POSTS

PhD tool: Pitching your research with the NABC model

by Luis P. Prieto, - 9 minutes read - 1860 wordsAs a Ph.D. student, you very often have to present what your research is about. Maybe you want to get quick feedback from a visiting professor. Or you need to give a talk at a conference or doctoral consortium. In this post, I go over a technique adapted from a large US research lab I once visited. I will walk you through its simple four- (or five-)part structure, including real examples from my own work. Don’t be fooled by its simplicity… simplicity is actually its main strength!

As the summer gets close, many of my Ph.D. students (and I as well) get ready to go to conferences, or workshops, or visit other labs. In all those situations, there will come a moment that I personally dreaded for a long time: when somebody asks you “what is your research/paper/thesis about?”. Very often, this happens semi-informally, and you may not have slides to support you. Thus, it is more akin to the classic “elevator pitch”, so common in the business and start-up world.

So, how do you do an elevator pitch of your research? How to summarize months, maybe years of work in a few sentences, but still impress, or pique the curiosity of your improvised audience? In the rest of this post, I will share a simple technique I learned years ago, when I failed at doing precisely that.

About 9 years ago, around the middle of my Ph.D., I was doing a three-month research stay at SRI International, a large research institute based in California, which does research on anything from military stuff to education. I was having a nice lunch break with some of the wonderful people I was collaborating with, in the sunny terrace of one of their cafeterias. Then, an older guy comes into our table and asks whether he can sit in with us. Sure enough, we said. I quickly learned that this was Curtis Carlson, then CEO of the institute. A few minutes of conversation later, the moment I was fearing all along, actually happened: he innocently asked me, “what is your research collaboration about?”. I probably blanked out, and mumbled something about collaborative learning tools we were using with some schools. He patiently listened, and then offered a small piece of advice for situations like this: use the NABC model.

