POSTS

Defusing task conflict in the PhD

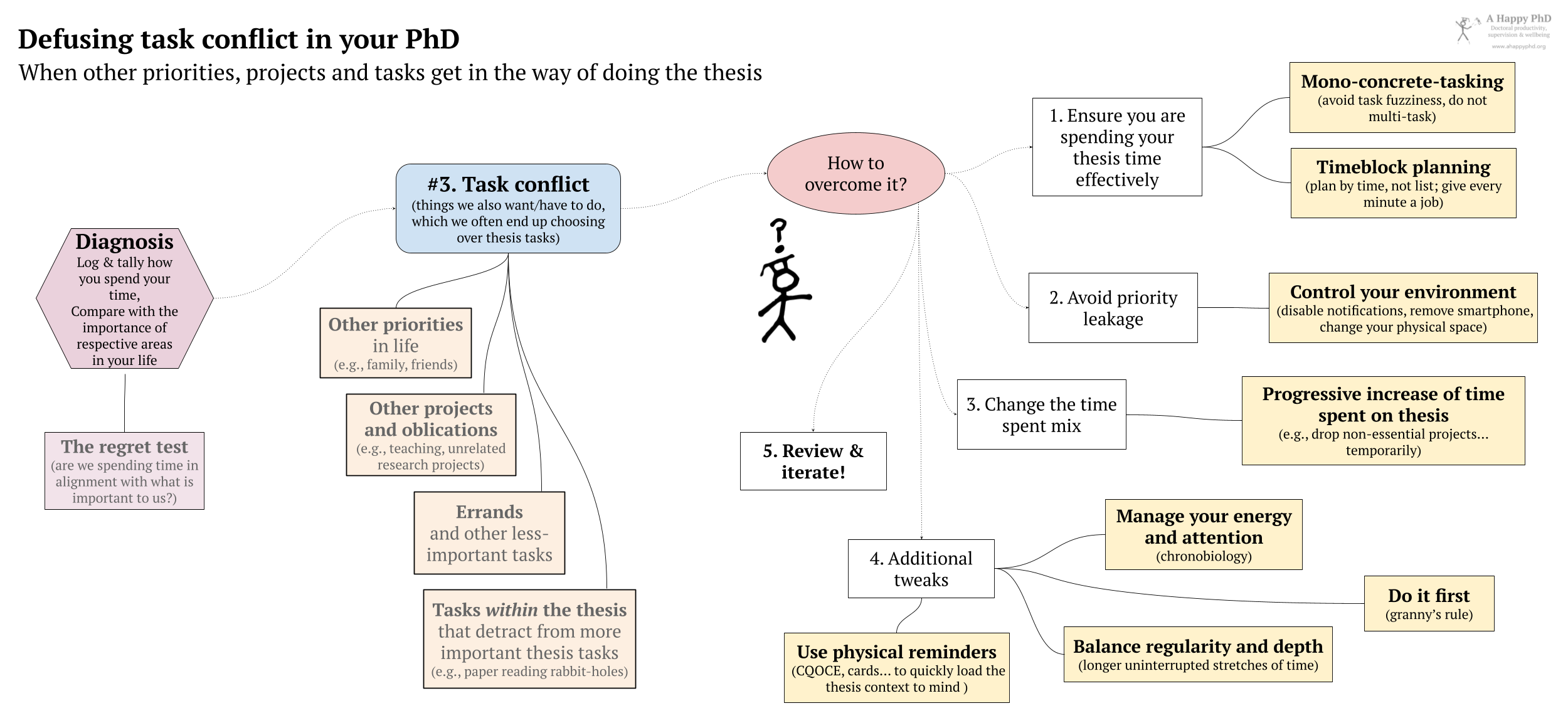

by Luis P. Prieto, - 18 minutes read - 3694 wordsAs we saw in a recent post, “task conflict” is a common productivity challenge of doctoral students. As PhD students, we often have to juggle different identities, priorities, jobs, projects… along with doing the thesis itself. Yet, so often, it is the thesis-related tasks that keep getting pushed back. In this post, I will go over tips, practices and techniques that might be useful if you find yourself struggling with this particular challenge in your PhD.

We all have 24 hours in our day. 1,440 minutes. That’s a lot of minutes… yet most of us feel “time deprived” on a daily basis. For many of us, doing the thesis is not the only important thing going on in our lives: we have to teach classes, or an unrelated research project is paying our salary, or we have to take care of important family issues regularly. Not to mention self-care, from sleeping to exercising or having “off time” with friends. But, for quite a few PhD students, there is one ball that gets usually dropped in this juggling of priorities and tasks: the thesis.

