POSTS

Happiness in the lab, part 3: Engagement

by Luis P. Prieto, - 12 minutes read - 2409 wordsHave you ever found yourself avoiding your supervisor, or the thesis meetings, or just not wanting to open the manuscript file you have to finish? Then you might have some problems engaging with your research work. In this third post of the series on finding more happiness in your research, I look at how engagement at work is defined, how to assess your own levels of engagement, and some research-backed practices to help you engage better with your work and find your “flow”.

We have all been there: not wanting to get up in the morning, dreading to open a difficult text we’re writing, avoiding our advisor or colleagues because they will bring up the project we don’t want to work on… Unfortunately, this does not go away once you finish the dissertation. One of my moments of lowest engagement was one or two years ago, already a senior researcher, when I realized that I had been overworking long hours for the last few years, but had very little to show for it. Not only then I started dropping balls left and right, saying no to things to keep my work hours reasonable – I stopped exerting myself altogether. A strange layer cynicism coated my work hours, replacing the drive to do the best that I could. I stopped doing activities I had always cherished, like thinking up a new research study, or reading the latest papers on my field. What was going on?

E is for Engagement

You probably guessed it by now. After purpose, the second pillar of happiness at work (spelling out the acronym P.E.R.K.) is engagement. In the Berkeley course “The Foundations of Happiness at Work”, Keltner and colleagues define engagement as “applying ourselves in a sincere and dedicated way that leaves us feeling fulfilled by our work”. Again, a bit of a squishy concept, but probably you can intuit clearly when you feel (or not) like this during your working hours.

There seem to be several aspects to engagement at work:

- Attention. The first half of the definition above revolves around our attention as we work, and whether we are able to focus on what we are doing fully, or rather our mind wanders elsewhere. Interestingly, such mind-wandering seems to be associated with lower happiness at work1. In the opposite extreme are the experiences of “flow”2, when we get so engrossed in doing the task at hand that we lose track of time.

- Emotion. The other side of the definition above has to do with how we feel when we work. More concretely, it is about prioritizing positive emotions while we work, like curiosity, gratitude, enthusiasm, or amusement. And conversely, avoiding negative emotions like regret, shame, hate or conflict. It makes all the sense: why would we engage in a task that often causes us pain and suffering? Instinctively, we would try to avoid such situations. On top of that, it seems that positive emotions “broaden our thought-action repertoires”3. That is, our mind is able to consider many different courses of action or patterns of thought, vs. the urge to act in a single particular way like the fight or flight instincts (when we think we are in danger). This broader repertoire in turn can help us create better social connections or find creative solutions to the problems we face at work (which probably sets us up for more positive experiences at work in the future).

- Progress. A third element that is mentioned when talking about engagement at work, is to have a sense of daily progress towards your goals. This might be about feeling achievement for what we do (again, a positive emotion), but it might deserve separate attention, since some studies suggest that progress is the single most important factor that predicts the engagement of people with their work4. We also mentioned this “sense of progress” as one of the main factors appearing on research about Ph.D. dropouts and persistence (i.e., which doctoral candidates persist in engaging with their research work until completion).

