POSTS

Breathing through the PhD: Breathwork in the doctorate

by Luis P. Prieto, - 13 minutes read - 2756 wordsDuring the doctorate (and in our later lives as researchers) we have to deal with a wide variety of situations and tasks, some stressful, some requiring focus or calmness. Going to therapy, doing therapy-inspired reflection exercises, journaling, and other practices are all very useful, but they require us to step away from the difficult situation. If only there was a simple, free, portable tool to help us in such situations, something we could do in any occasion and which is evidence-based… Wait, there is! This post is about breathwork, an array of tools with an increasing body of scientific evidence demonstrating its effectiveness. The post describes how we should breathe for better health and cognitive performance, and how different kinds of breathing patterns can help us cope with common challenging situations throughout the PhD.

We breathe about 22,000 times every day, yet we seldom think about how we breathe. Our breathing not only provides the oxygen our cells need to perform their basic functions (i.e., it is our most basic fuel!), it is also connected with many other bodily processes neurologically, chemically, and mechanically. Contrary to other automatic processes like heartbeat, however, we can voluntarily modulate our breathing – and that allows us to influence in turn many aspects of our body and mind through these connections. This has been known (and exploited) for centuries by ancient traditions like yoga or Buddhism… but now there are more and more scientific studies quantifying and comparing the advantages of these practices with other tools.

I cannot think of any other tool that is cheaper (as in, free), more portable and easier to integrate in our daily life than breathwork. No pills, no equipment, nothing else needed other than our own bodies. Below are a few basic notes on breathing and breathwork exercises and patterns I have discovered in my on-and-off dive about the topic for the past year or so. In case you are interested in a deeper dive, there are now more and more popular nonfiction books describing both the ancient traditions and the modern science of breathing, such as James Nestor’s Breath1… and you can of course read the scientific papers I cite throughout the text.

How to breathe (in general)

Nestor’s book describes at great length how we (modern humans) have become one of the worst breathers in the animal kingdom, in part due to environmental forces our genes have not yet had time to adapt to: chronic stress, postural issues (i.e., sitting all day), or a general lack of attention to our body sensations.

How should we breathe instead for better health and (mental and physical) performance? Of course, our breath should adapt to the situation at hand (running for the bus and writing a paper abstract have very different oxygen demands), but in general we should breathe…

- … through our nose (unless doing strenuous physical exercise), since mouth breathing is associated with a plethora of disadvantages, from higher anxiety and more respiratory infections to bad dentoskeletal development.

- … emphasizing the exhale more. Ensuring that we empty our lungs completely (e.g., by making the exhales a bit longer than the inhales) not only leads to a slightly more relaxed state (as shown in many of the specific practices mentioned below), it also helps new oxygen to come in our lungs, to our blood and our cells.

- … slower. There are also studies linking different health conditions (and longevity) to our respiratory rate (i.e., how often we breathe), probably because rapid breathing leads to insufficient carbon dioxide in the blood which in turn hampers oxygen exchange at our cells. Drawing from different studies and sources, Nestor suggests that the “ideal breath” takes 5.5 seconds to inhale and 5.5 seconds to exhale (which adds up to 5.5 breaths a minute – spooky!).

- … less forcefully (i.e., more shallowly) than we normally do. When we exercise (and/or have an asthma attack), we tend to take big gulps of air, as our bodies try to keep up with the increasing oxygen demands (or lack of oxygen supply, in the asthma case). Apparently this natural strategy is not very successful: more shallow, silent breaths in which the diaphragm and the whole ribcage circumference are involved, get more oxygen into our lungs and blood.

Just paying attention at random times how we breath (e.g., by setting a timer and checking) and reminding ourselves to do it more slowly and shallowly through the nose (and emphasizing a bit the out breath), is likely to have a small but positive effect in our long-term health – wether we are already healthy2 or suffering from a variety of health conditions3. However, don’t expect to reach such low respiratory rates at first! These ways of breathing (and the concrete exercises below) take some time to develop. That is why we said it is a practice.

One breathwork for every occasion

Given that breath is directly or indirectly linked to multiple physiological (and brain) functions, we can use specific breathing patterns to help us cope with different kinds of situations and demands. These patterns often come from ancient practices like yoga, but have now been studied by modern science as well. As mentioned above, some of these exercises may not be doable or easy if you are a total breathwork newbie. Also, please take basic safety into account (always try these first in a safe place and position, and don’t drive or do other hazardous activities while you try them).