In a previous post, we saw that this common productivity problem originates in the different identities we hold dear (as a doctoral student, instructor, salaried researcher, father/mother, etc.). We also saw a simple way to measure this problem: to log and tally how we spend our time, for a couple of weeks. And then, compare it with the relative importance that we assign to those different areas of our life.

Aside: We may be tempted to gloss over that task above and try to reconstruct our past two weeks from memory. That does not work well (the result will reflect more our tendency to wishful thinking or baseless self-flagellation, than actual reality). Think of it like trying to fix our finances on the basis of how much we imagine/remember we spend on things… rather than the actual expenses in our bank’s account statement!

This “time spent statement” already gives us an idea of whether there are parts of our activities that we regret, that take an amount of time disproportionate to how important they are for us. If I spent 20 hours this week on Netflix and 10 hours on my thesis… is it because watching shows is twice as important for me as finishing my PhD?

Now we have detected some time-importance imbalances (e.g., “I want to spend more time on my thesis research” and “I spend too much time doing emails and looking at Instagram”). What can we do next? Here are a few strategies to try, described roughly in the order I’d try them:

Get into the habit of mono-concrete-tasking

This is more of a basic, foundational productivity habit for tasks that require concentration and (cognitive) skill. Maybe in other areas of our life we can get by doing multiple things at the same time (I personally like hearing podcasts while I do household chores)… But that seldom works in thesis-related activities. The brain does not really multitask… it switches back and forth between the things we do “at the same time”. What happens when we try to write a paper and occasionally check our email? The brain has to repeatedly “load and unload” the 37 concepts we were trying to keep in mind while writing that paper paragraph. In my experience, the results are not pretty: I make errors, I forget things, and only half-baked ideas come through. If you are working on your research, just work on your research.

Along with the temptation to multitask, task fuzziness is the other big problem many of us face when trying to work on the thesis. Contrary to other areas of our lives (you cannot get much more concrete than “pick kids from school at 5pm”), our thesis-related tasks can be wonderfully vague: “continue reading papers”; “finish conference paper”; “design experiment”, etc.

Here’s a quick test. Look at your to-do list (I assume you have one; and if not, I hope you have a good reason for that :)). Are your non-thesis tasks way more concrete than the thesis-related ones? Can you say clearly how much time each task will take? (e.g., “picking up the kids” has a concrete length, even after accounting for bad traffic – but, what about “finishing the paper”?).

Our brains are judging our odds of success at doing stuff all the time. If the evaluation turns out positive, we feel motivated to do that; if not, our brains will look for something with higher chances of success. This is why I end up “doing email” (my brain knows it can “do email” with high chances of success), rather than “coming up with the right theoretical framework for the next study” (or whatever my procrastinated task of choice is).

Thus, we need to make our tasks concrete enough, so that we know what are the steps involved (= high chances of success –> more motivation). That is why the paper writing method I proposed in this blog has 10 very concrete steps. That way, I can transform the big, abstract task of “writing a paper” into concrete tasks I know I can do. Never allow a task in your main, daily to-do list, unless you know how to do it, and how long it will take. If you don’t know, decompose and rephrase them until you do (e.g., go from “do X” to “do Y for 1 hour; then do Z for 2 hours; send the result to W”).

What is a good technique to get into this kind of mindset and making it stick? You guessed it: the Pomodoro technique. Just do ‘pomodoros’ of your (very concrete) thesis tasks until you finish them. If you are used to multi-tasking on fuzzy tasks, or being not very concentrated while you work, this simple habit of reformulating thesis tasks to be more concrete, and then doing them through pomodoros, will vastly improve your thesis productivity. Even before you dedicate a single extra minute to the thesis.

Timeblocking: the diagnosis is the prophylaxis

Once we got the basics covered (concretization and mono-tasking), let’s try something specific for the multiple priorities problem. If we did the “time log and tally” diagnosis I mentioned above, we have already shifted our mindset from task-focused (how many tasks did I check off the to-do list today?) to time-focused (how much uninterrupted time did I dedicate to the thesis today?). This shift is crucial when we try to apply one of the most powerful productivity techniques for the PhD: timeblock planning.

