POSTS

What kind of doctoral student are you? Motivational profiles and completing the PhD (Study report)

by Luis P. Prieto, - 10 minutes read - 1938 wordsMany factors seem to play out into whether we complete our PhD, or drop out of it. Some of them are external and largely uncontrollable (like financial or family problems), while others relate to our thesis project and motivation. In this new type of blog post (the “study report”), I dive into the results of a recent research study that defines five types of doctoral students, in terms of their motivational profile. Based on this study, I suggest psychological factors and concrete practices to focus on, to improve our chances of completing the PhD.

When I think how blindly I went into my PhD (with little idea about what research was, no funding, and no experience of the research field I was getting into), I still marvel at the fact that I was able to finish. Many of the known factors for dropping out of a PhD were playing against me. Yet, as we saw in a previous post, we can finish a PhD if our basic needs for autonomy (having a say over the research direction, or how to perform it), competence (feeling able to succeed in the research tasks) and relatedness (feeling part of a research team or community) are covered.

These ideas came back while I was reading a recent study, in which Belgian researchers asked N=461 doctoral students to fill in several questionnaires throughout a period of two years. Using these data, the authors tried to tease out the role of these different motivational aspects (and of supervisor support, see the next post), in the completion of their PhDs1.

How to complete the PhD: a general model

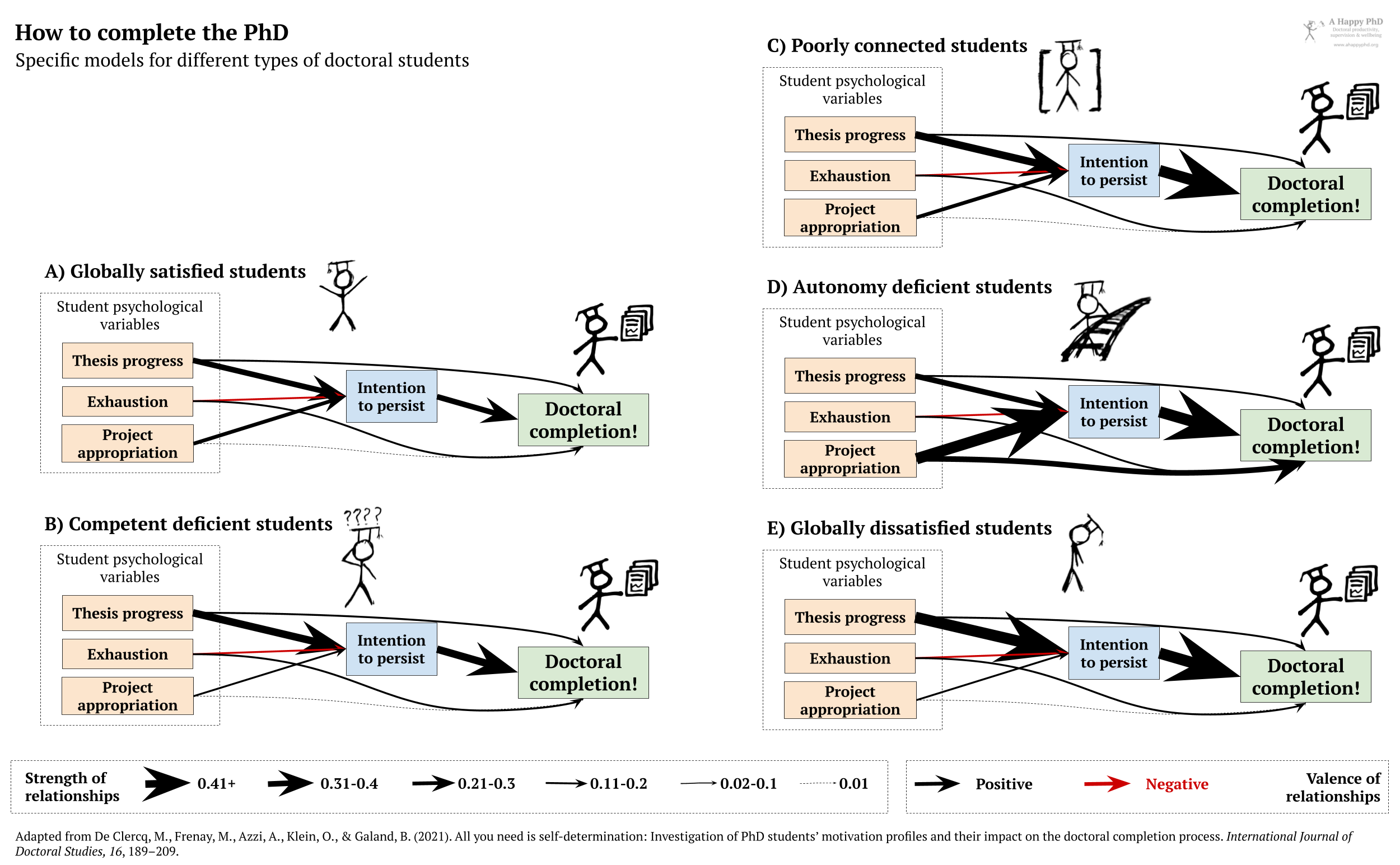

DeClerq and colleagues used self-determination and basic needs theory, refining the theoretical model through the data from five waves of questionnaires. The result was the following model of important motivational factors for PhD completion2:

The left column of boxes should be familiar to readers of the blog. As we saw in a previous post, the perception of one’s own progress in the PhD, the absence of excessive emotional distress (or exhaustion), and the thesis project making sense to us (appropriation), are critical in distinguishing between PhD students that complete and those who drop out of the PhD3. Progress, exhaustion and appropriation, in turn, influence doctoral completion (directly and through our conscious intention to persist on finishing the thesis.

We can already draw some practical advice for PhD students from this general model:

- If I were a PhD student, I would focus first on the “thickest path” to completion. It seems that perceiving steady progress is the strongest factor (both on our intention to persist and directly on completion). Hence, I would read about cultivating the “progress loop”, and implement one or more of the practices mentioned there. Indeed, I still do those myself, long after my PhD finished. I would also have an honest talk with my supervisor(s) about my progress, and the main milestones, indicators and obstacles to stay on track.