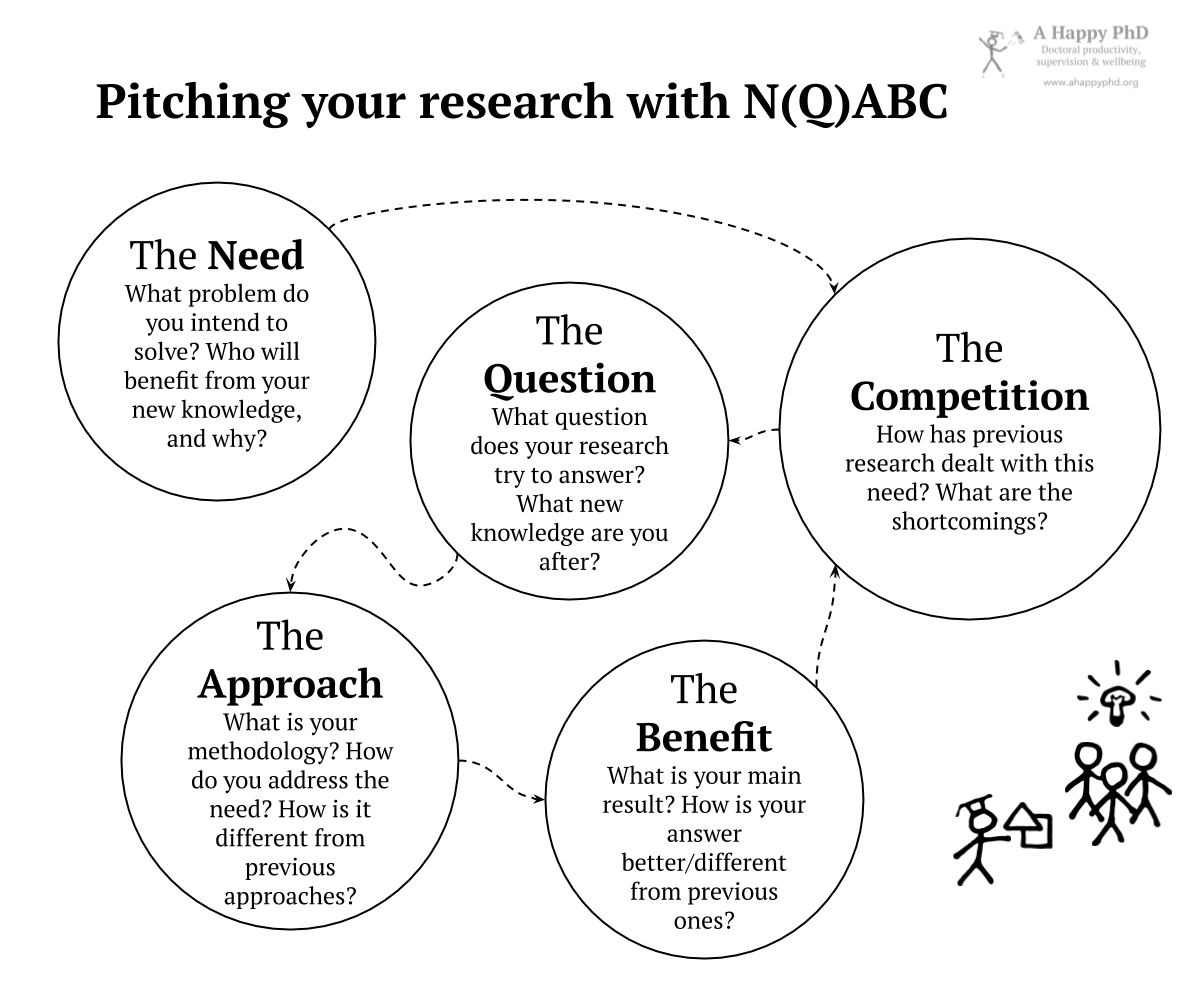

What is the NABC model

As described elsewhere, this simple structure originated in SRI, as a way to develop ideas for innovative projects. Its main focus is the value proposition: what is the added value of the idea for the client/customer. The model suggests that every innovative idea has to solve an important client or market need addressed by a unique approach with compelling benefits when compared against the competition or alternatives. One classic example SRI provides, from real life, goes like this:

“I understand that you are hungry (the Need). Let’s go to the SRI Cafe (the Approach). It is close, the food is good and it is quiet there so we can continue working (the Benefits). The alternative is McDonald’s, which is noisy at lunchtime (the Competition or alternative).”

As you can see, this definition has four elements:

- A Need: Who is the client (the target of the innovation), and what need/problem of theirs are we going to address? how big is that market or collective of people?

- An Approach to solve that need or problem. What is our compelling solution to that specific client need? You can often use drawings, simulations or mockups, to convey your vision.

- The main Benefits of using that approach to solve the need. This can be things like lower cost, better performance or quicker response. Very often these benefits need to be quantifiable and substantial.

- What the Competition has been doing so far, or what are other alternatives the client has (including doing nothing about the need!). Why are our benefits significantly better than these alternatives? Why is this the best value?

Simple, right? Now wait, you say. This all sounds very business-y, and it may be fine for a startup or a big commercial lab. But I am a humble Ph.D. student, and my research is more academic. How does all this apply to me?

How N(Q)ABC looks like for your research… with examples

We have already seen that not every research needs to solve an immediate need (especially, in more theoretical fields). Yet, the exercise of trying to distill in a few sentences what your research does and for whom (and why it may be a good idea), is very beneficial. If nothing else, because that is precisely what you will do for most of your research career, when you apply for funding. Plus, it may help you in connecting with other researchers, and see more meaning in your own project (which is crucial for completing your Ph.D.). How would those NABC elements translate to your humble research paper, or your PhD thesis?

- Need: what is the problem that your research tries to solve? If nothing else, a response can be “we don’t know enough about X”. Very often, especially in more applied fields, there is a societal or practical problem behind it. Do you want to cure cancer patients? Will more knowledge about the history of Italian Fascism help modern citizens understand the current rise of authoritarianism? Why is it important to know what you set out to find out?

- Competition: how have others solved this need so far? This often covers the “literature review” or the “related work” of your research. What did previous research on the problem find out (or fail to do so)? Reduce that body of work to its essence, the gist of what people have done so far in that direction (and what shortcomings those approaches have).