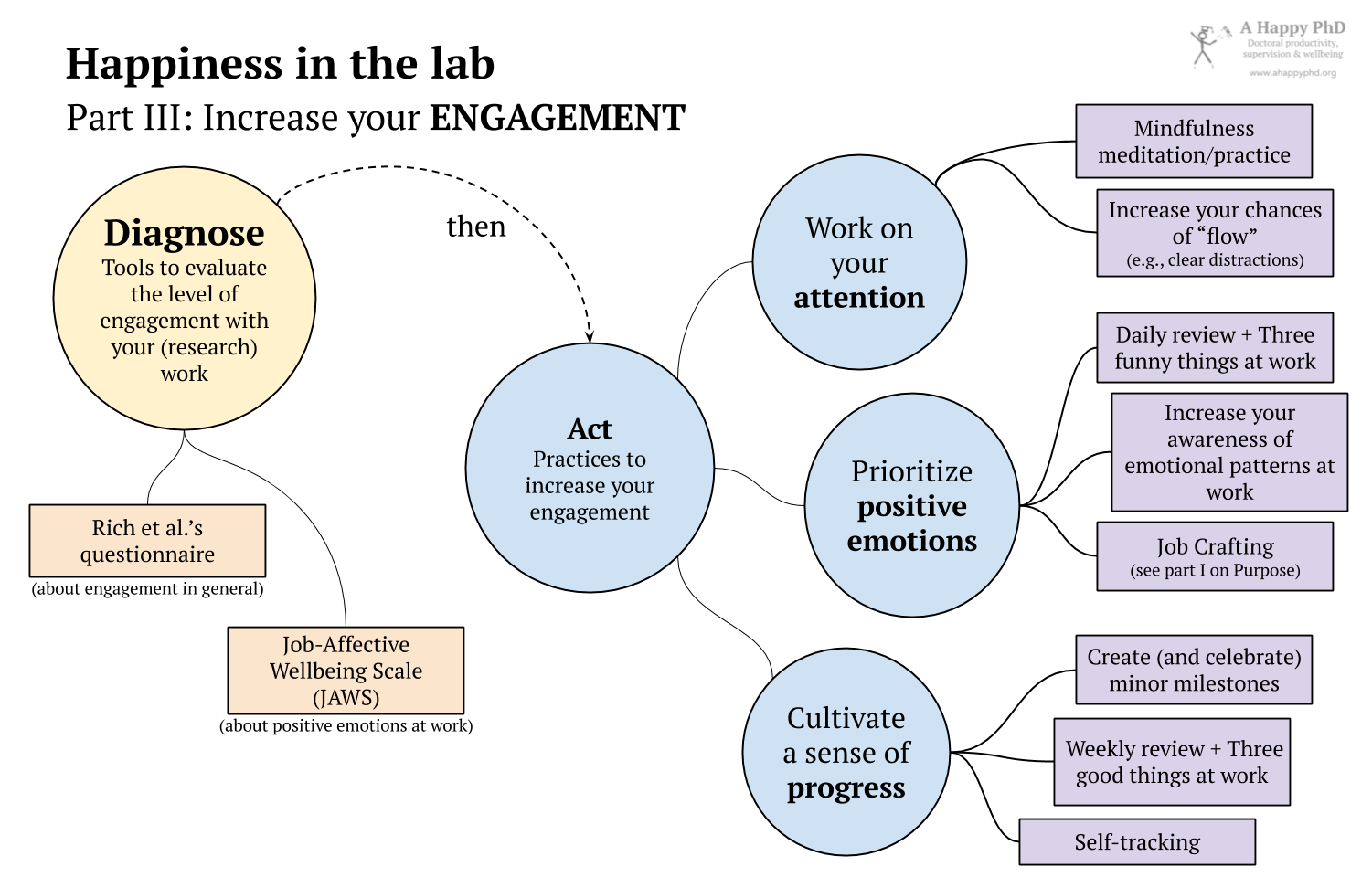

Diagnose: How engaged are you with your research work?

Now that we know what we mean by “engagement”, I suggest you take a few minutes to test yourself and assess how engaged you are with your research work, using the following instruments:

- Try this questionnaire about engagement at work, based upon Rich et al.’s research on job performance5. This brief set of questions should give you an overall idea of how engaged you are with your daily research work.

- Since positive emotions play such an important role in our engagement with work activities, you may also want to do this Job-related Affective Well-being Scale (JAWS), based on the work by Van Katwyk and colleagues6, to see what kind of positive (or negative) emotions appear more often at your workplace.

Do not despair if you don’t score very high in these – but do not ignore it either. I was quite disengaged myself at several points in my career, but there’s a few things you can do to progressively engage better with your research work.

Act: strategies and practices for better engaging with your research

It seems kind of counter-intuitive that you can actively do something to feel more engagement about an activity. You either feel it or not, right? Yet, since we know a few of these key components of engagement (attention, positive emotions, progress), we can make engagement more likely to happen, by trying a few simple practices:

- If you think that mind-wandering and lack of focus are the weakest link in your chain of engagement elements, you can choose to work on your attention. Try these out:

- One way to avoid mind wandering, at work and elsewhere, is to cultivate your ability to pay attention. A common way to do this, coming from the Buddhist tradition, is to try out mindfulness meditation. The research on applying such techniques with Ph.D. students is still in its infancy (probably I will cover that in a later post), but there is some evidence that mindfulness training can help with anxiety of doctoral students7. There are simple exercises that you can try if you have never done this, like a “raisin meditation”, mindful breathing or body scan exercises. However, it is quite likely that the effects will be relatively small at first, since this is a skill that takes time to develop. Given the constant pull of our environment towards distraction (did anyone say ‘smartphone’?), don’t expect quick fixes!

