POSTS

Chronobiology addendum: A neurobiologist's guide to a healthy and productive day

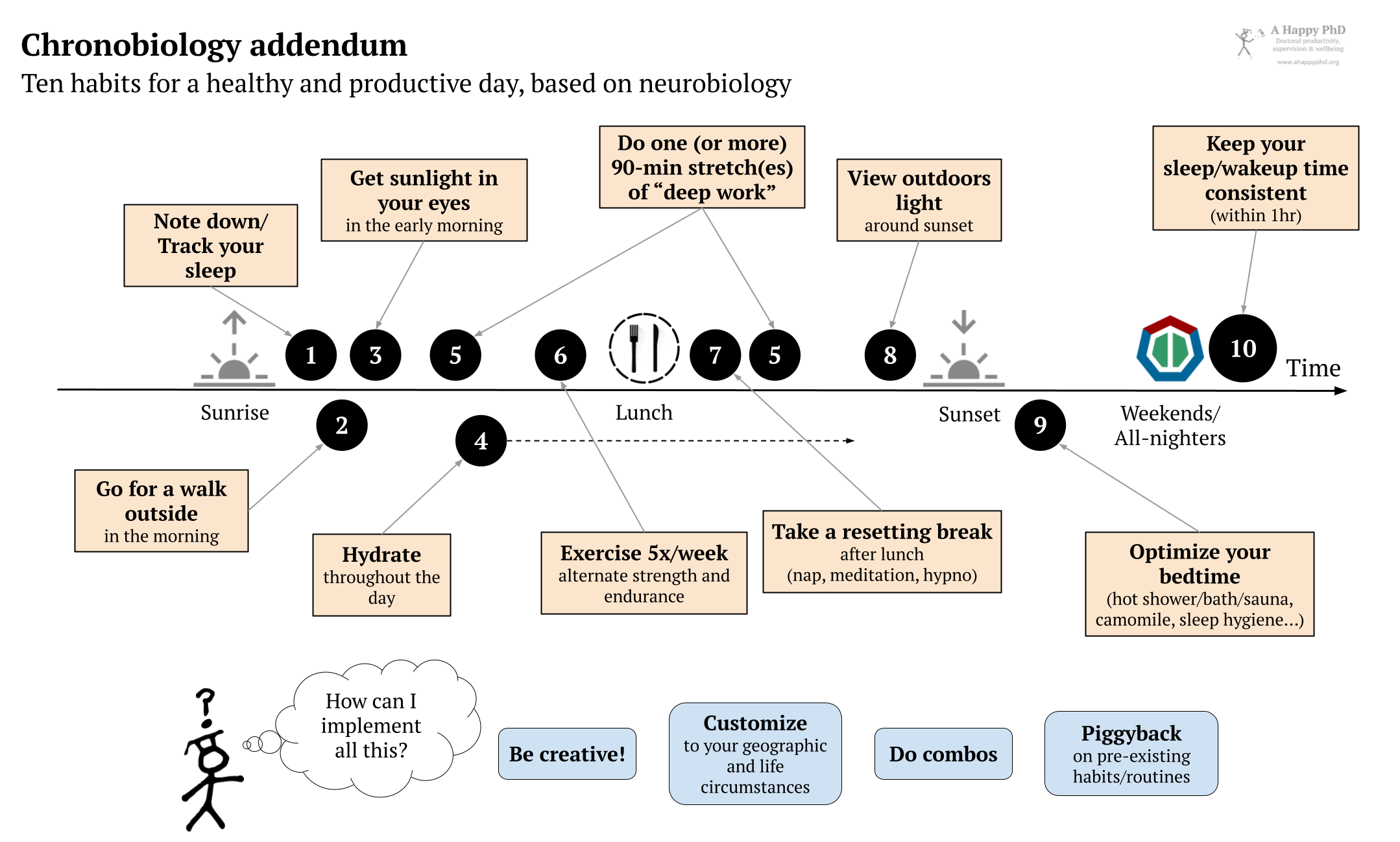

by Luis P. Prieto, - 14 minutes read - 2812 wordsIn previous posts, we have seen how chronotype can influence our productivity, and how we can tweak our breaks to make the most of the ebbs and flows of our daily energy. But, how exactly can we use this chronobiology knowledge to craft a daily routine that is both productive and healthy, and fitting to our particular situation? In this post, I borrow from the habits and routines of an expert on the topic (Stanford neurobiologist Andrew Huberman) ten easy protocols you can put in practice to make every day your best day.

