POSTS

The three most common productivity challenges of PhD students

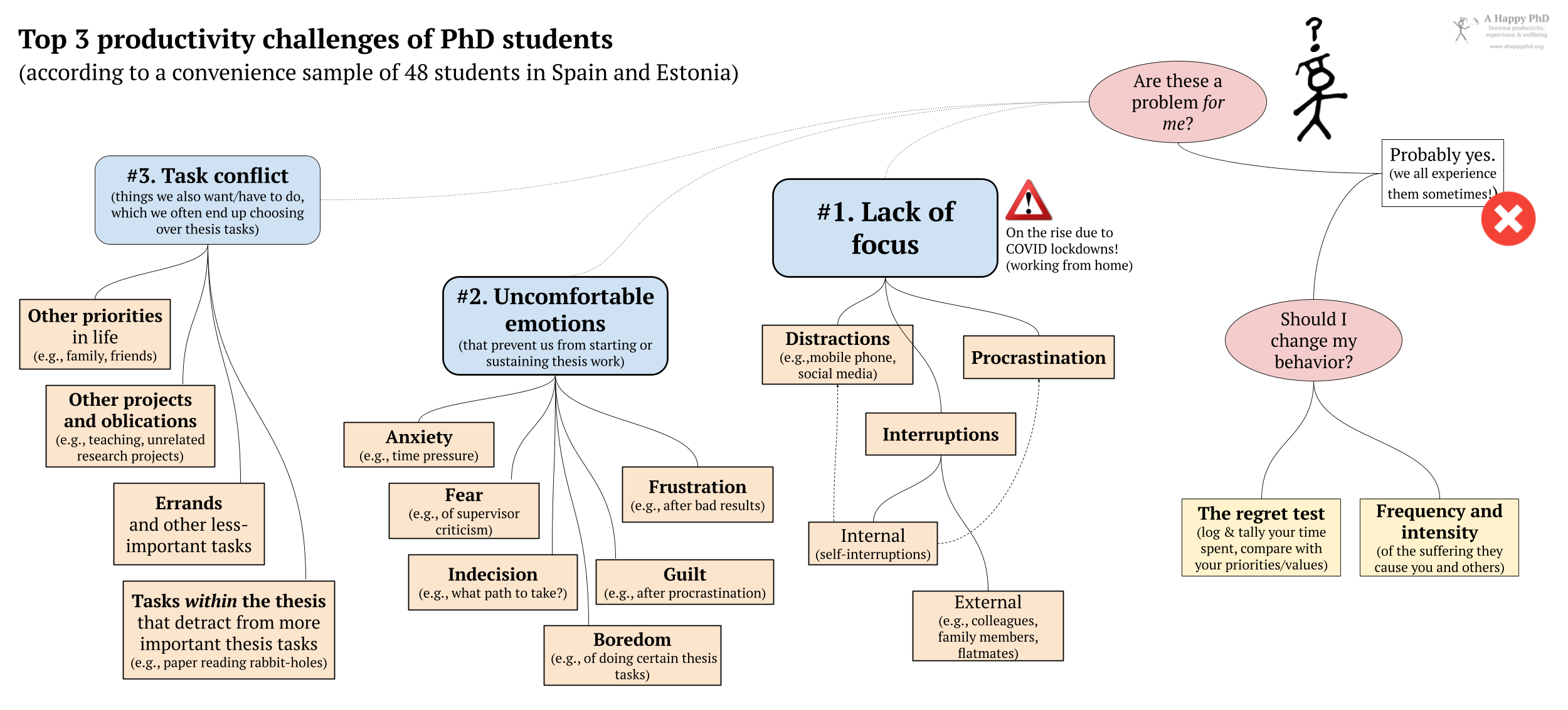

by Luis P. Prieto, - 12 minutes read - 2378 wordsDo you ever feel, during your PhD, that you are not “productive enough”? Guess what, you are not alone. In this post, I share the three most frequently-appearing productivity problems voiced in doctoral workshops we have run in Estonia and Spain. I hope this shows PhD students that they are not alone… and gives PhD supervisors hints about the hurdles their students often face (whether they mention them explicitly or not). Also, I will give a couple of simple rules to know if these are a problem for you particularly.

Global pandemics aside, this past year has been quite interesting in the “A Happy PhD” camp. I have gone from providing advice about the doctoral (and supervisory) journey through this blog, to doing it more directly in workshops and seminars. The workshops touched upon many topics that the readers of this blog may be familiar with: the importance of progress, as well as productivity and mental health advice. I especially liked the doctoral productivity module, where students voiced their struggles about keeping themselves productive. Then, we tried together to come up with techniques, tips and habits to overcome them.

Now, looking at the evidence and outcomes of the workshops (for research and to improve them), patterns are starting to emerge. The same productivity problems (with variations) appear again and again, even across countries. Below, I describe the three most common productivity challenges mentioned by a total of 48 doctoral students, in four different workshops in Estonia and Spain. Of course, this sample is not representative and the results should be taken with a grain of salt. Yet, I hope they illustrate recurrent issues that appear when talking with doctoral students about productivity (both before and after the COVID-19 pandemic hit).