- If, on the other hand, you want to increase your chances of getting to these (usually enjoyable) “flow” experiences where you get lost in what you’re doing, you may have to modify a bit your research work habits and environment. This post by Leo Babauta gives several tips and tricks to increase your chances of that: carving out quiet time when you feel at your peak, finding a task that is challenging, and that you feel is important and meaningful for you (see the last post about purpose), clearing away distractions, … many of these we already mentioned when talking about the “pomodoro technique”, but here you also want to practice having this kind of focused attention for progressively longer spans of time.

- Following up the elements of engagement, another common piece of advice to increase engagement is to prioritize positive emotions at work. Of course, who does not want more good vibes in the lab? The problem is how: some situations, some people are just shitty and make you feel bad! Well, you can try this:

- In the Berkeley course the instructors suggest to try a simple exercise called “three funny things at work”, which basically asks you to take ten minutes at the end of your workday, every day for a week, to write down the three funniest things that you encountered that day, and why you found it funny. That simple! There is research that shows that this can increase your happiness even six months after having done it for only one week8.

- Another simple way to look at this issue is just to increase your awareness of patterns and situations in your research work that have some kind of emotional impact. You can take some time to look at the JAWS questionnaire above, and go over each of the emotions mentioned there, writing down when was the last time you experienced each of those emotions in your research work. Very concretely, write down: who was there? what were you doing? where were you? If you then take a look at all the ones that are positive, you may see patterns, people or places that emerge. You may then try to work more in such situations (to the extent that you are free to do so). And the same thing would go for avoiding the patterns and situations that often appear in your negative emotion episodes.

- A more systematic way of doing a similar thing would be to engage in job crafting: tweaking systematically not only what you do or who you interact with in your research; also changing how you think, how you frame what you do in the lab. Since this practice we also mentioned last week when talking about finding more purpose, I will try to not repeat myself and encourage you to go to last week’s post where you can find practices and training materials explaining job crafting in more detail.

- You probably guessed by now, the third area of practices to improve engagement has to do with cultivating your sense of progress at work. This is actually a hard nut to crack in the case of Ph.D. students (and researchers in general), since we have many long-duration tasks and projects, e.g., we tend to think of the dissertation (or any research project) as a big, binary task/project (which you have either finished or not), which leads to progress only being perceived once every few years!

- Teresa Amabile (who came up with this idea of the “progress principle” or “the power of small wins”, as key to employee engagement)4 provides certain general tips for knowledge workers, like creating more minor milestones in your work, so that you perceive progress more often. For example, you can try to put in your to-do list sections of the paper you have to write (or even paragraphs!). It is also important to celebrate your progress in these milestones (otherwise, the feeling of achievement will be drown out by the urge to get immediately back to work and finish the next thing).

- Another simple technique to increase your sense of progress is to do a weekly review of what has happened at work at the end of each week, and journal about three good things that happened there (meaning, you made progress on something you value). Personally, I have found weekly (and daily, and quarterly) reviews quite important in my own productivity and sense of progress, so probably I’ll do a separate post on that in the future.