As you may have guessed if you have read the blog for some time, I am fascinated with how we humans work. One thing that always surprises me is how, some days, my energy, my concentration levels and humor are so high that everything feels effortless; and others, it’s like swimming in molasses (and, sometimes, both feelings come on the same day!). Fortunately, the more I learn about research on chronobiology and the physiology of sleep, the more these variations start making sense. Yet, there is so much research (and non-evidence-based advice!) out there, that I am oftentimes confused about what to implement in my own life. How to prioritize health and cognitive outcomes, but also have enough time to do what is important for us (like finishing that godd%&$%d paper)? Aren’t there any cheap, simple, time-efficient actions we can take quickly, and get on with our day?

I was trying to build up such a catalogue of habits and advice by myself, through a lot of reading (and a lot of haphazard trial and error)… when I came across this podcast episode from the Huberman Lab. Andrew Huberman is a neurobiology and ophtalmology professor at Stanford, who shares some of the same interests. In this episode, he put together 17 daily habits (what he calls “protocols”), which he uses at specific times throughout his day to stay both healthy and effective. Since he is a (quite productive) researcher, I figured many of these habits would also work for me, and for any doctoral students or more senior researchers reading this.

If you have two hours and would like the full nerdy detail of the 17 protocols and why they work, I heartily recommend hearing the full podcast episode. If you want a quick (and partial) summary you can implement right away, you can just read on below.

I have selected the ten habits I think could be most generalizable to PhD students and researchers across the board. I shied away from nutrition or supplementation advice, whose effects probably depend a lot on your genetics, particular situation, history… and especially, on your target/goals (what is each of us trying to “optimize” for? longevity? weight loss? cognitive performance? at what costs?). In this sense, these protocols have been selected by Huberman according to his goals (which seem to value more work productivity than, say, physical performance), and circumstances (he is apparently single and, as an academic, he has certain freedom of schedule). Your circumstances will certainly be different, so not all habits may fit you. But they seem good starting points to try out and assess for yourself.

Ten science-backed habits for a healthy and productive day

- Note down your waking time… or, more generally, track (roughly) your sleep (Huberman’s Protocol #1). This one is part of my journaling and habit tracking practice, which I do “old school” in a piece of paper. Along with knowing your approximate sleep time, this will let you know how much sleep you are getting. Let’s remember, lack of sleep is behind many of PhD students’ ailments, from poor productivity to depression). Thus, knowing how much you sleep can be a first step towards tweaking your sleep hygiene habits (or seek professional help, if none of that works). Also, by substracting two hours from your average wakeup time, you can find your temperature minimum, around which most of your REM sleep is happening. You can use this knowledge to shift your body clock (e.g., if you have jetlag or shift work) and do other interesting stuff, if needed.

- Go for a walk in the morning, shortly after you get out of bed (Huberman’s Protocol #2). This practice (apparently called “forward ambulation” in the literature), and the “optic flow” of images and eye movements it generates, seems to be very effective in lowering the activity of the brain’s amygdala, which in turn leads to lower anxiety and fear1. Huberman uses this to put himself in a state of alertness and focus (without being anxious or stressed). Personally, I used this during the first months of the pandemic lockdowns (by going for a short walk to a nearby park before coming back home to work), and found it a nice way to start working focusedly (see point 5 below). I should bring this back again into my schedule…

- Get natural sunlight on your eyes for 10-30 minutes, early in the morning (Huberman’s Protocol #3). This practice is supposed to increase our alertness (via certain neurons located in our eyes), and sends several other signals to our organs (thus supporting better immune and hormonal function). It also helps us sleep better the next night (by timing melatonin onset). Do this even on cloudy days (maybe make the exposure a bit longer, then) and, if possible, don’t wear sunglasses (but do not look directly into the sun or anything else that is painful!). This habit is especially easy to combine with point 2 above, if you take a walk (or a run) outdoors early in the morning.

- Hydrate! (Huberman’s Protocol #4). We have heard this advice so many times that it may be redundant to say it… But, still, I find that I often forget to take the recommended two- to three-liters of fluids every day (preferably water, but could also be tea, juices, milk…). Further, Huberman adds a bit of salt to his water, on the basis that those minerals are good for neuronal function.