Breathing for focus and vigor: Some breathing patterns can help activate the sympathetic nervous system, creating a sense of alertness and/or pumping up our heart rate. This can be helpful if we are getting sleepy but we need to work on a paper (e.g., in the morning)… or if we are about to engage in some physical activity. You can try:

- Prolonged exhales, more concretely inhaling to the count of 2 and exhaling to the count of 8 (adding up to about 6 breaths per minute), have been shown to reduce stress response but allow resources (especially mental resources) for “active coping”, i.e., when we are stressed but also need to perform a task while enduring the stress4.

- Alternate nostril yoga is a classic breathing technique (you can find plenty of videos teaching you to do this online) in which one alternately blocks one (nasal) airway to inhale through the other one, and viceversa. Although this exercise is often advertised as good for stress relieving, it has also been shown that 15 minutes of this exercise can increase our alertness and vigilance, thus helping us fight drowsiness and distraction5.

- Coffee breathing (as named in Lucas Rockwood’s nice TED talk on breathwork) consists on taking about 20 sharp but relaxed exhales in a row, through the nose (and then, breathing normally for a while to rest, and then doing another two rounds of that). This is another technique that I have tested myself and seems to work quite well to pump me up in the morning, heat up when feeling cold, or get ready before exercising. While I haven’t found studies testing its effectiveness in a systematic way, it seems quite similar to the “cyclic hyperventilation” that some studies show can activate our sympathetic nervous system6.

Breathing to stay calm is another common use case for breathwork. Maybe we are nervous because we are about to present our work in front of a bunch of critical experts (something every PhD student does at conferences or their thesis defense), and we need to calm down. Maybe our paper or proposal just got rejected and we want to be in a colder mood before deciding what to do or writing a response email. A couple of breathwork practices could be helpful here:

- Tactical beathing (TB), sometimes also called “box breathing”, requires us to inhale to the count of 4 (preferably, engaging our belly, i.e., our diaphragm), hold our breath for 4 seconds, exhale to the count of 4, and hold our breath again for 4 seconds (and repeating this cycle for 5-15 minutes). This technique is widely used in the armed forces, law enforcement and emergency response teams to lower down stress responses, and seems especially useful when we can take some time to do “passive coping” (i.e., calming down without having to do any complex mental tasks at the same time)4.

- As mentioned above, you can also try the alternate nostril yoga exercises as a stress relieving practice, especially if you have the time and space to be on your own (this practice is a bit conspicuous as it requires you to use your hands to block the nose – which may look weird for people unfamiliar with yoga).

Breathing to improve our mood and fight depression, anxiety or stress. In this blog we have talked a lot about the commonality of emotional symptoms among doctoral students (e.g., stress, depression, anxiety). It turns out that breathwork has also been shown to help with many of these emotional ailments, especially when practiced regularly (e.g., 5 minutes every day, for a month7). Of course, breathwork is more likely to work with milder versions of these emotional disorders, while deeper problems will require more involved interventions and professional help. Yet, given the low effort and cost involved in breathwork, it is worth trying as a complementary strategy to whatever else we’re doing to fight emotional distress!

- Slow breathing in general (i.e., most of the patterns mentioned above, which will require you to do slower, more regular breaths) has been shown to help with a variety of mood disorders8, and some studies show improvements regardless of the specific pattern people engaged in7. Yet, if you have a specific emotional response that is problematic for you, you can try the following suggestions…

- Coherent breathing consists of slow, gentle breaths of equal inhale and exhale duration, starting at 4 seconds each and slowly progressing towards 6-second inhales and 6-second exhales (as we get comfortable with this pattern of breathing). This pattern seems to be particularly effective at staving depressive symptoms9, but may also help with other mood disorders.

- A recent study found that physiological sighing (taking two in-breaths to fill our lungs fully, and then exhaling through our nose to empty our lungs completely – see a demonstration in this video), done for 5 minutes a day, was the most effective breathing pattern to improve anxiety symptoms and improve mood7.

- If your primary emotional problems is stress, then you can try slow diaphragmatic breathing (breathing slowly, engaging primarily the belly/diaphragm, so that both the inhales and exhales are done in a controlled manner), which has shown measurable effects in cortisol (the main stress hormone), affect and attention, when done for 15 minutes a day, over 8 weeks10.

