POSTS

Happiness in the lab, part 4: Resilience

by Luis P. Prieto, - 14 minutes read - 2884 wordsNo matter how meaningful your research feels to you, no matter how engaged you are when doing it, sometimes things just don’t work out as you expected. Papers get rejected, proposals are not funded, data gets mangled and needs to be collected again… plus all the non-research-related stumbling blocks that life throws at us, from sickness to accidents or family tragedies. How fast and how well can we recover from those setbacks that throw us off balance? This fourth post in the series goes over the concept of resilience as an important pillar for staying happy and fulfilled while working in research. Read below for instruments you can use to gauge it, and practices to help you stay resilient in the face of difficulties.

Do I remember the last time something went wrong unexpectedly and overturned my research work? Boy, I can remember ten without even trying hard. That literature review that we had spent months developing and that got rejected by reviewers on grounds that I did not understand (and in a conference, not even a journal!). Or that research funding proposal that our whole team had spent months polishing to perfection, and didn’t even make it past the first cut.

The academic research world is setup like this: a limited amount of positions, publication venues or funding for projects – and a fast-growing number of PhD students and research teams, especially in developing countries. As a consequence, such setbacks are becoming more and more common, both for Ph.D. students and any other researcher (ask anyone who usually applies for funding to the European Union). Our next pillar for happiness in your research work has a lot to do with this kind of episodes, and how to survive them…

R is for Resilience

So, what is resilience? In UC Berkeley’s online course about the topic (“Mindfulness and Resilience to Stress at Work”), the American Psychological Association’s definition is given: “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or even significant sources of stress”1.

Many of us may think of resilience as a personal trait (either you have it, or you don’t). We all know somebody that is just able to bounce back, no matter what life throws at them. And it is true that multiple such factors affect resilience: from genetics, to education, early life (or later) traumas, your available economic resources… all those affect your ability to recover from setbacks. However, psychologists also think about it as a process (i.e., something you can practice), and an outcome of those resilient processes. This includes daily thought and behavior patterns, habits, social situations… choices we make, which we can change. For instance, having an encouraging attitude towards ourselves, focusing on solving the problems rather than on how bad the problems are, or cultivating social connections that empower us.

It is also important to note that resilience is not only about facing the big crises that appear in our lives and our research, but also the smaller stuff that happens every day, “handling the stresses of work with grace and equanimity […] and ease”, as Keltner puts it in the online course “The Foundations of Happiness at Work”.

Lately, you may have heard also the term “grit” being used in a similar fashion (popularized by Angela Duckworth’s TED talk and book2). Grit is about long-term perseverance and passion for long-term goals (which seems exactly what we need to do a Ph.D.). While it is not very clear how to become “grittier”, Duckworth herself mentions ideas like developing a growth mindset3: basically, the belief that your intellectual abilities are not fixed, and can be developed (and its corollary: we can get better at solving our problems, so they are not permanent, and can be overcome). Again, we see that developing certain patterns of thought can be useful to be resilient and persevere.

