POSTS

How I revise my journal papers

by Luis P. Prieto, - 18 minutes read - 3731 wordsAlong with writing your first journal paper, doing a substantial revision to your manuscript upon receiving the reviewers’ comments is one often-cited painful moment of any doctoral process. This complex act of scientific communication involves balancing diplomacy with integrity, creativity and systematicity. In this post, I go over the concrete (and, sometimes, counter-intuitive) steps I follow to revise my journal papers upon receiving peer-review critiques, as well as some basic principles to increase your chances of success and avoid unnecessary suffering.

If you’ve been for some time into your PhD, probably you know the feeling: after what seemed like an eternity of writing, rewriting, getting feedback from your co-authors, rewriting again, dealing with the unexpectedly complicated formatting issues and a surprisingly medieval submission system, you finally submitted your paper to a good journal. Check. Hurray. Then, you just got on with your life: doing the next study, analyzing the next batch of data, reading and understanding a new corpus of literature that seems relevant… Several months later, when you had already forgotten about the paper, an email arrives: major revision. Or, even worse, reject and resubmit.

Ouch.

That big task you had so confidently checked (rather, that host of smaller tasks or milestones you had already passed), suddenly un-checks itself and bites back. You feel your heart sink. You question the whole idea of ever finishing this PhD.

I have experienced this myself many, many times1. Lately, I have been seeing most of the PhD students around me going through this experience for the first time, and how hard it is psychologically. This post is just a way of saying “it’s OK to feel like that – everybody does”… but also that “this too shall pass”, and that publication is actually closer than it was when you had just submitted (even if it does not feel so now). If the response was not an outright reject, probably the reviewers saw value in the proposal. Manuscript revision is an essential part of the research process, of making our ideas and our papers better. And it works. Especially if you follow some basic principles and procedures, and put some time into it. Now, take some time familiarize yourself with the peer review process, if nobody has ever explained it to you in detail2, and read on.

My process for revising journal papers

The experience of getting (often detailed and exhaustive) critiques for one’s work, and having to answer to them and make changes in a cherished artifact of ours, feels rather unnatural for most people. I know it was weird for me the first time. After doing it a few times, however, you get the hang of it. Below I describe, step-by-step, what I do these days once I get comments with major revisions (or rejections) from a journal. Naturally, the process and principles I mention are in a sense very similar to the ones I have for writing papers, just with this particular situation in mind3:

- Do an initial assessment. Even if you, of course, read the dreaded journal reviews email as it arrives, don’t do anything yet. Maybe wait for a couple of days to calm down4,2, as you will for sure feel very emotional in that first moment. Once you have a clear head, read the reviews slowly, calmly, and read your own manuscript (to understand not what you meant in the paper, but what you actually wrote)5. Then, think about what the critiques mean overall for your paper, and whether you want to submit your revised version to this same journal or somewhere else. Such changes in the publication venue are rare6, especially if we did our due diligence when choosing the journal at the beginning of the writing process. Yet, if the reviewers and the editors did not understand the contribution at all, and you find no fault in the manuscript’s clarity, maybe this is not the right community of researchers interested on what you do4. Send this initial assessment/opinion of yours (not more than a paragraph long) to your co-authors, along with the reviews and the manuscript themselves. See if they agree about what the reviews mean and what is the right course of action.

- If you decide to go for a different journal, do not just resubmit the same original manuscript again! Still, consider the comments and make changes… chances are, the same reviewers can get the paper again (as there is a limited number of experts in your particular paper’s keywords), and they will not be happy to see that you ignored all the effort they put into giving you advice.

- If you decide to go ahead and resubmit the paper in the same journal, be sure to set aside several good chunks of time to work on this revision throughout the next weeks/months until the deadline you and your co-authors set2. Really, block the time in your calendar already. Revising is often time-consuming and we tend to underestimate the time it takes. Then, continue to step #2.

