies to apply, contacts for future collaboration, and a big pile of references to new research I want to read. However, one also brings back the memory of quite a few unsuccessful attempts at scientific communication (be it boring talks or abstruse papers).

This got me thinking about scientific communication. Despite all our good will (no one tries to be boring on purpose), our foibles often trip us up when we try to tell others about our research. We mumble away when asked about our current research, we undercut our findings’ interest in front of the famous professor or, worse, we try to make slides that are over-complex or full of formulas, to show “we can do math”.

I believe that, behind many of these failed attempts at scientific communication, are different insecurities, impostor syndromes and other related flavours of unproductive self-talk. We feel inadequate, judged by our audience, confronted with them like they’re the enemy. The best advice I’ve heard regarding this kind of situation (from different people and in slightly different forms), is this:

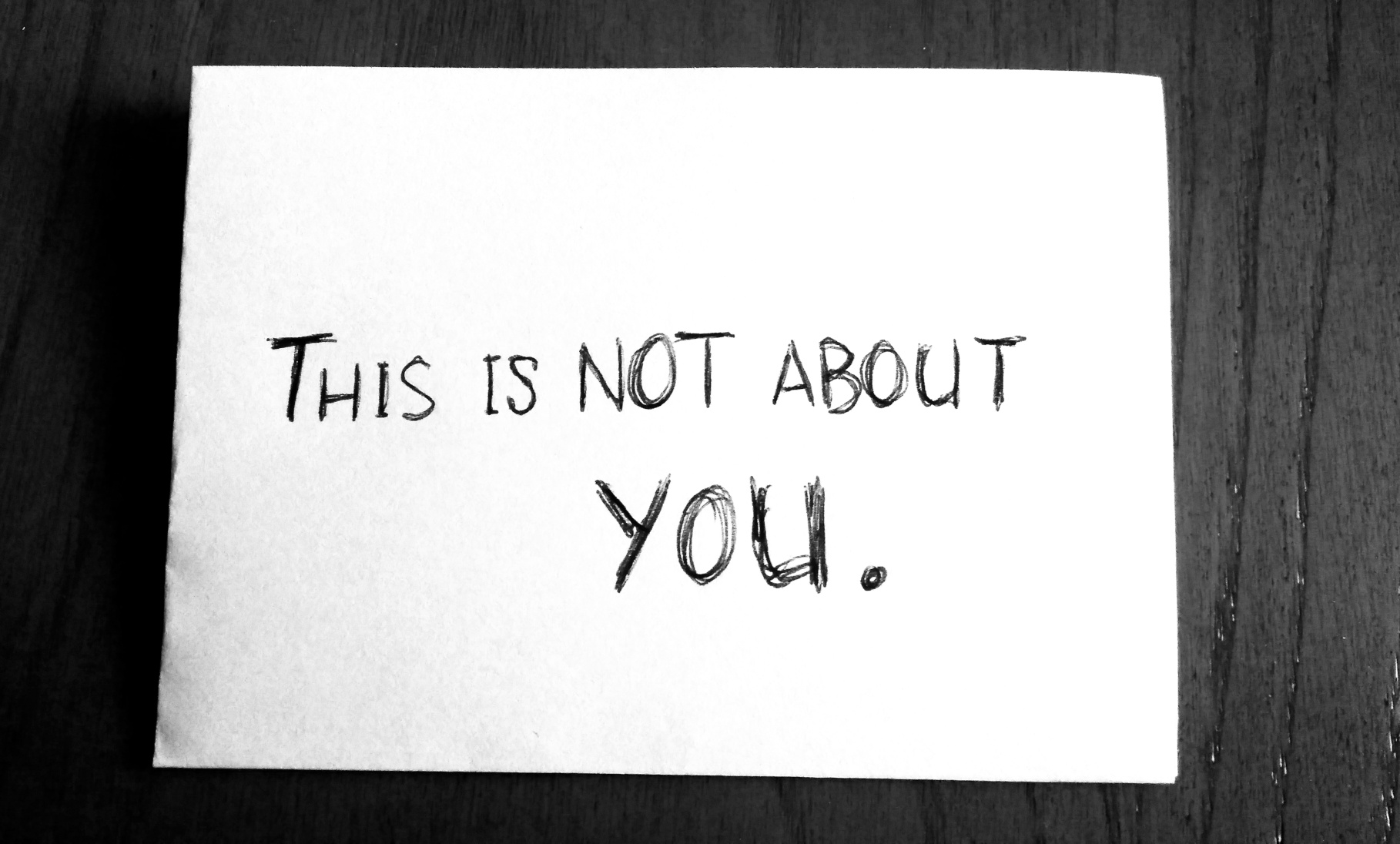

“This is not about you”

Yes. That’s it.

Despite what your ego might let you think, the presentation, the slides, the pitch… none of this is about you. It is about the work. The findings. The new knowledge that you found and the evidence that supports your claim. Nobody is there to judge you particularly. They probably don’t even know who you are. But they care about these new ideas you present. They are curious, like you. They want to learn.

Don’t get me wrong: we are all self-referential. We are the protagonist of most of our thoughts because… well, we are the protagonist of everything that happens around us, it seems. This is all natural. However, when such self-referential patterns of thought (i.e., about me, myself an mine) get out of control, we get into trouble. Self-referential thought patterns and rumination have been repeatedly linked with depression and social anxiety disorder (those feelings of inadequacy in situations where we present ourselves in front of others). Having a lot of comparative thoughts (are we less smart than others? is our work worse than others’?) has also been linked with depression1.

In general, many of the ugly episodes in the otherwise placid academic life, happen when people make the research be about them personally, not about the knowledge: the battle of egos between two prestigious professors, the “asshole supervisor” that exploits students for his own benefit, the obsession with publication and citation metrics…

Conversely, if you look at great scientific communicators, those inspiring researchers that leave you wanting to dedicate the rest of your life to their topic, seem to have an opposite focus:

- They believe (and make you believe) that their topic or research problem is incredibly interesting

- They focus on how their new findings can be made digestible by others, connected with their experience and knowledge

- They make clear how the new knowledge (note: not themselves) can be useful for others

- They make sure you understand to what extent their findings are reliable (or what weaknesses or alternative explanations are there)

- They provoke audiences to interact with their ideas (rather than trying to crush them with their superior knowledge)

The next time you are present in a very good scientific talk, try to notice whether the speaker makes it about them, or about the work. Chances are it will be the latter. Also, notice how you hear the talk: are you really interested in the speaker? or are you rather there to hear about interesting new findings?

Do you have some scientific communication tasks to do this week? Try it out. If you read my previous post about the Monday Mantras, you know the drill: take a paper card or post-it, write the mantra on it, put it on your nightstand or somewhere you will see it, carry it around with you, put it very visible, and reflect shortly about it before you prepare your communication work. See if it makes a difference.

Did you find this short prompt helpful when thinking about your scientific communication tasks? Do you have other mantras that help you when writing your papers or preparing your presentations? Let me know in the comments below!

A little housekeeping – Summer break!

I am taking a few weeks of “blogging break”, to pile up new topics, read background research and strategize a bit what will come in the new season of A Happy PhD. Since most of the readership of this blog seems to be in the North Hemisphere, probably people will appreciate the new contents being held back until your comeback from a well-deserved summer break. Because you are taking a break this summer, right?

Do you have ideas for new topics or things I could do differently? Let me know in the comments below. So far, it’s been a great learning journey for me, I hope you had half as much fun learning about these things as I did!

-

… which seems to be the reason why many recent studies see a correlation between Facebook and other social network usage, and depression. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.