- Do a stretch of deep, focused work early-ish in the morning (Huberman’s Protocol #7). In this blog, we have long touted the benefits of distraction-free stretches of deep work as a way to make the most of our limited time and attention to deal with cognitively-hard tasks like writing or data analysis. Huberman cites work on ultradian cycles2 (the theory that the nervous system works in cycles of activity and recovery, lasting roughly 90 minutes) to suggest that we cannot really focus on a task for more than 90 minutes in a row. He thus uses this first 90-minute stretch to tackle the most important and hard task of the day. Huberman also does (and I heartily recommend) another 90-minute stretch of deep work in the afternoon, just after his nap/break (see point 7 below). Three hours a day of deep, hard work does not seem like a lot… yet, many of us cannot even get that much out of our days. In my experience, if taken seriously, two of these “deep work stretches” can be as effective as much longer periods of “sorta focused” time. But, of course, if you can get 3, or 4, or 5 stretches of focused work done, that’s even better!

- Do physical exercise five times a week (Huberman’s Protocol #8). This practice is not only aims at helping our physical health and longevity; also, exercise has been strongly linked with brain health and cognitive function (because of increased blood flow to the brain and better hormonal health affecting the brain). Huberman often does his exercise just after the (morning) 90-minute cognitive work stretch (point 5 above). He suggests exercise sessions should be 45-60 minutes long (since longer bouts of exercise may provoke excessive release of cortisol). He also suggests to alternate strength (e.g, weights, bodyweight) and endurance training (e.g., running, swimming, cycling, etc.) in a 3+2 ratio: 3 days a week of strength and 2 days of endurance every week (and then, after 12 weeks, switching to 2+3). Personally, I don’t follow these proportions ultra-rigorously, but this kind of rhythm has proven quite sustainable and beneficial for me. I will not go into the exact exercise routines to follow, as there is plenty of advice out there on that, including Huberman’s own take on this (see this other podcast episode and this other one).

- Take a short break to reset sometime after lunch (Huberman’s Protocol #11). This can take the form of a short nap, or what Huberman calls “non-sleep deep rest” (NSDR), a concept that encompasses many different practices and protocols, from meditation or yoga nidra, to hypnosis. In general, these are practices that induce deep relaxation and, in some cases, focus (both of which will be helpful to tackle the second half of the day in full force). Huberman seems particularly fond of hypnosis (not the sketchy, stage type of hypnosis, but rather a sort of semi-meditative focusing exercises for particular purposes like reducing anxiety, pain or even stop smoking) and the Reveri app, based on the research by David Spiegel3. However, I am not sure how much its benefits depend on the person being “susceptible” to hypnosis (a trait for which there are apparently clinical measurement scales4). Personally, I can vouch for the effectiveness of the humble siesta, in the form of a short, less-than-30-min nap, from which I tend to wake up tremendously refreshed and focused. Longtime readers of the blog will also remember that I am a big fan of mindfulness meditation (e.g., body scan or awareness of breathing), which can also be very restorative and focus-supporting. Try different options and see what works best for you: the effects and preferences are bound to vary from person to person. For instance, we probably should avoiding napping if we tend to have trouble falling/staying asleep at night (then, meditation or hypnosis may be a better option). Whatever form it takes, a purposeful break in the early afternoon is probably a good idea, to make the most out of the natural post-prandial slump and continue our day full of energy.

- View (outdoors) evening light to support sleep (Huberman’s Protocol #13). It seems that the mix of light wavelengths we get when we put ourselves somewhere outdoors towards the late afternoon (e.g., going for a walk outside at sunset) helps release melatonin (a hormone that helps us fall asleep) at the right time when we go to bed later on. Apparently, this “sunset light viewing” also helps us avoid some of the bad effects that bright lights late in the evening (including TV and other screens) have for our sleep quality. In any case, do avoid bright lights and screens from 11pm-4am, if you want to have a great night’s sleep!

- Optimize falling and staying asleep (Protocol #15), by taking a hot bath or shower (or sauna) before bed. Paradoxically, these uses of heat help cool our bodies, which is quite critical for falling asleep. Keeping our bedroom dark, cool and quiet (and the other sleep hygiene tips we saw in the post on sleep) will also help us fall (and stay!) asleep. In his podcast, Huberman also discusses certain supplements he takes, but I haven’t found the need to implement that additional layer of help (other than getting the occasional mug of camomile tea before bed, which naturally contains apigenin). In contrast, I can vouch for the beneficial effects of other behavioral tools for sleeping, like particular forms of breathwork (see the “whiskey breathing” in this TED talk) or progressive muscle relaxation, which tend to knock me out quite quickly (and have smaller chances of side effects than pharmacological solutions).