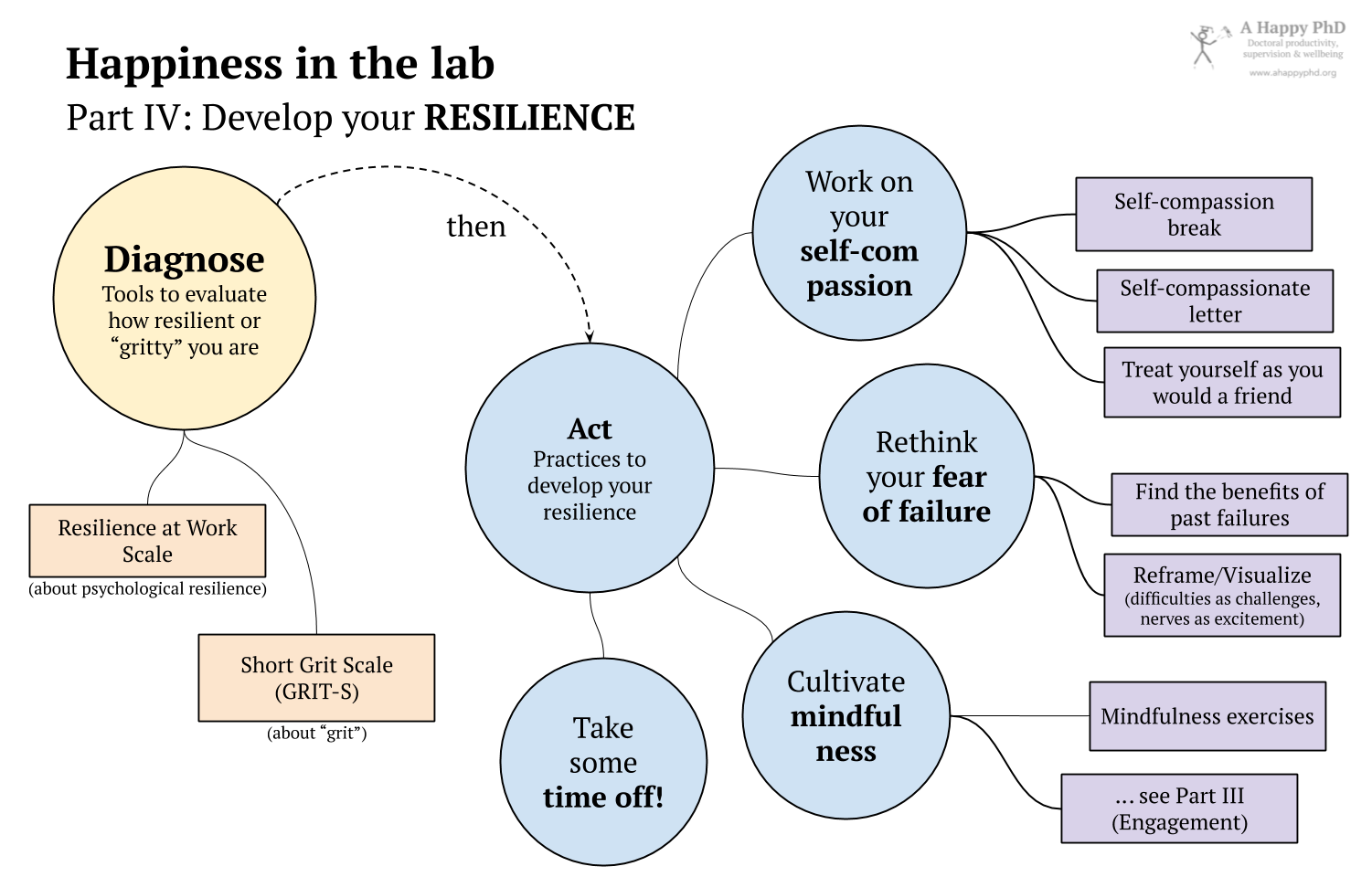

Diagnose your resilience

After the post on purpose, and the one on engagement, I guess by now you know the drill: How do we know whether resilience is one of our strong suits, or it is something we want to work on more intensely? You can try these two short questionnaires to get an initial idea:

- Try out the Resilience at Work Scale, based on the work by Winwood and colleagues4.

- If you are curious about whether you are a gritty person, you can try the Short Grit Scale (GRIT-S), developed by Duckworth & Quinn5.

One important caveat needs to be made, though: as you may notice, these diagnostic tools are self-report scales (i.e., they ask about what you think of yourself). While this is a reasonable (and easy to gather) measure, it may not measure perfectly how we act when misfortune actually hits us in real life. This is also an important limitation of much of the research on how to train resilience (see below): the effectiveness of the practices and programs is normally measured by such self-report instruments, not by checking how well people recover from actual bad stuff in their lives afterwards.

Act: Practices for greater resilience in research work

How do you become more resilient? is there a “magic pill” for grit? From my reading of research and resources on the topic, it seems that resilience and grit are a bit more difficult and slow to develop. This makes sense, since resilience and grit are a complex combination of knowledge, attitudes, habits, choices… many of which are very contextual (we may learn to act resiliently in the training room, but forget all about it when we are in the hospital waiting for the doctor to tell us about our grandma’s injury).

It seems that there are two main approaches to developing resilience: programs based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and others based on mindfulness training. From a review of randomised controlled trials of such programs6, it seems that those based on mindfulness7 or those that mix both approaches8, tend to have bigger effects, on average. Moreover, these effects stay even months after the program itself ended!