- Exhaustion is an odd factor in this model, as it affects increases the odds of completion (!?), but also diminishes them (through the intention to persist). I am not sure how to interpret this… maybe both effects end up balancing out, meaning that many people manage to finish, regardless of exhaustion?4

- The model also shows that these factors are cumulative, so none of them should be totally ignored! For example, appropriation may not have the strongest effect, but if we neglect it completely (e.g., just following orders and not trying to make sense of the thesis project for ourselves), it will substract both from our intentions to persist and complete the PhD. Still, this model helps us prioritize our efforts in different areas.

Five types of doctoral students (motivational profiles)

But, wait, I hear you say… where are those competence, autonomy and relatedness that I mentioned at the beginning? According to DeClerq and colleagues, the PhD student’s perception of how much those needs are covered, define distinct student motivational profiles. These “types of PhD students”, in turn, have significantly different relationships between the factors in the model. Each profile had a different set of “arrow thicknesses”, so to speak.

Which were the five types of doctoral students that the Belgian study found?

- Globally satisfied PhD students think things are generally OK. They had higher-than-average satisfaction of competence, relatedness and autonomy needs. For these students, the roles of progress, exhaustion and thesis appropriation worked pretty much like in the general model above.

- Competence deficient students doubt the quality of their work, and their ability to finish the doctorate. They had average (or higher) satisfaction of their autonomy and relatedness, but much lower perception of competence. For these students, progress had an even stronger influence on the intention to persist, which had stronger weight into completion. In other words, the “thickest path” through progress got even thicker.

- Poorly connected PhD students feel isolated, or don’t get along with their research team. They had average (or higher) satisfaction of their autonomy and competence, but much lower perceptions of relatedness in their PhD. For these students, we also see progress as a stronger influence in the intention to persist, which itself has a very strong influence on completion (once they set their intention to persist and complete, they seem to be less affected by random/external factors).

- Autonomy deficient students feel they cannot voice opinions or influence the development of their PhD. They had lower than average satisfaction of their autonomy needs, but average (or higher) competence and relatedness. For these students, thesis appropriation was the strongest factor influencing the intention to persist and the final completion directly. In other words, the “thickest path” for them was different than for other profiles.