Breathing to rest, recover, and relax. Sometimes, after a long day at the lab or in a conference, our head keeps spinning and spinning, and it is hard for us to just relax and drift into unconsciousness. There are several breathing patterns that we can use to help us relax our bodies and minds:

- In general, breathwork with extended exhales (i.e., where the exhale lasts for longer than the inhale) tends to have a calming or relaxing effect, as it tends to lower our heart rate and engage the parasympathetic nervious system. For instance, I have come to the habit of using the “Whiskey breathing” exercise mentioned by Lucas Rockwood, as the last thing I do when closing my eyes in bed. It has worked wonders on how fast I fall sleep (but maybe sleep deprivation due to new parenthood is also playing a role there).

- Similarly, multiple studies have noted that slow breathing (across its many forms, see above) has a soothing effect that affects not only mood but also physiology8, thus helping us relax, be it for a 5-minute break or an 8-hour night of sleep.

Breathing… pretty much anytime. As noted above, we tend to breath faster and more irregularly than we probably should in most of the situations we experience. Thus, engaging in a balanced, more regular and slower breathing pattern (but not too slow, lest we over-relax and fall into drowsiness) such as Rockwood’s “water breathing”, whenever we remember or just feel like it, is probably a good idea. For instance, I often do that breathing pattern during longer drives, and it both feels good and makes the trip feel shorter.