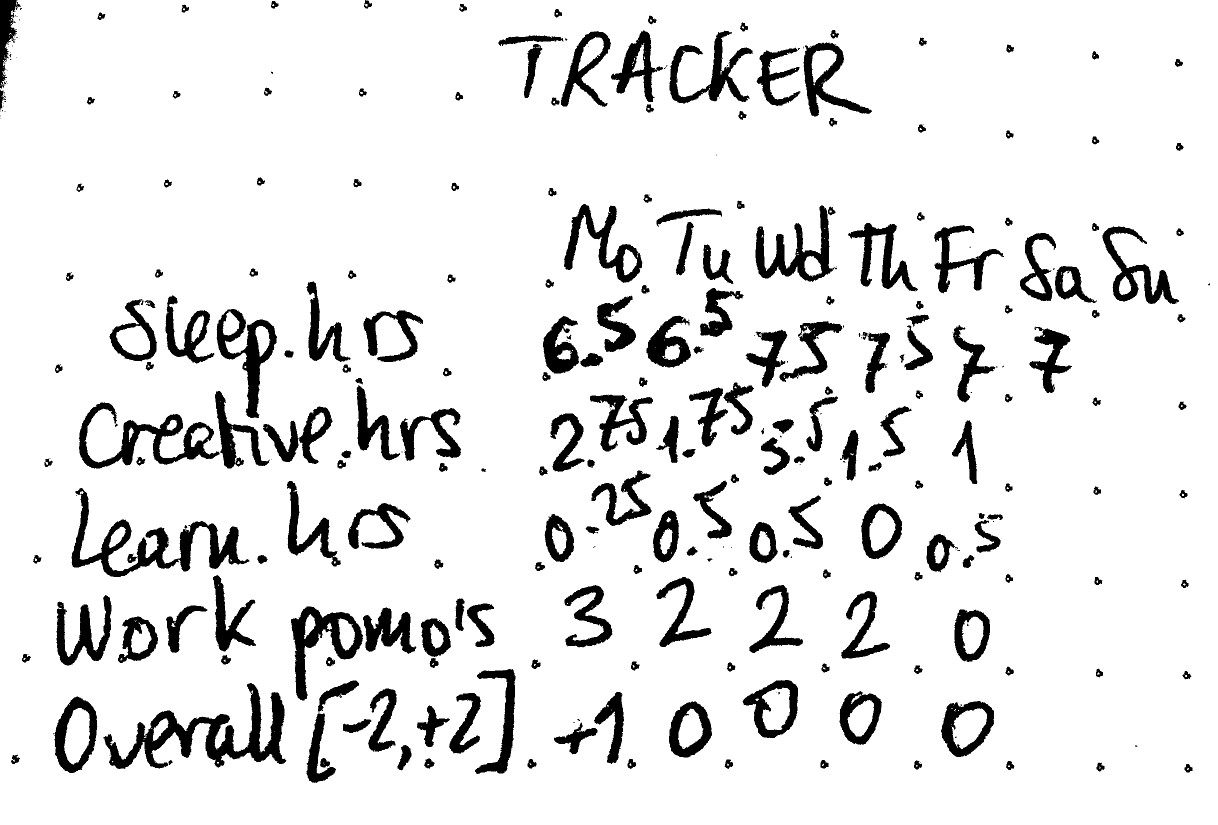

- Another practice that I have experimented a lot with lately, which is related to getting a more frequent sense of progress, is the habit of self-tracking: basically, noting down somewhere (on paper, or on a spreadsheet) some quantitative or qualitative data about your progress, every day. Just like people track steps in their fitness trackers, but for your research work stuff. I have found it quite interesting to understand myself and my patterns of work and happiness, but then again, I am weird ;) As a Ph.D. student or researcher, the actual hard thing is to find what to track: what is it that you do frequently enough to be a useful marker of progress, but at the same time is meaningful enough to give you the sense that you progressed in something important? I’m actually thinking to start researching this topic actively (more news to come soon about this)…

That was it for engagement. In case you are more of a graphically-minded person (I know I am), you can also use the graph below to remind yourself about the tools for diagnosis and practices for increased engagement that I have mentioned in this post:

Since that time when my engagement with research reached an all-time low, things have gotten better. I’ve started (or re-started) doing many of the things I mention above: I started being systematic in blocking uninterrupted slots of time for focused work, I started prioritizing those research activities that I had found brought me most joy (like writing, data analysis or running workshops), I track my small daily achievements, and I periodically review and reflect on them, I practice mindfulness more regularly… Still, my engagement is by no means superlative, but throughout those periodic reviews, I can see the slow but steady improvement.

What about you? Do you feel engaged with your research work, or do you surprise yourself avoiding (parts of) it? Have you tried any of the practices above? Do you have any tips and tricks to keep yourself motivated and engaged? Let me know in the comments below!

-

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932–932. PDF here. ↩︎

-

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The concept of flow. In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 239–263). Retrieved from here. ↩︎

-

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. ↩︎

-

Amabile, T. M., & Kramer, S. J. (2011). The power of small wins. Harvard Business Review, 89(5), 70–80. Retrieved from here. ↩︎

-

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/10.5465/AMJ.2010.51468988. ↩︎

-

Van Katwyk, P. T., Fox, S., Spector, P. E., & Kelloway, E. K. (2000). Using the Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.219. ↩︎

-

Barry, K. M., Woods, M., Martin, A., Stirling, C., & Warnecke, E. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on doctoral candidate psychological status. Journal of American College Health, 67(4), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1515760 ↩︎

-

Wellenzohn, S., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2016). Humor-based online positive psychology interventions: A randomized placebo-controlled long-term trial. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(6), 584–594. PDF here. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.