POSTS

Happiness in the lab, part 2: Purpose

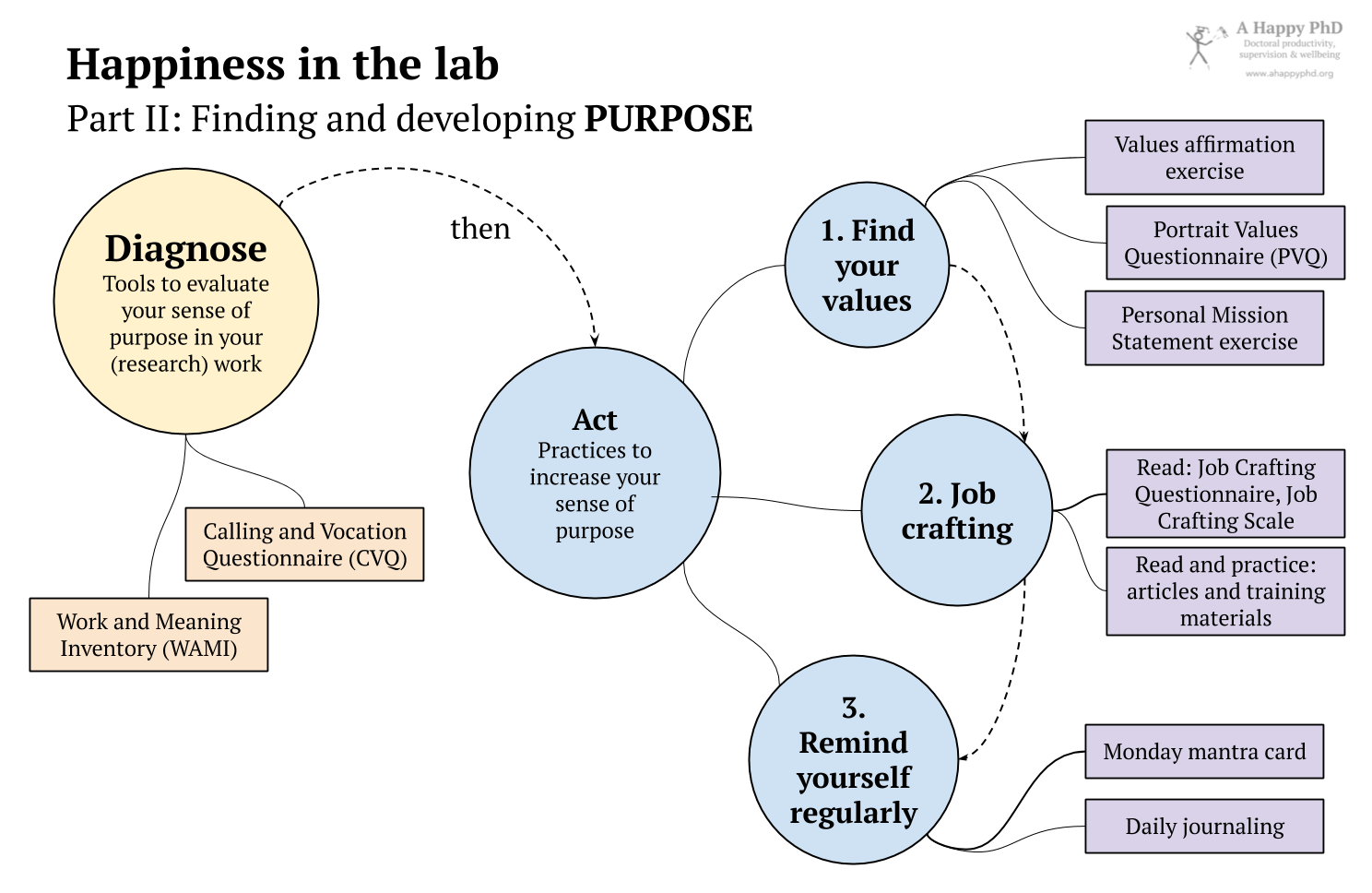

by Luis P. Prieto, - 9 minutes read - 1778 wordsContinuing with last week’s post on “happiness at work”, in this post I explore the first of the four pillars for a happier workplace: the sense that your work has a purpose, that it is personally meaningful to you. Read on to learn to self-assess your sense of purpose at work, and get some ideas on how to make your research work feel more meaningful.

P is for Purpose

As it happened with “happiness” last week, many people will feel that this term is too fluffy and vague to be practically useful. For sure we cannot define (or measure) our sense of purpose as researchers, can we? The course on “happiness at work” defines purpose as the feeling that you make valuable contributions to others (or to society) that you find personally meaningful, and don’t harm anyone. Apparently, there are studies that show that people that work are happier (on average) than people who do not work – but people that feel purpose at work are even happier!

There are several typical avenues to get work to feel meaningful:

- if your work serves a purpose beyond yourself (e.g., I’m trying to find a cure for cancer),

- if it provides opportunities for self-realization (in the form of learning and personal growth, or some other kind of recognition of achievements),

- if it provides some kind of status and/or the opportunity to acquire and exercise power

- if it provides social opportunities, such as making you feel you belong to a community, that your ideas are listened to, or that you have freedom to decide what to do and how to do it

Looking at these avenues, one would think that doing a Ph.D. has many elements to feel like meaningful work: you are working to further human knowledge (sometimes even with clear practical applications), acquiring new knowledge and skills, getting recognition (e.g., in the form of publications or citations), being part of a local or international scientific community… however, this is all very personal. The key issue is whether you perceive these features of your work.

Do you?