If we look at programs and practices for resilience in doctoral students, the research is still in its infancy. We already mentioned last week the use of an 8-week mindfulness program9, which not only seems to improve student anxiety, but also resilience and other aspects of what they call “psychological capital”. The Arizona State University also has a program called CareerWISE for women researchers in STEM fields, which reports a strong effect on doctoral candidates’ resilience and overall persistence in the PhD10. However, this is a very comprehensive program with communication skills development, problem solving skills, and many other trainings besides those directly aimed at resilience (their assumption being that working on multiple fronts will help address the many potential causes of women dropping out of STEM PhDs). It makes sense, if you ask me.

As we see, resilience training that works seems to require quite a serious effort and specialized training. Yet, is there anything you can try where you are, without going so deep? In the UC Berkeley courses I mentioned above, several easier practices are mentioned:

- One kind of practice that I have seen both in the advice about resilience and grit, is to work on your self-compassion, on a more “optimistic self-talk”. Self-talk refers to this kind of “internal monologue” that we often have with ourselves, and which can be harsh especially when bad things happen (“I’m such a loser”, “I’m so bad at X”, “this thing I produced is still so wrong”, etc.). These patterns of thought are internalized during years and years from infancy, and it has been shown that, rather than driving us to success and perfection, they lead more often to low self-esteem, negative perfectionism, procrastination, and rumination. However, such mental patterns can be slowly changed, by re-conditioning ourselves to be more self-compassionate: being mindfully aware of the current struggles we are facing, being kind to ourselves and recognizing them as part of our common humanity… in short, “treating ourselves as we would a good friend”. Self-compassion has been linked to better wellbeing, lower stress, anxiety, depression and perfectionism11.

- An entry-level practice you can try is to take a “self-compassion break”: you take a 5-minute break to fully feel a stressful or difficult situation, its effects on you, and then recognizing that such situations are an integral part of life, and wishing well to yourself.

- Other research-backed practices12 you can try are the self-compassionate letter, or treating yourself like you would a friend. These practices can feel a bit weird at first (e.g., stopping in your lab for 5 minutes with your eyes closed – tip: you can also try doing it the bathroom, for improved intimacy). Yet, you will probably feel some beneficial effects immediately (let’s face it, anything feels better than the full force of our shame and self-deprecating thoughts when something goes awry).

- Another interesting mental pattern that you can work on, is to rethink your fear of failure. Before we try something difficult or uncertain, we are often terrified of failure, and try to avoid it at all costs (including just giving up even before starting). However, failures very often are not as bad as we think: indeed, in retrospect we think they are valuable learning experiences! To help you change this unhelpful thought pattern, try these exercises:

- Find the benefits of past failures. Pick a past failure. Write down three things you learned from it. Then reflect: have you made any changes to prevent future failures like this? Then, you can take the time now to make some of those changes. You can try variants of this exercise by asking your labmates or advisors about failures of theirs, and what they learned from them.

- Reframing and visualization. If you have an important, difficult task at hand, try to reframe it as a challenge, not as a threat. Take some time to remind yourself and write down about previous similar challenges that you overcame. Visualize yourself having success at the current challenge (vs. ruminating about what could go wrong). If you feel nervousness, shakiness, tell yourself that you are excited about doing the task, that this energy, this “good stress” is your body helping you to rise to the challenge (as per Kelly McGonigal’s classic TED talk).

- Aside from the practices above to change your mental habits, mindfulness practice is probably the most-often cited kind of practice to improve resilience (and many other wellbeing variables13), often in the form of long programs (like the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, MBSR). While you can do such full-length programs (like this free online one), I also reviewed a few simple practices to cultivate mindfulness in my previous post on practices to cultivate engagement. Or you can try a short guided meditation like this one. Give them a go!

- Finally, one often-overlooked practice that helps boost resilience: take some time off! It is very hard to change your mind habits, be mindful, endure setbacks or stressful situations, when you don’t have the mental (or physical) energy. You should be taking time off at multiple levels: some time daily to do something unrelated to your research (be it sports, a creative hobby, or just enjoying time with family and friends); some days every week where you leave your worries behind (the concept of “weekend”, remember?); and every year, take some holidays. Like, real holidays. We can argue about what is the ideal length (some research suggests 7-10 day stretches work well14,15), but what seems to be certain is that if you don’t take holidays, you are more likely to burnout, or just die earlier16.

