POSTS

Writing exercise: sitting with uncertainty

by Luis P. Prieto, - 7 minutes read - 1363 wordsHave you ever had this feeling, while writing, that your prose is leading nowhere? that right now it would be a great moment to defreeze the fridge? to check your phone, because someone may have texted? In this post, I offer a simple exercise to use next time these internal interruptions assail you during writing.

Last week I attended a “writing camp” (or “writing retreat”): a small group of PhD students and supervisors got together for a few days, away from the office, to get some research writing done. Most of the time, we were sitting in the same room, doing “group pomodoros”. That was it. Just writing, together. The effects of applying a bit of social pressure and focus techniques on my writing productivity were considerable. But I hear it is even more dramatic for those with jobs, kids and other strong obligations beyond their research.

Interrupting oneself

Still, the paper I’m currently writing was not finished during the writing camp. Hence, I’ve spent the last few days trying to reproduce that level of productivity on my own… with appalling results. Paradoxically, the problem has not been that I was being constantly interrupted by others. More often than not, I was interrupting myself! Here’s a typical example of my internal monologue:

(… 8 minutes into a pomodoro…)

– This related work section looks flimsy

– Yep. Only 10 references? In this high-impact journal they are going to laugh at us

– Look, laptop battery is at 23%, we better get up and plug it to the AC

– Coming back to the related work…

– Hey, just remembered, we have to book the badminton court for Sunday!

(etc., etc.)

It turns out, this is a very common experience (called “internal interruption” or “self-interruption”1), especially when we do boring tasks or we have low energy levels. Yet, in this case I am writing about a topic that I think is important, about a study whose findings I find exciting! What’s going on here?

Apparently, this kind of self-interruption happens when our brains re-assess the current strategy, and whether it is likely to meet our goals1,2. Imagine how our hunter-gatherer ancestors thought twice before running after some deer for today’s meal (is foraging for berries more likely to be successful?). Similarly, our brains are doubting whether to continue writing is a good strategy (maybe they will reject the paper after all, and I will feel bad), or whether other strategies will take us closer to our goals (seeing a text from a friend will signal that I am loved, and I will feel good). In summary:

It just feels uncomfortable not to know how things will turn out.

The problem is, our brains seem to ignore several things that research has now evidence for: that this kind of interruption (and multi-tasking in general) can damage our performance in difficult tasks3; that chronic multitaskers seem to do worse in analytical writing tasks4; or that just the fact of having a distractor (like our smartphone) nearby, already triggers some of this multi-tasking and self-interruptions5.

What can we do when these self-interruptions assault us during writing (or any other difficult task that requires focus)?