#3: Conflicting priorities, projects, tasks… and rabbit-holes

One very common category of productivity problems people mention is what I would call “task conflict”: we have to (or want to) do many things, but we only have so much time in a day. The consequence, very often, is that thesis tasks (especially the deep, hard tasks that take a long time) remain undone. There are many variations to this theme: the doctoral student that also has teaching duties (which feel more urgent and leave little time to do thesis stuff); the student that is earning her livelihood through an unrelated 8-hour-a-day job, or through multiple research projects that are not about her thesis topic; the student who has children or other family duties they cannot (and don’t want to) forego… there is even a variation of conflict within the thesis itself, like getting into a “literature reading rabbit-hole” for endless hours, progressively farther from the thesis’s focus (and leaving little time for other important research activities).

All these variations have a common feature: they all are conflicts between the many identities or values we hold dear. Being productive in the thesis would be easy if we only valued our research… but we also value having money and food on the table, being a good professional, a good labmate, being a parent, or being a granddaughter. And rightly so. Yet, for many doctoral students, the balance always tips in the same direction: away from important thesis work. Why is that? It seems to depend a lot on our concrete (personal and thesis) situation, and our tendencies1. Some students themselves provided (very accurate) hints about the causes: because thesis tasks seem fuzzy and huge (i.e., lack of clarity on exactly what to do next, or how to do it); because one tends to oblige other people’s requests before our own2; or just because a thesis is no match for a crying baby (your baby), in terms of urgency and importance.

In summary, the main problem is, life is complicated. We will always have these conflicts (before and after the thesis). However, it is possible to find a balance. Indeed, many doctoral students successfully do it. Next week, I’ll try to give tips and advice which may help operationalize this balancing act.

#2: Uncomfortable emotions

This productivity challenge surprised me, because difficult emotions were covered in a different module of the workshops. Yet, after some reflection, it strikes me as an unusually insightful and self-aware response to the question of why we are not productive . Many of us identify as obstacles the most obvious symptoms of ‘unproductivity’ (see #3 above, and #1 below). What these doctoral students were able to identify was the “puppet master” behind these unproductive behaviors: uncomfortable emotions, and our brains’ (sometimes unconscious) efforts to avoid them3,4.

The emotions that PhD students reported as obstacles to productivity, were quite varied. The most common ones were anxiety (e.g., “I don’t have enough time to finish my thesis”) and different forms of fear: fear of criticism by supervisors, fear of not doing the correct thing. Others reported a paralyzing indecision (e.g., when facing multiple courses of action that seemed equally valid). There were mentions to frustration, especially after an experiment gives bad or inconclusive results. Other common emotional hurdles to productivity are guilt (especially, after engaging for a while in #3 above and #1 below) and boredom in the face of difficult or tedious thesis-related tasks.

I can easily empathize. I recall many moments during the thesis when I experienced those emotions… and how they made the idea of working on the thesis quite undesirable. Stay tuned for tips and practices to face them, in following weeks!

#1: Lack of focus: distractions, interruptions and procrastination

The most common category of productivity problems voiced by students in our workshops, were difficulties in focusing or concentrating. This can be surprising to people outside research: for many, lack of concentration is a fact of life (especially, if you have a smartphone in your pocket). Yet, anyone doing a PhD quickly realizes that many research tasks (from reading dense papers to doing rigorous data analysis or communicating clearly in writing) require lots of concentration and skill. A doctorate requires lots of what productivity guru Cal Newport calls “deep work”5.

The causes for the lack of concentration, however, are quite varied. For some students, they are mostly external: colleagues interrupting our work (be it for help or random chatter); or family members and flatmates (for those now forced to work from home). Distractors can also take the form of unexpected tasks that veer us away from the main, important (often, thesis-related) ones. Students also mention a lack of focus due to internal causes (what we called ‘self-interruptions’ in a previous post). It could be because one is trying to do too many things at the same time. Or we procrastinate with leisure activities (‘just one more episode of my favorite show’) or work activities (‘I’ll answer these emails, rather than doing the big, hairy thesis task that scares me’).

In both internal and external interruptions, the mobile phone is often mentioned. Either because we go to it in our self-interruptions and procrastination, or because it is the channel through which interruptions (by other people, or algorithmically-generated) grab our attention.

As you may guess, this kind of productivity obstacle was mentioned even more frequently since the COVID pandemic hit. These days, many students are forced to work from home, or face increased logistic disruptions (from family dramas to public transport shutdowns).

Are these a problem for me? A simple self-diagnosis

Most people I talk to (PhD students or not) recognize themselves in the productivity challenges described above. But, if we all have them… are they really a problem? Aren’t they a “fact of life” that we should accept, then?

Yes… and no.