One important thing to point out about these practices for resilience, is that they often are quite dependent on individual differences6: some may work great for some people, others not so much. This means there is only one way to know what will work out for you: try them out, and track the results (either formally with diagnostic tools like the ones above, or just more free-form journaling of how you feel over time). More posts on this idea coming soon!

Bounce back… but be careful!

Just before wrapping up, a word of warning: sometimes all this talk about resilience and developing it can act as a sort of “band-aid approach” to curing a serious internal wound. We address the superficial symptoms (e.g., our feeling stressed) without addressing the deeper root causes (e.g., the work culture in my lab is toxic). This danger is common to much of the positive psychology advice and practice out there (which I sometimes draw from), so I will probably talk more about this issue in a later post. So, just to be clear, resilience is not about:

- … accepting or acquiescing to unreasonable demands, bullying, coercion, exploitation, unfairness, or other people being adversarial, as you do your research work. Sometimes situations or people around you need to change (or you may need to get away from them).

- … complacence or helplessness about situations we do have control about. If you think there are things in your hand to change the difficult situation or the adverse outcomes you are facing, act to change the situation, don’t just try “jedi mind tricks” like the ones above. If your experiment failed because you are lacking a certain skill, then get some training, or expert help – don’t just work on your mindfulness chops!

Personally, I am still trying to rebound from the latest funding proposal that got rejected around July: I have taken a real summer break, convinced myself that such episodes are an integral part of a researcher’s life, identified things that I can change to do better next time. As I start with some new projects and research ideas (including some new things to try out in this blog), there is some fear of failure, sure. But maybe it’s just excitement for doing work that I think is important and meaningful. And, for some reason, life doesn’t feel so bleak right now, even as the cold Nordic autumn creeps in.

What about you? do you have tips or tricks to help you bounce back from a rejected paper or bad experiment? Let me know in the comments below!

-

American Psychological Association (2014). The Road to Resilience. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Online at: https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience ↩︎

-

Duckworth, A., & Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance (Vol. 234). Scribner New York, NY. ↩︎

-

Based on the research by Carol Dweck and others, e.g., Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(31), 8664–8668. ↩︎

-

Winwood, P. C., Colon, R., & McEwen, K. (2013). A practical measure of workplace resilience: Developing the Resilience at Work scale. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(10), 1205-1212. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182a2a60a ↩︎

-

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. ↩︎

-

Joyce, S., Shand, F., Tighe, J., Laurent, S. J., Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, S. B. (2018). Road to resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open, 8(6), e017858. ↩︎

-

E.g., Aikens, K. A., Astin, J., Pelletier, K. R., Levanovich, K., Baase, C. M., Park, Y. Y., & Bodnar, C. M. (2014). Mindfulness goes to work: Impact of an online workplace intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(7), 721–731. ↩︎

-

See, for example, Cerezo, M. V., Ortiz-Tallo, M., Cardenal, V., & de la Torre-Luque, A. (2014). Positive psychology group intervention for breast cancer patients: A randomised trial. Psychological Reports, 115(1), 44–64. ↩︎

-

Barry, K. M., Woods, M., Martin, A., Stirling, C., & Warnecke, E. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on doctoral candidate psychological status. Journal of American College Health, 67(4), 299–307. ↩︎

-

Bekki, J. M., Smith, M. L., Bernstein, B., & Harrison, C. (2013). Effects of an online personal resilience training program for women in STEM doctoral programs. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 19(1). ↩︎

-

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004 ↩︎

-

Again, the positive effects of these small practices have been documented on longer programs, e.g., the eight-week self-compassion program in Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923 ↩︎

-

Hyland, P. K., Lee, R. A., & Mills, M. J. (2015). Mindfulness at Work: A New Approach to Improving Individual and Organizational Performance. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(4), 576–602. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.41 ↩︎

-

Etzion, D. (2003). Annual vacation: Duration of relief from job stressors and burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 16(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2003.10382974 ↩︎

-

de Bloom, J., Geurts, S. A. E., & Kompier, M. A. J. (2013). Vacation (after-) effects on employee health and well-being, and the role of vacation activities, experiences and sleep. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 613–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9345-3 ↩︎

-

Gump, B. B., & Matthews, K. A. (2000). Are Vacations Good for Your Health? The 9-Year Mortality Experience After the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(5), 608. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.