- Globally dissatisfied PhD students see problems in all three areas. They had lower than average perceptions of their doctoral-related competence, relatedness and autonomy. For these students, the “thickest path” is again going through steady progress. Interestingly, the intention to persist in these students had a weaker influence on completion than in other profiles. This could suggest that external factors (e.g., a difficult personal or economic situation) are tipping the scales against the students’ best intentions to persist.

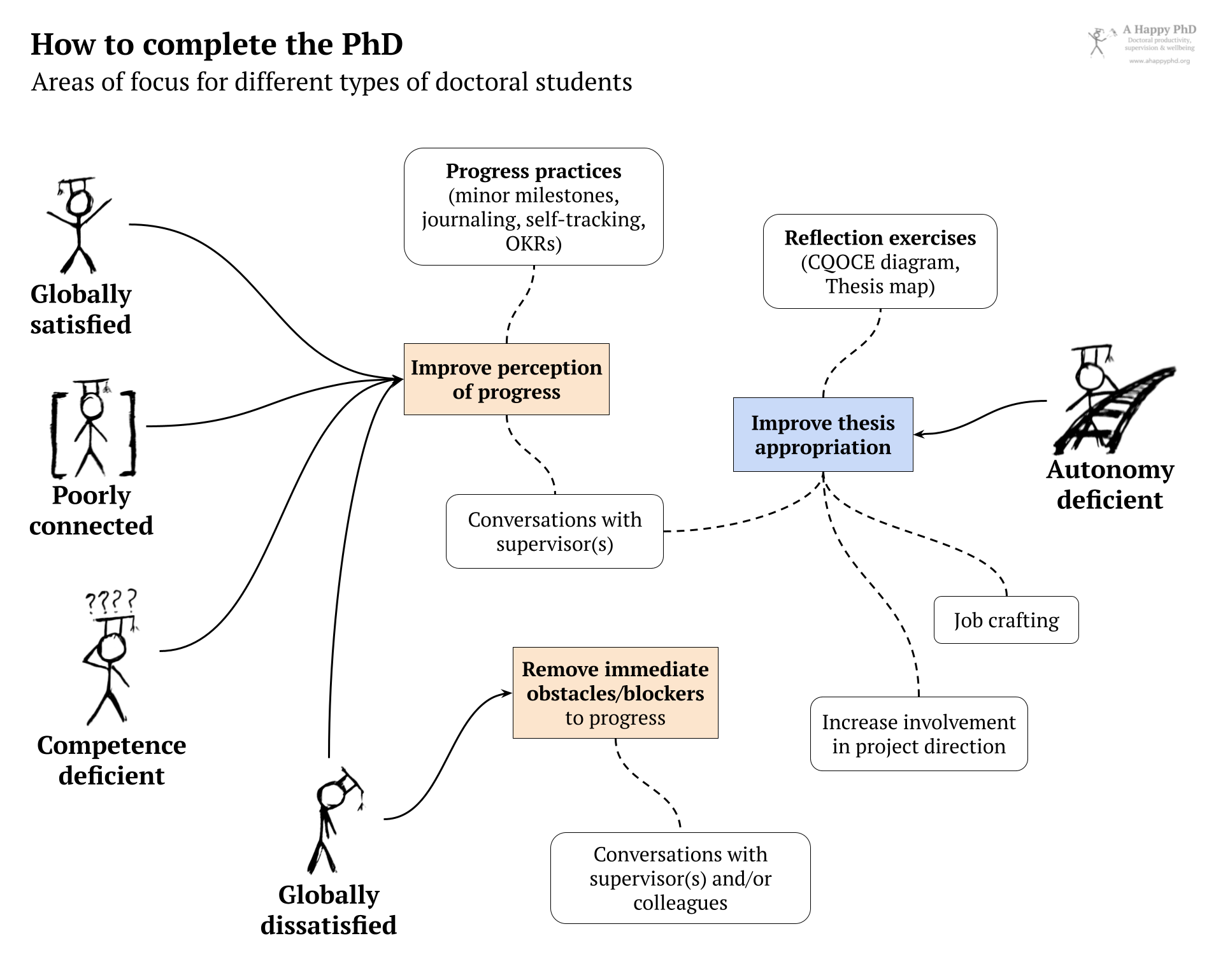

What kind of PhD student are you? What should you focus on?