Yes, conflicts between our many identities and interests, uncomfortable emotions, interruptions and distractions are a fact of life. Trying to avoid them at all costs (and feeling like a failure when we experience them) is only going to make us unhappy. Yet…

No, that does not mean we should throw our hands up and surrender to the chaos, or become puppets to any interruptions and emotions coming our way. Maybe the question is not are these three problems in my life? (the short answer is yes). Rather, we should ask are these three problems making me live my life in a way that is not in accordance to what I value?, or is the impact of these three problems in my life big enough that it warrants a change in my behavior?. These are more nuanced questions, and you may find it difficult to answer them clearly. Here are two ideas about how you could go about answering them:

- The ‘regret test’. This concept, popularized by behavior designer Nir Eyal (in the context of technology design), is simple but powerful. Basically, it is about asking ourselves: do I regret the way I spent my time? (the time I spent in my different conflicting priorities and projects, distracting myself, dealing with interruptions…). This is difficult to do in-the-moment as we spend our time, but can be answered with a bit of reflection. We could, for example, spend a couple of weeks logging (in a diary, or in a calendar app) how we spend our time. Not up-to-the-minute logs, but maybe in 15-30 minute increments. This is quite easy if we use [the calendar trick mentioned in a previous post](https://ahappyphd.org/posts/to-do-list-overwhelm/ – but can also be done simply on pen and paper. At the end of this measuring period, I’d dedicate one hour to tally up the amounts of time I spent in each kind of activity (e.g., quality time with family or friends, binge-watching Netflix, doom-scrolling in Facebook, dealing with colleague interruptions, writing for my thesis, doing data analysis, etc.). Then, I’d compare it with how much I value/prioritize each area of my life6. If the productivity problems above (or other challenges) make me spend a lot of time doing things that are not really important in my life (or little time doing things I value a lot)… maybe it is time to try and change my habits and behaviors!

- Frequency and intensity. The regret rule is all nice and good, but… we all do things we regret, sometimes. We all have weak moments. Another important aspect of these problems is how frequent they are: how often the conflicts, emotions or interruptions make us miss deadlines, are noticeably painful or impede progress altogether. If it is once a semester, I would not fret about it. But, if it is every single day, I would consider doing some changes in how I work. Similarly, you could look at the intensity of the suffering these problems cause. It is not the same to be robbed of 10 minutes of data analysis by our flatmate’s interruption, than missing an important formal deadline which risks us getting expelled from the PhD program. As we saw in our introduction to mental health post, many psychologists consider things a problem when a) they are repetitive and uncontrollable; and b) they cause important suffering to us and to those around us. Here, again, I would avoid simply trying to remember the frequency and intensity of the suffering these problems cause (we humans are notoriously bad at such estimations from memory). Rather, I would keep a journal for some weeks, noting down when these problems arise, and how serious were the consequences. Then, tally up, reflect and decide if a change in behavior is needed.

If, after applying the regret test you find that your time spent is not well correlated with how much you value the different areas of your life, if these three problems cause you frequent and intense suffering, then maybe you want to try changing some of the ways you work. In the following posts I will share tips and practices that may help you in doing so.

If, on the other hand, your time is more or less aligned with your priorities, good for you! You are probably on the good path, and the occasional productivity glitches you experience are more a consequence of the multiple priorities in your life (some people’s lives are much more complicated than others’). You may be just experiencing a bit of productivity “fear of missing out” (FOMO). You can always try to optimize a bit more the way you work (and the next posts will still be useful for you to do so), but do not make a huge project out of it.

Go on, log and tally these things for a couple of weeks. I’ll wait here… trying to avoid procrastinating on writing for the blog (a common problem I face these days). I think I will start writing the next post about how to overcome these productivity challenges, right away.

Or maybe after I make some tea :)

Do you also experience these productivity problems yourself? Are there other big productivity hurdles you experience, which do not really fall into these categories? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header image by Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 Alpha Stock Images

-

This reminds me of Gretchen Rubin’s model of the “four tendencies”, about how one tends to react to external or internal rules and expectations. ↩︎

-

This is what Rubin calls the “Obliger” tendency… anecdotally, I have noticed many of my colleagues and students, which I would place into this category, often struggle with this particular productivity problem. ↩︎

-

Boulanger, J. L., Hayes, S. C., & Pistorello, J. (2010). Experiential avoidance as a functional contextual concept. ↩︎

-

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., & Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 64(6), 1152. ↩︎

-

You can see a description of the concept of “deep work” in Cal Newport’s homonymous book, or a shorter summary in this page, or Cal’s own talks about the topic. The idea is also featured frequently in his podcast (quite recommendable for anyone passionate about productivity in knowledge work). ↩︎

-

One way to do this is to use formal research instruments like the Valued Living Questionnaire, see Wilson, K. G., & Murrell, A. R. (2004). Values work in acceptance and commitment therapy. In Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition (pp. 120–151). Guilford Press New York, NY. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.