In a sense, timeblock planning is the same as the logging/tallying of our time… but in advance. Basically, to “give every minute of our (work)day a job”, as productivity author Cal Newport likes to say. I used to run my days from my (often huge) to-do list: once a task was checked off, I looked in the list for the next task (or, more often, I read emails until I found something to do). The idea of timebox planning is that we plan our days, time-wise, and in advance (e.g., the evening before). We assign particular stretches of time to concrete tasks (as if we had an “appointment with ourselves”). When doing this distribution of time, we take into account, not only existing meetings and appointments, but also the relative importance of different priorities or areas in our life (more importance –> more time! and don’t forget the self-care). Then, we try to execute our day as planned, as this sequence of “appointments with ourselves”. Whenever we fail to finish what we intended or unexpected changes occur that warp our plans (as they inevitably do sometimes), we create a “next best” alternative plan for the rest of the day. And then we try to execute it as best we can. Rinse and repeat.

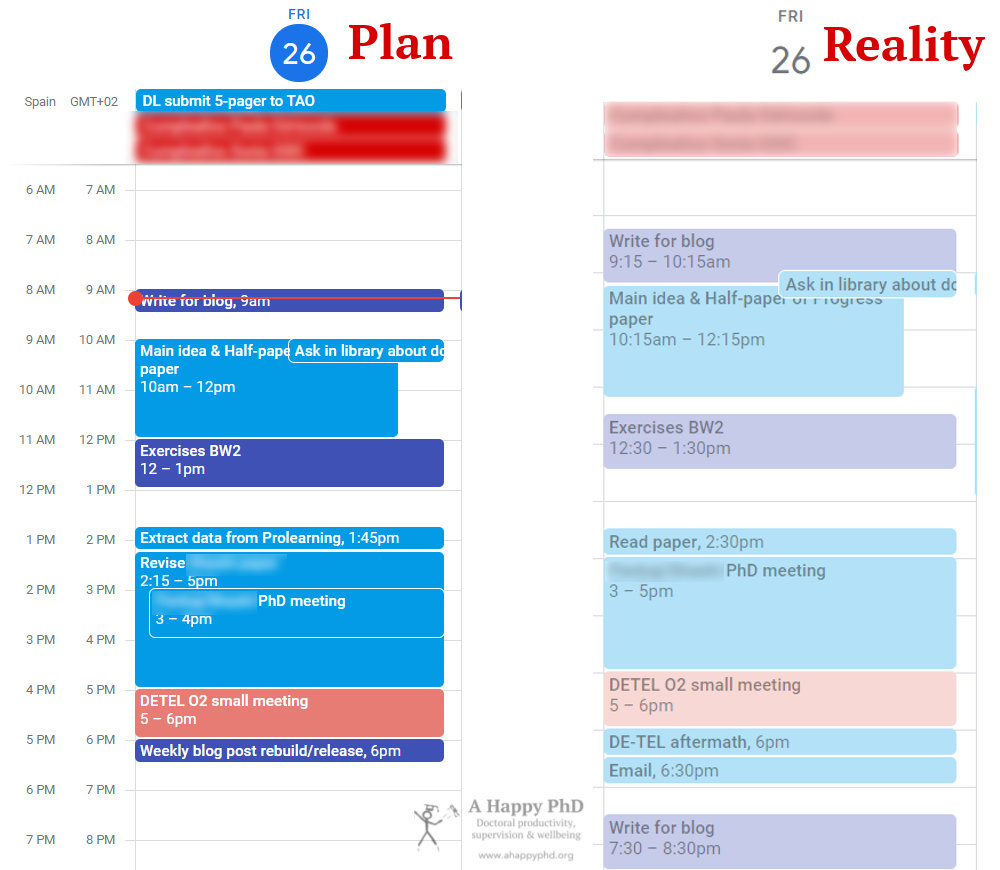

How does this look in practice? If one is used to calendar apps (e.g., Google or Apple’s Calendar), we can easily create events for our tasks, as we do for our meetings. In my weekly review, I often do a first rough timebox plan for the week (at least, of the big chunks of time needed for important –not necessarily urgent– research tasks). Then, I tweak it as needed during the rest of the week. Take a peek below at my calendar for today (and how it looked originally). We could do it just as easily on paper (see the examples from Cal Newport’s blog). Really, any random paper notebook will do. The important thing is to always keep the timebox plan at hand, so that we know what to do next (and so that we can make plan changes when we need to).

I already mentioned timebox planning in passing when talking about avoiding to-do list overwhelm. After implementing it, I have never looked back to a big to-do list. One common benefit I noticed when transitioning to this mode of working is that more “deep work” got done, even without changing much the time I allotted to my different priorities. I spent less time doing “shallow”, reactive tasks. Also, it helped me be less of a perfectionist: rather than “writing the perfect introduction to my paper”, I would try to “write the best introduction I can write in two hours”. Or, even better, “outline the intro for one pomodoro; then write it for the rest of the two hours” (concrete tasks, remember?). Plus, as I notice which tasks take longer than I originally expected, I learn how much time different kinds of tasks actually take, and I start to make more realistic plans for my days (I’m still not perfect at this, by the way). And a final advantage of timeblocking: it has built-in diagnostics! Now, at any moment, I can look at my weeks, tally up the time dedicated in different areas, apply the “regret rule”, and try to plan differently next time.