- Set yourself up for the revision. Read again the practical guidelines for revision that often come along with the journal’s response email you received (if that’s not the case, check the journal’s submission system, and see what format and options they allow for your resubmission). It should specify quite clearly how the response and the new manuscript should be formatted (e.g., whether they need a clean version of the new manuscript and another one highlighting the changes, etc.). Unless something else is said, the editors will expect from you a letter of response which details the changes done in the manuscript to address the reviewer comments (this letter is often forwarded directly to reviewers upon resubmission)2. Hence, start a new document for this letter with some boilerplate text, and copy after it, verbatim, the comments received from the reviewers, as well as the meta-reviews/comments from the editors themselves (you can find real examples from past papers of mine here and here, using either a narrative or tabular format for the reviewer comments). At this point, probably it is a good idea to label each comment clearly (e.g., “R1.1” for Reviewer 1’s first comment) for easier cross-reference. You can also include a prioritization tag, for internal use among you and your co-authors, stating whether each of the comments is voiced as a major criticism by the reviewers, or a mere suggestion for improvement (this will help you later to calibrate the effort and exhaustiveness you need in your responses and changes to each of them4,2).

- Outline the response and changes strategy in the answers document5. The key word here is strategy. Do not (I repeat, do not) start making changes right away in the manuscript. Take the answers letter/document you just created and, for every editor and reviewer comment, write down two bullet points: a) what would be the gist of your answer to them (e.g., “we agree”, or “we used the definition by …, which needs to be included”); and b) in general terms, what changes would be needed in the manuscript to address the comment (e.g., “add definition to introduction”). Don’t write a lot, but think a lot. Of course, as you go down the different comments, be attentive to synergies or contradictions between reviewer comments (can one same change address two of the comments? how can you address apparently contradictory comments?). Some authors suggest that, rather than going from top to bottom of the document, you may start with those comments you agree with the least, or those that are conflicting with another reviewer’s4. When devising these answers and changes, keep a clear, calm head, and focus on what can be the legitimate concern behind the comment (however hurting the form of saying it was). As one friend of mine often says, you need to look through the comments, not merely look at them7. How can you make your paper stronger or better, with that concern in mind?2 Once you have gist-answer and gist-changes for each and every comment, send this “answer/change strategy” document and the original manuscript, to your co-authors for feedback: do they agree? have you misinterpreted a comment? are there simpler solutions to address the comment? are your proposed changes likely to be considered insufficient? Your team should be clear on what needs to be done, before the messy work of revision starts.

- Iterate on the answers/changes strategy. As you and your co-authors progressively agree on the general approach to address comments, start adding a bit more flesh to the responses (what do you understand the comment means? to what exactly will you agree?) and to the changes you propose to do in the manuscript (e.g., write snippets of the new text to be changed/added, especially for the more tricky parts of it; find and add new references needed, etc.). But do this fleshing out on the answers document, not the manuscript (yet). There will probably be still interactions among comments, new ideas that that can come up as you read newer studies in relation to what was criticized, and it can be hard to keep track of all the changes in two documents at the same time. Needless to say, this step involves several back-and-forth exchanges with your co-authors, as they suggest specific strategies, phrasing or add details to what should go into the changes.

- Change the manuscript. Once the changes strategy (and maybe some particular snippets of new text) are clear and agreed, you can start doing changes in the manuscript itself. Sometimes, I do a first pass just locating the parts of the text that need changes, and I add just a comment there about what I need to do (e.g., “TODO: mention literature about X and improve argument line to highlight Y”). Then, I just go solving those comments by making changes in the text (remember to activate your word processor’s “track changes” or “suggesting” functionality!). Once you finish, if you have access to a professional proofreader (or someone more proficient in the English language than yourself), it is recommended that they give it a pass looking more at the flow and clarity of the text5.

- Finalize the answers document. Once you have resolved all the edits that were needed in the manuscript, come back to the answers document (which should be quite good already), and add the final layers of polish to it: check that the answers to reviewer comments are clear and polite (see the principles below), add concrete quotations from the manuscript to illustrate some of the changes done, add concrete locators and references so that the reviewers can find where the changes are located in the manuscript (e.g., “we have changed the arguments as per the reviewer suggestion, see section 2, 2nd paragraph/page 3”). You can see what I mean from the examples here and here. Then, of course, send both the manuscript and the answers document to your co-authors, for a final round of feedback.