An exercise on sitting with uncertainty

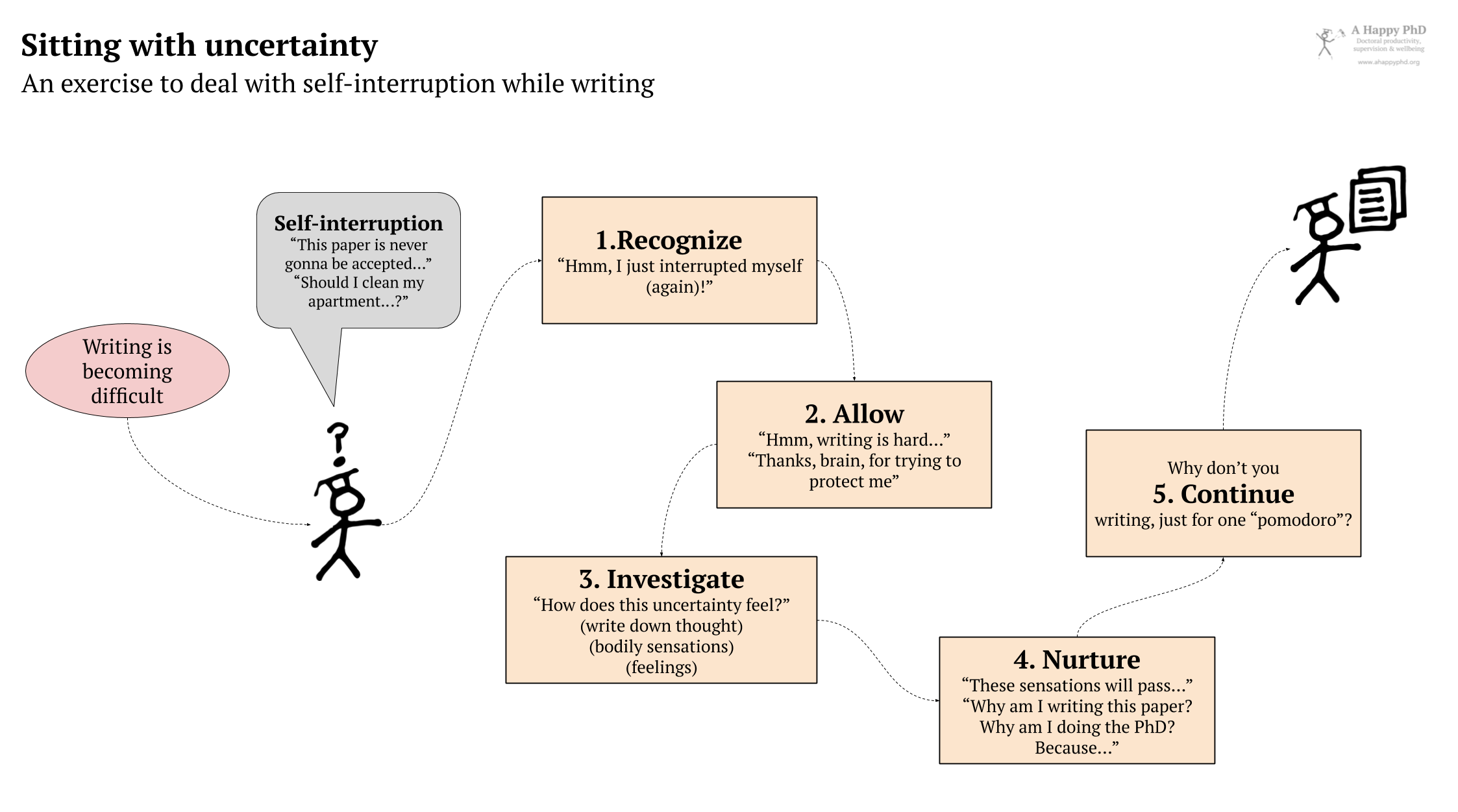

Next time you are writing and you catch yourself doubting whether your prose is good enough, whether the effort is worth it, try the following:

- Recognize. You caught yourself doubting, so you are already in step 1. Simply recognize that you were feeling uncertainty about where this is going, not with the whiplash of guilt (you dumb brain!), but rather with gentle curiosity (hmm, how odd!).

- Allow. Do not force your attention back to writing right away. Do not dismiss your doubts (writing is difficult and uncertain). Allow the feelings of doubt, of uncertainty, to be there. You could even thank your brain for trying to protect you from “danger” or “failure”.

- Investigate. For a minute or two, try to delve into the feeling of doubt, of uncertainty. Close your eyes for a moment. Hear your thoughts, what do they say exactly? You can write them down if you have a piece of paper at hand (“this related work looks flimsy”). Turn your attention to your body, do a quick scan: how does the uncertainty feel? pressure in the forehead? a knot in the stomach? a feeling of low energy? or high-energy restlessness? Do the sensations change as you observe them? Do not reject any of these sensations, just recognize each of them with curiosity (hmm, interesting!).

- Nurture (others call it Non-Identification). Now that you know what this moment of uncertainty is made of (your brain thinking thoughts, the swirl of body sensations and feelings), you can see that this is not who you are. These are just experiences that happen spontaneously, like an itch, and eventually go away. And these particular sensations tend to happen when we do difficult things… like writing. Now is a good moment to connect with your why: why are you writing the paper? what is your purpose? I don’t mean obvious things like “to get a PhD”… why is the PhD important to you? will it bring a better livelihood to your family? will it help you understand the world better? gain new and exciting skills? will the ideas in your paper help others? Bring to your mind all the wonderful things that will come through you writing this paper.

- Continue. Now, ask yourself this simple question: what would happen if you continued writing for just one pomodoro? (or until the end of the current one). Why don’t you try and see what happens? After that period of focus ends, give yourself permission to stretch, defreeze the fridge, or do whatever you want (although it is a good idea to get some “real rest”, be it napping, water breathing, or meditating6).

Even if it took you a while to read the steps above, the whole exercise does not need to take up more than a couple of minutes. You can use the initials (RAIN… and continue) as mnemonic aid to remember the steps. In case you’re curious, the exercise is an adaptation of well-known exercises in certain Buddhist traditions and psychotherapy approaches7. There is even a neurology base to this kind of sequence for learning new difficult skills6.

This exercise has helped me get through these past days of solitary, self-interrupted writing, until I have finished the first draft of my paper (yay!). I hope it helps you as well.

Give it a try the next time you are writing a paper… and let us know how it worked for you, in the comments section below!

Header image by Pikrepo.

-

Adler, R. F., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2013). Self-interruptions in discretionary multitasking. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1441–1449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.040 ↩︎

-

Seipp, A.-K. (2019). Why do we keep interrupting ourselves? Exploring the reasons for internal interruptions at work. Performance Enhancement & Health, 7(1–2), 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peh.2019.100148 ↩︎

-

Adler, R. F., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2015). The Effects of Task Difficulty and Multitasking on Performance. Interacting with Computers, 27(4), 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1093/iwc/iwu005 ↩︎

-

Lottridge, D. M., Rosakranse, C., Oh, C. S., Westwood, S. J., Baldoni, K. A., Mann, A. S., & Nass, C. I. (2015). The Effects of Chronic Multitasking on Analytical Writing. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’15, 2967–2970. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702367 ↩︎

-

Ward, A. F., Duke, K., Gneezy, A., & Bos, M. W. (2017). Brain drain: The mere presence of one’s own smartphone reduces available cognitive capacity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 140–154. ↩︎

-

See this long Joe Rogan podcast with neurobiology professor Andrew Huberman. They talk, e.g., about how to dose rest after periods of deep focus, or how the dopamine that we produce when thinking about our purpose (i.e., that this is the right thing to do) helps buffer the energy we use when focusing for a long time on difficult stuff. ↩︎

-

In this podcast (about 32:45 minutes in), they mention how most of therapy is just “notice it, sit with it, put it in perspective”. See also, e.g., this other post. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.