- Question: Very often, after explaining our topic, experienced researchers will delve deeper with a “what is your research question?”. Thus, I have directly inserted it here. In most fields, a research question should guide each paper or whole Ph.D. dissertation. And, in a sense, this question is often derived from previous research (see the Competition). Thus, stating the question1 here is a perfect segway into the next parts of the model, which are more about what you do.

- Approach: This covers both the research methodology you are following (i.e., how you go about answering the question), and what is the solution you found out or propose, to solve the problem. You may mention here any other assumptions or hypotheses you have as well, that were not mentioned in the Question element above.

- Benefits: In the case of a research paper, this often refers to your results. How did your solution perform, if you evaluated it? did your treatment cure cancer, and in what kind of cases? what is the gist of what you discovered about Fascist history? If your research is still preliminary, you can mention the expected benefits of your proposal. You can also circle back to the Competition, explaining how your results compare with prior research. We are in research, not business, so we can also show a bit of critical thinking and include here one or two main limitations of your approach or our study.

Maybe a couple of examples will better drive the point home. If you remember the journal paper that I used as an example when describing my writing method, the pitch could look like:

- Need: Teachers very often are asked to reflect about their teaching, to develop as professionals

- Competition: So far, teacher reflections are infrequent and based on memory (which we know is biased). Sometimes teachers manage to record videos or have observers, but that takes even more time and effort (and thus gets done even more rarely).

- Question: How can we use technology to help teachers gather data about, and reflect upon, their teaching in an everyday manner?

- Approach: We worked with a school to iteratively design technologies that let them gather simple data about the issues they care about. The result is Prolearning, a simple anonymous feedback and reflection tool.

- Benefits: Teachers using the tool in their real classes spent an average of 1-2 minutes per lesson in gathering data. They also mentioned thinking more often about the teaching issues they were asking feedback about. They also said they would not use it literally every day.

And here is another one, for a workshop presentation I will give at a conference this summer. This one is not a finished project, but rather one we are starting (i.e., for which we do not have lots of results yet). Please note the change in order and quality of the model’s elements:

-

Need: Collaboration and collaborative learning is a very important skill. Researchers, but also teachers and students themselves need to understand how they work and learn collaboratively.

-

Approach: Multimodal Learning Analytics (MMLA) uses sensors and other sources of data to understand how collaboration happens across digital platforms and the “real world”.

-

Benefits: MMLA can provide a more complete view of the collaboration process, than teachers just looking at a situation, or analyzing the traces of students using a digital platform.

-

Competition: However, most MMLA is currently done in controlled lab settings, requires complex data gathering setups (e.g., a researcher being there), and its findings are often tied to a particular way of setting up sensors and other classroom elements.

-

Question: Can we come up with more robust MMLA technologies that help us understand collaboration across different classrooms, and which teachers/students can use autonomously?

Simple, yet flexible. That is one of its main values. The other great advantage is that it allows for fast iteration of ideas, be it with your supervisors, other co-authors, or any researcher you come across in conferences and other events. Of course, it also requires a small bit of preparation and rehearsal – you need to memorize your sequence of five elements. But I have found that quite easy, as they often form quite an easy-flowing story.

Update (22.06.2022): We have now added to our PhD Toolkit an editable template (in the form of a canvas) which you can copy to brainstorm your research pitch (alone or together with colleagues) using the NABC method. Of course, you can always do it on paper as well!

Over to you

I don’t know about you, but just doing this exercise has helped me bring some clarity to the talk I’m preparing for the summer. I can easily build a compelling and memorable presentation around this kernel. Just add a few slides with photos, graphs and a couple of keywords and… voilà!

What about you? Try this structure in your next conference, or with your latest paper. Pitch it to a colleague or to your supervisors. Ask them for feedback: what parts are unclear or not very compelling? Then, do tell me how it went in the comment section below.

-

… or a shorter, more direct version of it, since very often research questions tend to end up very convoluted, to accurately qualify what exact piece of the research space you really can explore with your limited efforts and resources as a Ph.D. student. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.