- Final checks. Once everyone is happy with the new version of the paper, it is time to prepare the resubmission: check again the concrete guidelines for revision given by the journal, as well as the general formatting guidelines of the journal. Check out the journal’s online submission system, to see if you have all the files and information that you need for resubmission. At this point, it is common that the manuscript has grown to address the questions and comments from reviewers. If now the paper exceeds the expected length, include that fact in the letter to the editors, and be open to work on reducing it if the editors think that length is more important than what you think is fully addressing the reviewer concerns (that varies a lot from journal to journal). Any other critical issues or difficulties that you may have encountered while editing (e.g., addressing reviewer comments that go in opposite directions), you can also mention in that “letter” that opens the answers document. And then, just…

- Resubmit!

This process may seem a bit complicated, if you thought that revising a paper is just going to the document and making some changes. But, believe me, being systematic during the revision process is even more critical than when writing the paper. And that’s what research is all about, really. Being systematic.

Some principles to keep in mind while revising

In the same way that I gave my 10 Commandments of writing scientific papers, so that you know why the writing process is done the way it is (and to help you step out of the process and improvise with confidence, if necessary), here I also would like to give you a few basic principles to keep in mind while revising your journal papers:

- Be aware of your emotions. For a career in which one is supposed to put rationality and logic first, research is surprisingly emotional, as the effort we put into our work and ideas, makes us identify with them. Revising one’s own journal papers is maybe one of the most emotional parts of it. Hence, when reading the reviews and writing your responses, be aware of your emotions, and avoid situations that can trip you up4. If you are feeling enraged by the reviews (especially in the moment of their arrival), maybe it is a good idea to calm down, even wait for a few days, before re-assessing what was meant, what valid points may be hiding under those remarks, and going on with the revision2.

- How did I contribute to the problem? Related to the previous point, sometimes reviewers are wrong, sometimes they read in a hurry and overlook things that are actually written there. However, these “wrong remarks” also pose opportunities to make the paper better. Think about your future readers – chances are they will also be in a hurry, and they may also overlook what this reviewer passed over, or did not understand. Ask yourself if there are better ways to convey that idea, or to bring it to the forefront more (either through emphasizing, or repeating elsewhere, or using different, less ambiguous vocabulary). Since you cannot change their lack of attention, work on what you can control: the text.

- Do not be discouraged. One of the first emotions that usually pops up during this process of revision is dispair: you see a document in which a person (supposedly an expert in your field) is giving you a dozen reasons why your paper is bad8. It is normal to feel that your work is shit, and that you’re never going to finish this review, or publish this paper, or finish the PhD. But it’s not about you or your work – it’s just that researchers tend to be systematic people! (see #7 below). Reframe it as a learning, an improvement process4: you are making the paper better, more understandable for others, making your knowledge easier for fellow researchers to digest and build upon. If you got a “major revision”, cheer up! In my experience, those papers have a high chance of finally being accepted, if the authors put in the work (and follow these principles)4.

- Be polite and use evidence9. When you are answering to a reviewer, however lousy you think their review was, think about this: this is a real human being, fallible, but also generous enough to spend some time trying to understand and (hopefully) trying to help you make your paper better… and they are doing this for free, on top of an already busy schedule. Hence, treat them with respect, and think of them rather as consultants, not adversaries4. A brief “thank you” here and there will not hurt either2. If, in the end, you have to disagree with them, do it without being disagreeable: just point to the evidence that supports your position, while acknowledging that the other person may have understood otherwise.

- Collaborate: use your co-author team extensively during the whole process, to double-check your interpretations and strategies. Chances are that they have done this process quite a few times already, and they may know better what works, or some other tricks of the trade… if you give them the opportunity to show you. You can also contact the editor, even before the resubmission, if there are problems that make a good, exhaustive revision unfeasible (e.g., reviewers having non-compatible views of what the paper should look like, etc.).