- Do not change your routine too much on weekends and when recovering from a bad night’s sleep or an all-nighter (Huberman’s Protocol #17). Apparently, the disruption to wakeup and sleep times has worse effects than an occasional night of bad sleep. Thys, we should try to keep our wake up time (and morning light viewing, see point 2) quite constant, even on weekends. Even if that means getting a bit less sleep (as also confirmed by sleep expert Matt Walker). The classic habit of sleeping in on the weekends, or going to bed unusually early after an all-nighter, might not be such a good idea. How much shifting is too much? The rule of thumb I’ve read in some of the sleep science literature is to stay below one hour of shift, from one day to the next5.

Implementation tips

How should we use this list of habits? Is it all-or-nothing, or is it OK if we don’t do one of them? My impression is that implementing as many of them as you can, within the flexibility that your particular circumstances allow, will bring benefits. The good news is that these are free tools, and many of them do not really take up that much time. I also like the “bookending” approach they take: they tell you what to do at the beginning and the end of the day, but they leave the rest quite flexible. Other quick tips I’ve come across when trying to put these routines in place, include:

-

Be creative. Although these practices seem very regimented, they can be implemented in many ways, and could probably be meshed into our existing obligations. Do we have to take calls in the afternoon? Why not do it while we walk in the sunset (point 8)? Do we have a balcony at home? Why not do our first stretch of focused work sitting there and getting our sunny dose (points 3 and 5)? Walking our dogs or taking kids to school on foot, instead of going by car (point 2), etc.

-

Customize to geographic and life context. These habits were devised by someone single, living in the temperate climate of California. Use your judgement and change them as needed. For instance, going for a run at midday is probably a bad idea if we are in Spain in the summer, but it might our best bet to get some rays of sun during a winter in Estonia.

-

Do combos, i.e., stack multiple routines so that we do them simultaneously or in rapid succession. For instance, sleep expert Matt Walker combines points 3 (morning sunlight) and 6 (exercise), by getting his exercise in the morning in a gym that faces the sun. I do a triple combo on the days that I run, by doing it first thing in the morning (thus knocking points 2, 3 and 6 in one go!).

-

Piggyback these habits on top of other routines we already do, as a way to remember them and make them stick. For instance, we could put a jug of water in the foyer, close to the place where we leave our keys after a walk, to remember to hydrate (point 4). Or we could leave a post-it (or our walking shoes) next to the journal we write in after the workday, to remind us that we want to go for an evening walk (point 8).

Of course, the usual disclaimers are in order: this post does not constitute healthcare advice (nor am I qualified to give such advice), and it is intended for informational purposes only. If any of the tips and habits above conflict with a pre-existing condition or treatment, or become painful somehow, consult with a healthcare professional. Et cetera. But, for most people, these habits should have wide safety margins.

The diagram below summarizes the tips and habits mentioned in this post. Feel free to use it as a memory aid!

Do you have other habits or routines you do at specific times in the day, to keep yourself focused, energized or healthy? Did you try any of the habits above? Did it have any noticeable effects? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header image by PxHere.

-

de Voogd, L. D., Kanen, J. W., Neville, D. A., Roelofs, K., Fernández, G., & Hermans, E. J. (2018). Eye-Movement Intervention Enhances Extinction via Amygdala Deactivation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38(40), 8694–8706. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-18.2018 ↩︎

-

Kleitman, N. (1982). Basic Rest-Activity Cycle—22 Years Later. Sleep, 5(4), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/5.4.311 ↩︎

-

See, for example, Jiang, H., White, M. P., Greicius, M. D., Waelde, L. C., & Spiegel, D. (2016). Brain Activity and Functional Connectivity Associated with Hypnosis. Cerebral Cortex, cercor;bhw220v1. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw220 ↩︎

-

Alexander, J. E., Stimpson, K. H., Kittle, J., & Spiegel, D. (2021). The Hypnotic Induction Profile (HIP) in Clinical Practice and Research. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 69(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2021.1836646 ↩︎

-

DeSantis, A. S., Dubowitz, T., Ghosh-Dastidar, B., Hunter, G. P., Buman, M., Buysse, D. J., Hale, L., & Troxel, W. M. (2019). A preliminary study of a composite sleep health score: Associations with psychological distress, body mass index, and physical functioning in a low-income African American community. Sleep Health, 5(5), 514–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2019.05.001 ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.