The profiles in the study were determined using the Doctoral-related Needs Support and Needs Satisfaction (DN-2S) questionnaire5. To calculate ours quickly, we can rate ourselves intuitively (on a 1-5 o 1-10 scale) on these three questions:

- Competence: How confident are you in your ability and progress to finish the PhD?

- Autonomy: How much do you think you have a say in the direction and development of your PhD project?

- Relatedness: How well do you get along with (or feel integrated in) your team/lab?

If we want a more reliable measure, we can take a look at the paper describing this scale, answering the questions in the ‘Needs satisfaction scale’6.

Once we know what is our motivational profile right now (note that it may change over time!), we can get an idea of what areas to focus on going forward. If we do not fall clearly into one of the five profiles above (e.g., all our values are average), we can apply the general model and practical tips above.

- If we are globally satisfied, but especially if we are competence deficient or poorly connected, we should focus on ways of making and better perceiving progress in our PhD. It would also help to talk explicitly with our supervisor(s) about how to make our progress more visible, or how to define intermediate milestones so that these “small wins” slowly convince us of our competence. In the case of the poorly connected, finding ways to meet and talk with other researchers (at your doctoral school, or in conferences and scientific events of your field), would probably help as well (the Belgian study did not delve into this aspect).

- If we are globally dissatisfied, our situation is the most urgent, and again our first priority should be progress . Maybe here I would first look for concrete obstacles blocking our advances, and define (and execute!) very concrete actions we can take to remove them (rather than just ruminating about the problem). These actions will probably include talking with our supervisor(s) about those obstacles (and whether they can remove them for us, or give us ideas about how to do it) and other ways to foster progress.

- If we are autonomy deficient, we should focus more on making sense of our thesis project. We can do exercises like the [CQOCE diagram](https://ahappyphd.org/posts/cqoce-diagram/ or the map of the thesis, and discuss them with supervisors and colleagues. We can also try to make the PhD project really our own (e.g., taking a more active role in steering the project, or using the “job crafting” technique I mentioned in a previous post about purpose).

Caveat lector

All the usual caveats of transferring findings of social sciences studies to one’s own situation, apply. These models are probabilistic, and there are external factors (not included in the models) which could affect you particularly. Further, this research was done in two universities in Belgium – so the models may look quite different if you are doing your PhD in a place with different cultural and doctoral program conditions. Also, I did not mention here the supervisor support factors that the authors included in their study… because that is the focus of the next post. Read on!

Did you assess your motivational profile? What was the result? What other actions do you plan to take in order to improve your chances of completing the PhD? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header image by Pixy.org

-

De Clercq, M., Frenay, M., Azzi, A., Klein, O., & Galand, B. (2021). All you need is self-determination: Investigation of PhD students’ motivation profiles and their impact on the doctoral completion process. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 16, 189–209. ↩︎

-

Actually, De Clerq and colleagues’ model is more complex than the one presented here. I have simplified it to focus on the student motivational factors (and to keep the post short!). In the following post, I will expand this simplified model to cover also factors related to supervisor support. ↩︎

-

Devos, C., Boudrenghien, G., Van der Linden, N., Azzi, A., Frenay, M., Galand, B., & Klein, O. (2017). Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: A matter of sense, progress and distress. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(1), 61–77. ↩︎

-

The authors of the study also note that their model does not look into what happens afterwards, when the thesis is complete (i.e., do they become productive independent researchers, as expected after a PhD?). Maybe these “exhausted finishers” tend to develop a negative relationship with research or academia, and continue down a different professional path (a common occurrence, in my anecdotal experience). ↩︎

-

Van der Linden, N., Devos, C., Boudrenghien, G., Frenay, M., Azzi, A., Klein, O., & Galand, B. (2018). Gaining insight into doctoral persistence: Development and validation of Doctorate-related Need Support and Need Satisfaction short scales. Learning and Individual Differences, 65, 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.03.008 ↩︎

-

More concretely, we can go to pages 44-45 of the paper’s preprint version, finding those ‘Needs satisfaction’ questions that do not have a superscript note, and answering them in a 1-5 scale (from Strongly disagree-1 to Strongly agree-5, reversing those indicated with an ‘R’). Then, averaging our scores for each of the categories (‘Need for competence’, ‘Need for autonomy’, ‘Need for relatedness’). ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.