Seriously, try it for a couple of weeks and see if it works… you may never have to touch a to-do list again.

Prevent priority leakage: control your environment

Once we are used to mono-tasking and timeblock planning, many of our task conflict worries should be gone. Yet, these strategies may not completely solve the problem. Yes, we have a plan for the day, and we try to execute it, but then something (and email, a call, a message) or somebody comes in and puts tasks in our plates that we did not anticipate. Our nice plan goes awry, as tasks from other priorities leak into the time we wanted to dedicate to the thesis. The way we spend time no longer passes the regret test. And the same happens the next day. And the next.

Here again, we need to think carefully about our different priorities, separating the grain (those tasks that we want to be interrupted about because they are urgent and important) from the chaff (a random workmate email that is neither urgent nor important). Then, we need to tweak our environment to prevent that unwanted leakage. Classic examples of this tweaking include:

- The biggest culprit of priority leakage is, of course, our smartphone. Learn how your phone notification system works, and de-activate notifications for all but the really important, time-sensitive contacts and apps. When doing timeblocks or pomodoros, use airplane mode if at all possible.

- Learn how to de-activate email notifications (and any other desktop notifications) in the computer. If parts of our work really require timely response to emails, we could activate notifications for set periods of time (and double-check with our supervisor/employer what these requirements exactly are – and negotiate!). Again, we need to ensure we de-activate notifications when timeboxing/pomodoring. Personally, I’ve lived without email notifications for a decade now, and it has never led to really important problems.

- If the leakage is rather caused by people physically interrupting us as we work, we can try adding signals to others during our focused periods (e.g., the classic ‘do not disturb’ sign). We can also change our physical context completely, by going to work someplace where people will not interrupt us: a nearby park, university library, etc. Once this becomes a habit, the mere act of going to the “deep thesis work setting” will put us in a state of focus almost instantly, as the brain learns to associate that particular space with uninterrupted work (this happens to me in our university’s library, for instance).

Change the “time spent mix”… or reduce scope and expectations

Once we regularly mono-task and timeblock without priority leakage, we know our thesis-related time is well spent. If we still regret some of the time we spend in other activities, or notice a lack of progress in the thesis, there is only one major lever left to pull. Progressively increase the time(blocks) allocated to thesis work.

A good moment to try this conscious shift is during our “weekly review”. Once we place our “basic blocks” in the calendar (sleep, self-care and exercise, unavoidable commitments), we put more (or longer) blocks related to the thesis (remember, assigned to concrete tasks!) than we had last week. Of course, that will mean less time for our other projects and priorities, so it will be tricky. Do not just pile up 12-14 hours of work a day, that is not sustainable for the length of a PhD!

This is also a good moment to think whether all those projects are really essential, or rather “nice to have” (or a nice favor to others). If we are in this problematic task conflict situation, maybe we need to drop the less important of those other projects (at least temporarily), if we want to see good progress on our thesis.

What if all priorities are essential? What if there is literally no way to reduce the time spent on them? First of all, I’d think it over again more deeply (we tend to jump to this conclusion too fast). We can talk about it with family or close friends, and try all the other tricks in our decision-making process. Once we are sure there is really no way we can put more time on the thesis in a sustained manner (I’ll say it again, long hours are not a long-term solution, and a thesis is long), it is time to have a serious conversation with our supervisor(s) about the situation. But not an abstract conversation – a very concrete one! By now we have hard data on how much time we spend on the thesis. Say it out loud: “look, I’ve tried W, Y and Z, but I find it impossible to dedicate more than X hours a week to the thesis”. Once the fact is on the table, we can problem-solve together with our supervisors: Are there other strategies that could work? Is there a way to make scientific contributions of the kind we want to make, spending this kind of time? How long will it take to complete the thesis at this rhythm?1 Can we reduce the scope of the thesis without making it pointless? Maybe our supervisors have ideas for research tasks or studies that are in our original plan, but are not essential for a thesis to be finished. Maybe there are alternative ways of doing the research that are less effort-intensive but still valid. Maybe they will find it unacceptable. Maybe a change in the supervisory team is needed. Having our thesis plan and CQOCE diagram at hand during this conversation will be very useful to ground the conversation and draft potential alternatives. It will be hard, but this conversation will at least unearth problems and set expectations. It will avoid later (and stronger) disappointments.

