POSTS

Four scheduling strategies of successful PhD students (book extract)

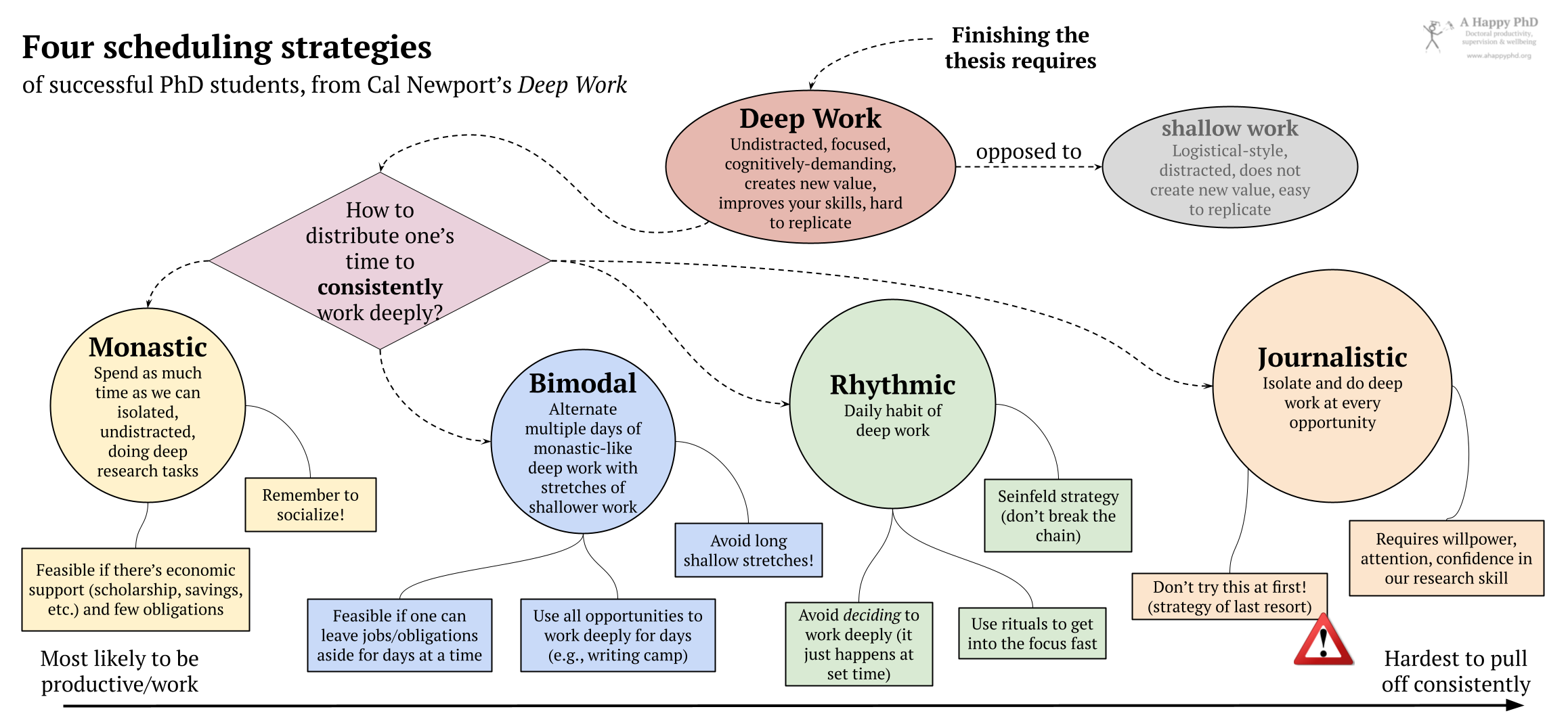

by Luis P. Prieto, - 10 minutes read - 2019 wordsThe ability to concentrate and do focused, cognitively-demanding work is crucial to finishing a PhD (and doing research in general). Yet, we often spend our days in emails, meetings and other busywork that does not bring us closer to completing our goal (e.g., the thesis!). How to keep the busyness at bay so that we dedicate more time to the important stuff? In this post, the first of a series based on Cal Newport’s classic book Deep Work, we look at the high-level shape of a deep-worker’s calendar. What are the strategies that doctoral students have successfully used to find time to advance in producing their thesis materials?