Diagnose your sense of purpose

As a way to self-assess how much you feel this sense of purpose in your work, you can try another couple of research-validated instruments, answering them with your research/dissertation work in mind (i.e., not considering any other job/work you may be performing in parallel):

- The Calling and Vocation Questionnaire (CVQ), based on the work by Dik et al.1

- The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI) by Steger and colleagues2

How did you do in these questionnaires? If you did not score very high, do not despair. Many, many researchers have worked for their whole lives without a big sense of purpose about their research (maybe their purpose is about other aspects of their lives, like their family or volunteering outside their job). Maybe that’s why the notion of being happy at work is so foreign to many people. But if this is something you want to change for yourself (and research suggests it can change3), read on for some practices that might help.

Act: Practices for purpose

The course suggests several ways to find more meaning at work, although does not go too much into specifics. After digging a bit more into the literature and other readings, I found a few concrete things you could try out for yourself. However, rather than seeing them as isolated tricks, I’d wager they build upon each other:

- Find your values. It is difficult to find meaning in your research if you don’t know what things are intrinsically important to you. What are your core values? Don’t be surprised if you don’t know what to answer (I didn’t even know what were the possible options!). In the hubbub and busyness of the everyday getting-things-done, this kind of question seldom appears, and we take it for granted. Thus, a good first step would be to take some off time to introspect, to reflect on what are your core personal values. I have found several useful concrete exercises for this (I would try all of them, since each one uncovers different aspects of them)4:

- Try out the simple practice of “affirming important values”. This seems to be especially useful when you ego has taken a hit or we feel evaluated/judged5 (which is quite common during the PhD process!).

- The Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) investigates how much weight you put to different values that seem to appear across cultures. There is no right or wrong answers. The results of this one I have found enlightening, not only to better understand myself, but also the people around me (conflicts often arise just because we value some things and we take for granted that everyone else shares the same values).

- Although not so research-based, I have also found this reflection exercise6 to be quite useful to put things into perspective. It takes some more time (maybe an hour), but it is worth the time, especially if you still feel that you don’t see a clear meaning or purpose about your life.

- Job crafting. Once you know what your core values are, what is meaningful for you, then you just have to find work that aligns with those values. Easy, right? Not really. The research we do, especially during the PhD phase, is seldom fully defined by us, and it is very difficult to make big changes in direction once the research has started. One potential way out of this conundrum in the positive psychology literature is “job crafting”7. In very simple terms, job crafting is about redesigning your work tasks, your relationships at work, and your thoughts about work. Even if you have limited freedom to do such things (especially as a PhD student), all of us can do small tweaks on what kind of tasks we do more often, who and how we interact with, and how we think about what we do in our research. Try out these resources (in order of increasing complexity):

- You can just take a look at the items of the Job Crafting Scale by Tims et al.8, or the Job Crafting Questionnaire by Slemp et al.9, as they ask about concrete behaviors of job crafting. See if you can do any of those in your own research work!

- This article introduces job crafting in more detail, including exercises and examples.

- If you want to get really serious about it, there are more detailed training materials, like this one by the University of Michigan, where this concept originated

- Remind yourself regularly of the meaning that research work has for you (as discovered in the previous steps). This is one of the job crafting behaviors as well, but it is worth mentioning separately, as it is easy to implement with very little time/effort/cost. Two examples of concrete and easy practices:

- Simply, make that core value or mission your “monday mantra”. Write down your main values or mission (the ones that are relevant and aligned with your research work) in an index card or in a post-it, and keep it with you, in your nightstand, or in a visible place where you work. Just look at it occasionally, especially when your morale falters.

- If you want to take this practice up a notch, try journaling at the end of the day about how your workday went… but also reflecting how it aligned (or not) with those important values, and how you could take concrete actions in the future to improve this alignment.

In case you want a visual summary to remember all these tips and tricks, here it goes:

Over to you

Purpose was the first of four “pillars” of happiness at work. I’ll let you in on a secret: when I did many of these tests myself months ago, I did pretty badly (2 out of 5 in the CVQ, for example). In a sense, starting this blog was part of my own job crafting, of finding work that better aligns with my values. And it worked for me. Indeed, I’m even considering starting some small research studies related to the topics of this blog as well (which hopefully would align some of my work tasks even more with my values). Stay tuned for more info on that!

What about you? Did you try any of the self-diagnose instruments or the practices above? did they help you? do you know other ways to bring more purpose to your research work? Let me know in the comments below. As I mentioned last week, the pillars to happiness at work spell out the acronym P.E.R.K.. Can you guess what the “E” stands for? Make your guesses in the comments, or come back next week to find out!

-

Dik, B. J., Eldridge, B. M., Steger, M. F., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Development and validation of the calling and vocation questionnaire (CVQ) and brief calling scale (BCS). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 242–263. ↩︎

-

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. ↩︎

-

See, for example, initial evidence like Tims, M., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 44–53. ↩︎

-

To make matters more complex, it seems that our values also evolve over time as we learn and experience our lives (maybe not radically, but sometimes noticeably). Thus, you can also do these exercises periodically (e.g., every year), to track how your worldview is changing over time. ↩︎

-

Tang, D., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2015). Self-affirmation facilitates cardiovascular recovery following interpersonal evaluation. Biological Psychology, 104, 108–115. ↩︎

-

In case you are curious, this comes from a personal finance blog (of all places). It tries to guide you to find a “personal mission statement” (similar to the mission statements companies nowadays do for themselves), using different exercises adapted from different self-help classics. I was a bit skeptical myself when I first tried it, but found it very useful. ↩︎

-

Wrzesniewski, A., LoBuglio, N., Dutton, J. E., & Berg, J. M. (2013). Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in positive organizational psychology (pp. 281–302). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. ↩︎

-

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. ↩︎

-

Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2013). The Job Crafting Questionnaire: A new scale to measure the extent to which employees engage in job crafting. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2). ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.