Other tweaks to try

The tips above will probably have the most impact on our PhD productivity in the face of task conflict. Depending on our particular situation, we can also get a moderate boost by:

- Managing our energy and attention, not only our time. So far, we have talked about the amount of “time spent” on our priorities and the thesis, not about when that time is spent. As we saw in the chronobiology post, we are not equally effective at all times of the day. Therefore, if we can shuffle around the timeblocks of our different projects/priorities, it pays to move our thesis work to the times when we are most productive and focused. For instance, I try to do my deep research-related work in the mornings, which is my high-focus, high-energy time.

- What is done first… is done for sure. This is a corollary of the previous one. Our energy, attention, willpower and focus seem to be a finite resource (cf. the notion of “decision fatigue”). Hence, if we find that important thesis tasks are difficult (as they often are), doing them first may be our only way of ensuring that they are done at all. This is also called “granny’s rule” in some circles, from the ancient custom of grandmothers to have children eat their carrots before they have a right to eat their dessert. So wise, grandma. Get into the habit of doing the most important (not necessarily the most urgent!) thesis tasks before doing anything else. How to recognize these tasks among our overflowing to-do list? The tasks that we keep postponing, the ones that make us uneasy because we are not sure how (or if) we can pull them off… those are often the most important. But we can also double-check with our supervisor!

- Balance regularity and length/depth. Timeblock planning incorporates the assumption that one needs an amount of uninterrupted time to make progress on something (especially if it is hard). Thus, when timeblock planning, we must be aware of the length of the blocks we assign to the thesis. I’d say 60 to 90 minutes is the bare minimum needed to get a difficult research task into my head. More often, 2-3 hour blocks are needed to make noticeable progress in them. Thus, we can try to target those block lengths when planning our thesis work. What happens if those long blocks are rare, and we do not have a lot of control over our schedule? Then we hit another problem: regularity. The more time it passes between one thesis-work block and the next one, the harder it will be to bring all the needed concepts and ideas to mind and make actual progress. Conversely, when we work on a set of ideas for a long time several days in a row, it becomes effortless to get “into the task”. We may have to balance regularity and depth, e.g., making sure we have at least one longer block of thesis work a day, for as many days in the week as possible. In this sense, having regular times for our thesis work (“every day at 10am is thesis time!") may also help, if we can organize our schedule that way.

- Use physical reminders to quickly load the thesis context. Related to the previous one, we can exploit particular physical artifacts and visualizations to make the “thesis context loading” faster. We could have a card with the main research question of our thesis or latest study, visible on our desk (similar to our Monday mantras). Or we could keep a printed copy of our most current thesis CQOCE diagram in our backpack, so that we can take a look at it when we sit at the library for a “thesis timeblock”.

Review. Iterate. Review. Iterate.

One last piece of advice: do not try all the strategies above at the same time! Each of them requires developing one (or more) habits, which may take some weeks to stick and get used to. If we are keeping a journal or diary, we can add a brief note there about whether we stuck to the habit, and what effects we noticed. Then, every 1-2 weeks, we can review whether it worked (hence, we keep the habit), whether we need to implement it in a different way (which is most likely – some habits take several iterations until we make them work for our particular situation). The goal is not to be perfect at productivity from day one (no one is, ever), but rather to be progressively better at it.

That may be the most important part of this post: the incremental improvement mindset. The problems of task conflict are very real, and they are difficult to solve (if they were easy, we would have solved them long ago!). If today we fail, recognize that productivity is a practice, and start again tomorrow. Or start today – just do a pomodoro! “Start again” is the key meta-habit to learn.

NB: In case you are wondering… no, task conflict does not go away after you become a doctor. In most cases, it becomes worse! It is actually a classic problem of academics, and the main reason many professors are unresponsive to our requests – they are just overwhelmed by their different jobs and responsibilities. That is why it is very good to start learning how to deal with task conflict in your life, today.

Did you try these techniques to overcome task conflict and progress more in your thesis? Did they work? Actually, I’d love to hear pushback against them. Why didn’t they work for you? That will push me to think of new tactics, or improve these ideas so that they work for a wider set of people. Don’t be shy! :)

Image by Matheus Henrique azideiadele from Pixabay

-

The formal length of the thesis in doctoral programs assumes that one works full-time on the thesis (i.e., 40 hours a week or so). Many programs have provisions for “half-load” theses (i.e., 20 hours a week) that take twice as long to complete. Yet, if we can only dedicate 10 hours a week to the thesis, many programs will not accept that we spend, e.g., 4x the time (12? 16 years?) finishing the dissertation. Check your local rules and regulations! ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.