Deep Work?

The main premise of the book is quite simple (what Newport calls his “Deep Work Hypothesis”). He argues that the ability to perform deep work is becoming increasingly rare and valuable in our (knowledge) economy. Thus, the few who cultivate this skill and make it the center of their working life, will thrive.

But let’s define deep work (and its opposite, shallow work) first. These are the definitions given in the book1:

Deep Work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.

Shallow Work: Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.

These two categories look distinct on the surface, but deciding whether our (PhD) tasks are deep or shallow may not be straightforward. Is this meeting with my supervisors deep work? the very important email about setting up my study participants? Newport provides a question to help us decide which bucket to put tasks in: “how long would it take (in months) to train a smart recent college graduate with no specialized training in my field to complete this task?".

In research, those activities that ultimately generate value (i.e., our contributions to knowledge) will be, almost by definition, deep work: designing an astute experimental protocol for a study, synthesizing and connecting research papers in a literature review, deciding which analysis method to apply to our data, and performing the analyses correctly and systematically… all are deep work.

However, this is not to say that 100% of our work hours should be deep. Indeed, Newport himself posits that the brain’s capacity for deep work is limited. Depending on the kind of deep work one does, four hours a day is a common sustainable quantity; six hours a day is already rare. But the key to great deep work achievements is consistency. Can we make deep work a habit?

In my work with doctoral students (and my own doctoral period), I have seen many students that get stalled or blocked… but very rarely due to lazyness. More common is the PhD student that does not advance due to overwork… of the wrong kind of work. Too much shallow (or even deep!) admin work on thesis-unrelated projects, jobs or obligations. Conversely, students that manage to consistently make space in their calendars for deep work on the thesis materials seem to breeze through the doctorate. But how do we do that? One key underlying point in the book is that deep work takes time to get into (even if there are tricks, like rituals, to somewhat speed up this transition to deep work). Thus, not every way we organize our time and attention will be useful to carry out the considerable amounts of deep work required by a doctoral dissertation. Especially, haphazard, ad-hoc strategies defined by random external pressures on us, are likely to fail. What deep work scheduling strategies do work, then?

Scheduling Deep (probably Creative) Work

As we have seen, doing deep research tasks (e.g., study design, data analysis, reading and synthesizing) consistently is what “moves the needle” in a doctoral dissertation. However, every person’s circumstances are different: people have families, obligations, side jobs or interests, which can make the consistent and prolonged engagement in deep dissertation work difficult. Thus, if you can organize your life in a way that creates long, regular stretches of uninterrupted time for the thesis, do it (environment often trumps willpower!). If that’s not an option, there are multiple paths to deep work success, as documented by Newport (and my own observation of effective doctoral students):

-

The Monastic strategy: Monastic PhD students have identified the most important, high-value parts of their work and just spend quite a few hours every day away from distractions, doing such deep research work. This strategy is simple: eliminate or radically minimize shallow work, obligations and distractions, so that every day is filled with deep dissertation work. As an example, I can give the first 1-2 years of my own doctoral process. I had quit my job in the industry and was living off savings; I had no children or dependents. Thus, every day I had all the time I wanted to read scholarly papers, do fieldwork related to my thesis topic, etc. Since my desk was in a lab’s open floor space (with many other people and frequent interruptions), I got on the habit of frequently going to one of the university libraries (a beautiful, historic building) for long periods of time when concentration was needed. Yet, I was not completely monastic (social support and connection are important positive factors to avoid mental health troubles): I still came back to the lab for coffee breaks, joint workouts (e.g., frontón matches), etc. I remember this period as one of the happiest of my life, a perfect balance (for my taste) between isolated focus and socialization. If you have a scholarship or other means of covering your economic needs and you have few obligations, I strongly recommend this strategy. But not everyone’s life (or PhD work) is amenable to this clarity and reclusiveness…