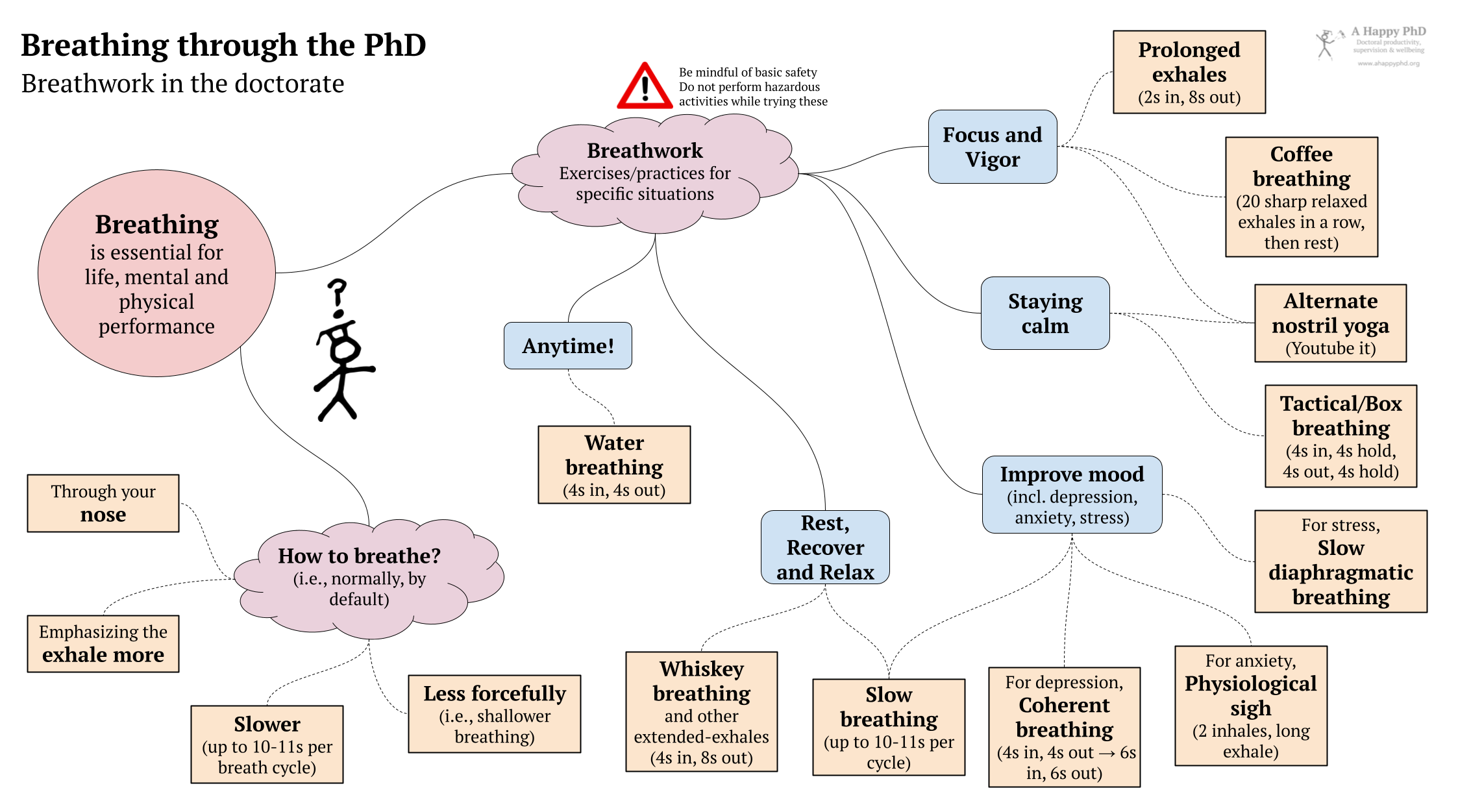

The diagram below summarizes the different ideas and exercises featured in this post:

The big takeaway

After reading this long list of patterns and exercises, one notices a lot of overlap. Indeed, if there is one message I would like you to take from this post, it is that doing structured breathwork practices is probably going to be beneficial, regardless of what specific pattern you try7. The options above are just starting points studied by science. Choose one that feels comfortable (or slightly uncomfortable, you will get used to it with practice) and relevant to your situation – and do it, both episodically (when facing a specific challenge) and regularly. Don’t expect the effects to be miraculous or instantaneous (as effect sizes for these interventions are probably small2), but they will probably be noticeable, if you pay attention. Indeed, that could be a second key idea to take away: pay a bit more attention to how you breath, and correct it when needed. This attention to breath is a nice mental exercise, and one of the basic pillars of other useful tools like mindfulness meditation.

Now, take a breath…

Did you try any of the breathwork exercises listed above? Did they work? Do you have other breathing exercises you have found useful, or breathwork-related research you found interesting? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header image by Ralph using MidJourney.

-

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The new science of a lost art. Penguin UK. If you have time to spare, it is also interesting to see some of the videos the author has compiled with additional explanations and breathing exercises (e.g., I have now used the ‘nose unblocking’ exercise quite a few times during last Fall’s kindergarten-induced viral/cold season). ↩︎

-

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., Borges, U., Dosseville, F., Hosang, T. J., Iskra, M., Mosley, E., Salvotti, C., Spolverato, L., Zammit, N., & Javelle, F. (2022). Effects of voluntary slow breathing on heart rate and heart rate variability: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 138, 104711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104711 ↩︎

-

Jayawardena, R., Ranasinghe, P., Ranawaka, H., Gamage, N., Dissanayake, D., & Misra, A. (2020). Exploring the therapeutic benefits of Pranayama (yogic breathing): A systematic review. International Journal of Yoga, 13(2), 99. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_37_19 ↩︎

-

Röttger, S., Theobald, D. A., Abendroth, J., & Jacobsen, T. (2021). The Effectiveness of Combat Tactical Breathing as Compared with Prolonged Exhalation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09485-w ↩︎

-

Telles, S., Verma, S., Sharma, S. K., Gupta, R. K., & Balkrishna, A. (2017). Alternate-Nostril Yoga Breathing Reduced Blood Pressure While Increasing Performance in a Vigilance Test. Medical Science Monitor Basic Research, 23, 392–398. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSMBR.906502 ↩︎

-

Kox, M., Van Eijk, L. T., Zwaag, J., Van Den Wildenberg, J., Sweep, F. C. G. J., Van Der Hoeven, J. G., & Pickkers, P. (2014). Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(20), 7379–7384. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1322174111 ↩︎

-

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., & Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 100895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895 ↩︎

-

Zaccaro, A., Piarulli, A., Laurino, M., Garbella, E., Menicucci, D., Neri, B., & Gemignani, A. (2018). How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353 ↩︎

-

Streeter, C. C., Gerbarg, P. L., Whitfield, T. H., Owen, L., Johnston, J., Silveri, M. M., Gensler, M., Faulkner, C. L., Mann, C., Wixted, M., Hernon, A. M., Nyer, M. B., Brown, E. R. P., & Jensen, J. E. (2017). Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder with Iyengar Yoga and Coherent Breathing: A Randomized Controlled Dosing Study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23(3), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2016.0140 ↩︎

-

Ma, X., Yue, Z.-Q., Gong, Z.-Q., Zhang, H., Duan, N.-Y., Shi, Y.-T., Wei, G.-X., & Li, Y.-F. (2017). The Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing on Attention, Negative Affect and Stress in Healthy Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 874. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874 ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.