- Iterate, iterate, iterate… but do not touch the manuscript until later. This one is very unpopular, and a bit counter-intuitive. Why iterate? what one really desires is to finish this whole business, be done with it! However, as I do for writing the papers themselves, I firmly believe in the power of iteration while revising. We never get the approach, the idea, the argument, right on the first try. This is also why I advice to not touch the manuscript at the beginning: in this messy, iterative process, you are bound to put some things in the manuscript and forget to put them in the answers document, or vice versa. This initial strategizing will also help you detect and exploit synergies and commonalities between different reviewer comments. You may have the impression that the revision is stuck because you have not even touched the manuscript but, in my experience, you will spend less time overall if you wait and edit the manuscript once the answers and editing strategy are clear. For one, you will not need to delete stuff you wrote as often! (which is always painful)

- Be systematic, be exhaustive4. This capability to be systematic, to exhaustively look at every issue in your work, is one of the key researcher skills or attitudes, which we learn during the PhD. Once we address all the reviewer comments, we just need to show the editor and the reviewers all the work we’ve done5. This includes clearly labeling every comment, and cross-referencing them when needed, explaining what changes have been done in response to each comment, and where exactly to find them. This also involves looking for recent related literature that may have come out since the paper submission, and adding it where needed (some of it may actually help respond to the reviewers’ comments!). The only exception to this exhaustiveness may be the listing of every minute change that you probably had to do to make the whole paper flow and read well again, after all the changes; maybe just a couple of examples of this would suffice. The answers document need not be long just for length’s sake!

- Keep your integrity. By integrity, I don’t mean what is often found in the arts, the artist’s integrity that says “this is my work, and it should not be defiled by other people’s opinions!”. I mean the researcher’s integrity to find knowledge ethically and communicate it clearly. By following all the principles above, one can fall for the temptation to just stop all critical thinking and just do what the reviewers ask, word-by-word, even if it is clearly not the right thing to do. Rather, a researcher says “this is the evidence, this is the knowledge we got – let me explain it as best as we can, especially since people seem to misinterpret it in this or that way”. If you have to disagree with the reviewers, do so. Politely. Argue why you think it will not make the paper better (hopefully, using criteria other than just aesthetical taste), explain what is the intention you understood is behind their comment, and which way of addressing it you think is better than the one proposed by them.