-

The Bimodal strategy: Bimodalists alternate between deep, focused stretches of time (Cal notes, at least one full day) and other stretches that are more open to necessary shallow work, communication, and external inputs. We could also call this the “part-time monastic” strategy. One caveat: one probably should not spend a long time away from the thesis, as putting such a complex set of ideas and problems back again in one’s head will take some time (an overhead the monastic student does not incur). This strategy is especially useful for PhDs that work in teams, or in projects that necessarily involve collaboration. One doctoral student I know is a great example of this strategy. She has many obligations (professional and family-related) aside from her doctoral studies. However, she makes use of every opportunity her university offers for stretches of several days focusing deeply into her research, paper writing, etc. She has attended (and organized) more doctoral “writing camps” (including unofficial meetups with fellow bimodalist PhD students) and research stays than any other student I know… This is not out of fancy, but rather out of necessity to get her research and publications done (while maintaining a family and another job). This strategy works as long as we can leave those other obligations aside for some days at a time (e.g., someone to cover up for childcare on the days of a deep focus stretch). But, what if we don’t have the chance for such long stretches of seclusion and focus? what if we have to take care of kids or a job every day? We then resort to…

-

The Rhythmic strategy: Create a daily habit (a ritual, even) of deep work (as in, undistractedly working for, at least, 90 minutes on our hard research stuff) and focusing on following this habit consistently. To keep ourselves motivated for this consistency, we could use tricks like the “Seinfeld strategy”, marking in a physical calendar every day we manage to follow our deep work ritual and aiming for (and tracking as a big number on top of it) the longest uninterrupted chain of days we did it. The key to pull this strategy off is not making the decision to work deeply – deep work is just something that happens every day at X appointed time. Full stop. Newport himself provides an example of a doctoral student using this strategy. Brian Chappell was a PhD student who became a father and decided to take on a university job while doing the thesis. After failing to put 90-min chunks ad-hoc during the day whenever he had time between family and his full-time job (the chunks just ended up not happening), he settled into waking up at 5:30am, working on the dissertation for two hours and then preparing breakfast and going to work with the dissertation work for the day already done (thus qualifying for a great application of “granny’s rule” as well). Using this scheme, he finished writing his dissertation (which he had been working on for more than a year unsuccessfully) in a few months. But what if our life is so complicated that we cannot pull off this strategy either?

-

The Journalistic strategy: Named after the fact that some journalists use it to get their writing done on very tight deadlines, this strategy consists on shifting into deep work whenever you have some time and opportunity. By “shifting into deep work” I mean to seclude ourselves physically: close the door, shut away distractions, and type (or do whatever it is) furiously for an hour or two. This strategy is by far the trickiest to pull off, as it relies on our willpower and attention (which we know are scarce resources) to do this shift from normal activity to deep research work. Also, it requires a certain level of competence (or confidence) at the kind of deep work we need to do: a lack of confidence in the success of a task is related with procrastination (we will find reasons to not do the deep work). Lack of confidence will also undermine concentration, leading to self-interruptions even if we shut ourselves away (see this post for a technique to counter such impulses). Since PhD students are, almost by definition, novices at many research tasks, I do not recommend to try this strategy, unless the others above are impossible or have failed unequivocally. This one is the strategy of last resort. Looking for an example, I have to admit that no PhD student comes to mind that used this as her main strategy (but I don’t know that many doctoral students). This is, however, the strategy that I find myself trying to implement currently, as a researcher and recent parent. Even if I’m quite confident as a researcher, my productivity so far has not been great. Tips that I have found useful so far include:

- Have a clear plan for what is the deep task we will work on (e.g., “this week I’ll work deeply on outlining and referencing my next journal paper”).

- Have the “deep task” ready at a moment’s notice, to make the transition to deep work as smooth as possible. I use a different workspace in my laptop to have my deep work task open in full screen mode, which I can switch to with a single keystroke.

- Do not multitask. If we are caring for a child that is awake (or taking a short nap), we are not using our deep, uninterrupted focus. The quality of the resulting work will show it.

- When shutting ourselves off for deep work, leave our smartphone out of the room.

The image below summarizes these four scheduling strategies:

What will your path to deep doctoral success be?

Did you try any of these strategies? Did they work? Do you have other overall strategies you use to consistently get your deep research work done? Have you successfully applied a journalistic strategy as a doctoral student? How did you do it? Let us know in the comments section below, or leave us a voice message!

Header image by rawpixel.com from PxHere.

-

Newport, C. (2016). Deep work: Rules for focused success in a distracted world. Hachette UK. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.