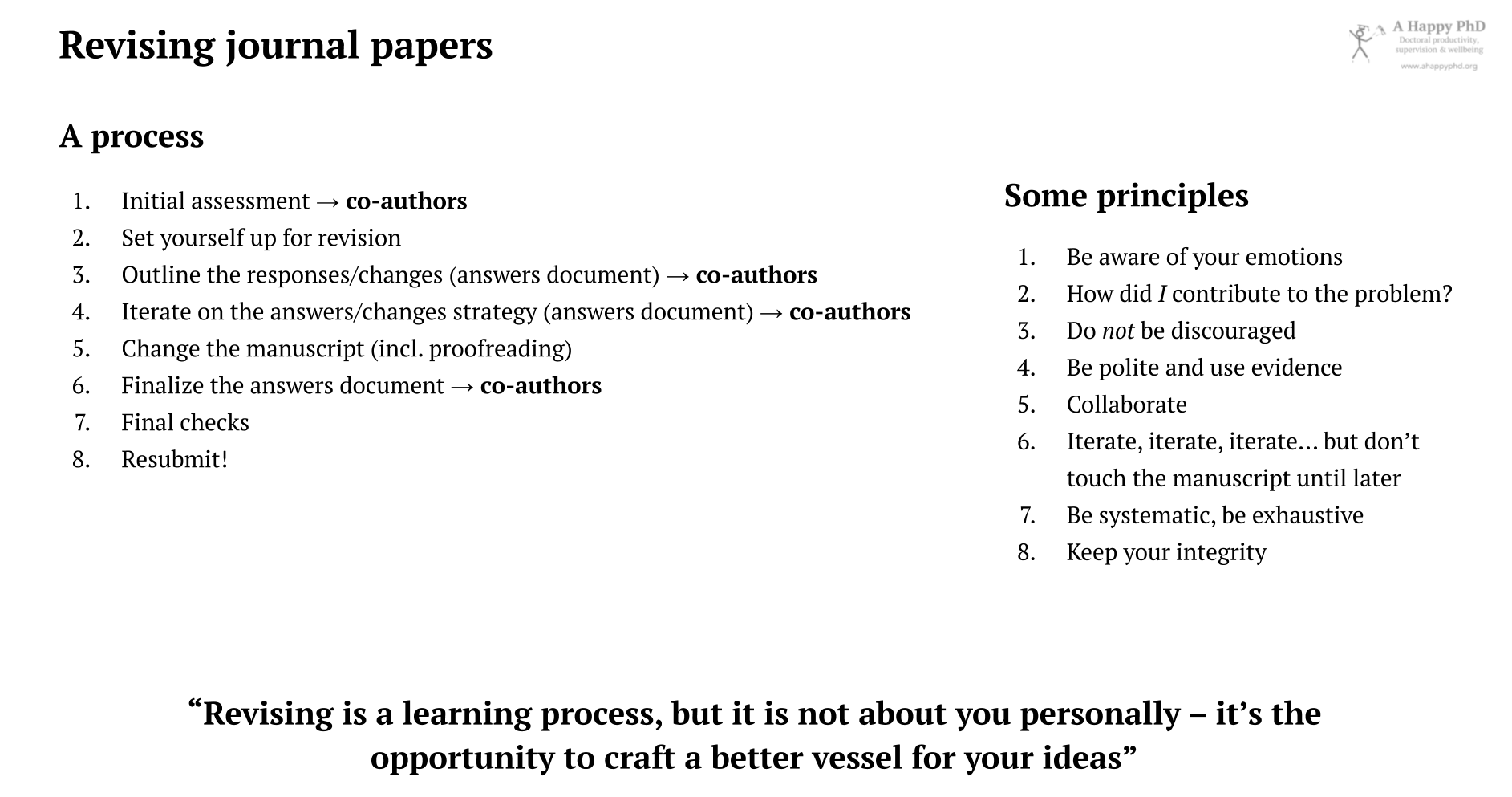

In the figure above you can see a summary of these steps and principles journal paper revision. If those are too many or too hard to remember, don’t worry. I hope at least you will take this away from the post: Revising is a learning process, but it is not about you personally – it’s the opportunity to craft a better vessel for your ideas.

Happy revising, and take care.

Do you also have tips or tricks about how to revise journal papers? What aspect of it you find most challenging? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header photo by nicmcphee.

-

I have never had a journal paper accepted without at least a round of major revisions, I think – and I have 14 of them as a first author (meaning, I was feeling the full emotional blow from those initial quasi-rejections). Plus, all the other papers I co-authored, which also were not fun to receive revisions about. ↩︎

-

LaPlaca, P., Lindgreen, A., Vanhamme, J., & Di Benedetto, C. A. (2018). How to revise, and revise really well, for premier academic journals. Industrial Marketing Management, 72, 174–180. ↩︎

-

Disclaimer: this process represents what I have found works for me, in my field of research (educational technology) and other adjacent fields that I have certain experience with (technology, education, psychology). Yet, I have found similar advice in the literature about this topic (see the footnotes). In any case, as they say, “your mileage may vary”. Take especial care to read the concrete instructions from the editors about how to handle/format the response to the reviews (those will take always precedence). Probably it is also a good idea to check with your supervisors/co-authors whether this kind of process would work for them. ↩︎

-

Provenzale, J. M. (2010). Revising a manuscript: Ten principles to guide success for publication. American Journal of Roentgenology, 195(6), W382–W387. ↩︎

-

Pierson, C. A. (2016). The four R’s of revising and resubmitting a manuscript. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 28(8), 408–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12399 ↩︎

-

Altman, Y., & Baruch, Y. (2008). Strategies for revising and resubmitting papers to refereed journals. British Journal of Management, 19(1), 89–101. ↩︎

-

See Sharma, K., Alavi, H. S., Jermann, P., & Dillenbourg, P. (2017). Looking THROUGH versus looking AT: A strong concept in technology enhanced learning. European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, 238–253. ↩︎

-

Or much more than a dozen. One study in a particular field found an average of 20 comments in each review they screened – see Law, R. (2008). Revising Publishable Journal Manuscripts. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 8(4), 77–85. ↩︎

-

Williams, H. C. (2004). How to reply to referees’ comments when submitting manuscripts for publication. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 51(1), 79–83. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.