POSTS

Addiction and the PhD (book extract)

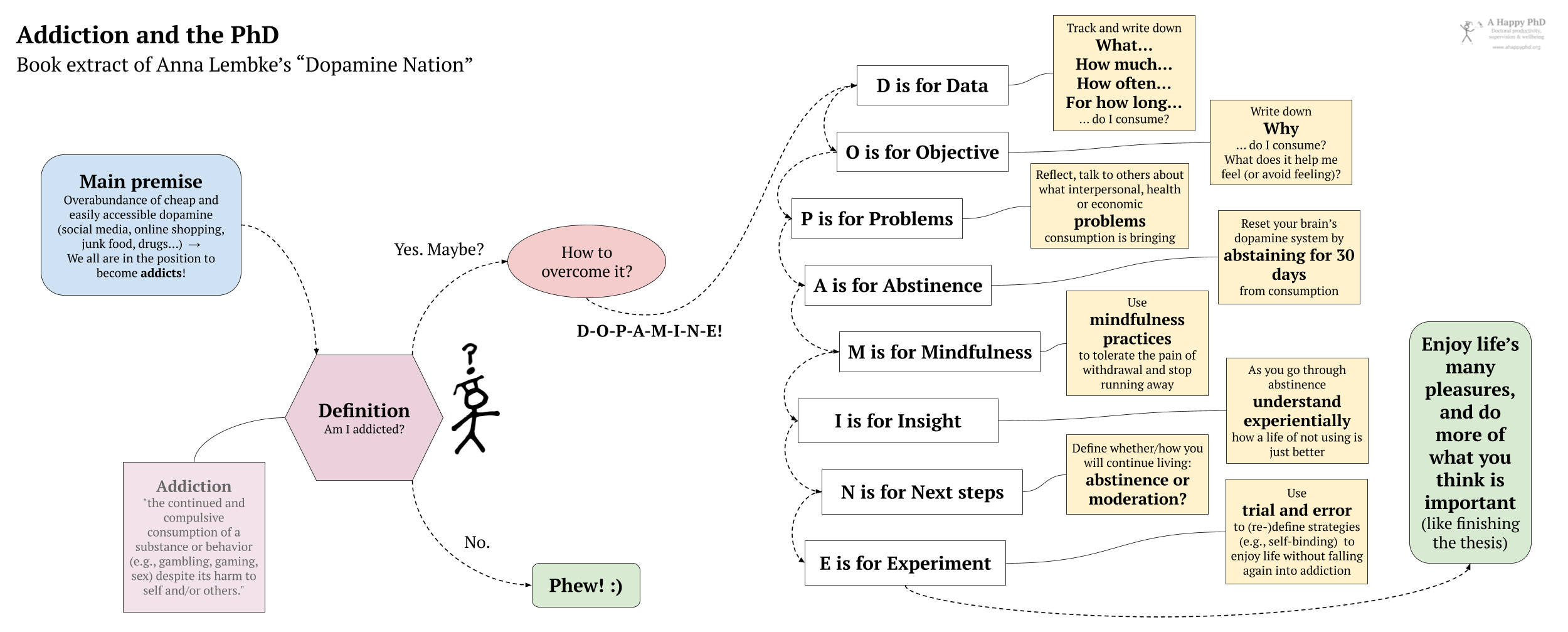

by Luis P. Prieto, - 12 minutes read - 2430 wordsSocial media, porn, eating sugary things, shopping, alcohol, or spending our days anxiously reading the news… Most of us have behaviors or substances we do compulsively, to the point that it damages our relationships and our ability to achieve important goals (including, of course, finishing our PhD thesis). Dopamine is at the heart of these addictions. In this post, I distill lessons learned from reading Anna Lembke’s book “Dopamine Nation”1 about how dopamine works, how to face our addictions, and do more of what we think is important.

I came across this book at an interview with Lembke in the Huberman Lab podcast, and found it surprisingly interesting and applicable to my own life. We tend to think that addiction is an affliction of other kinds of people. Yet, I found many of the book’s ideas almost universally relevant

In this new kind of post (the book extract), I’ll try to do not just a book summary, but rather a distillation of some of the book’s insights, re-contextualized for application to the PhD (and research in general).

Dopamine?

Let’s start with the basics: what is dopamine? In simple terms, it is a chemical that our brains produce, a neurotransmitter. More concretely, dopamine is related to motivation, desire and learning behaviors. Dopamine had a very important role for the survival of animals in general, and for our evolutionary ancestors in particular. Let’s imagine I’m a hunter-gatherer in the African savannah. If I find some edible plant in a particular spot, and I eat it and find it’s nice and sweet, levels of dopamine will increase to help me create and reinforce neural connections and learn, not only where I found it, but also what I did to peel the plant, and every other behavior involved in getting the pleasurable stimulus. It will also motivate me to come here tomorrow, and repeat the same behaviors. Very useful if you are in an environment in which food, water, etc. are scarce.

Dopamine is not only involved in processes related to food, but also sex, social relations, entertainment (including, of course, recreational drugs like alcohol and cocaine)… basically anything we find pleasurable and we feel motivated to get more of. Indeed, dopamine has been called “the molecule of more”2. Also, it is important to know that different kinds of pleasures activate dopamine to different degrees: eating chocolate will increase levels of dopamine by about +55%, sex by +100%… and amphetamines by +1000%! This does not mean you feel 10x more pleasure from the latter over the former. Dopamine is about the desire, the motivational pull to do something, rather than how good the original stimulus felt in the moment.

Why you should care about dopamine during your PhD

Yet, most of us are not gathering plants in the savannah anymore. We are doing research, getting our PhDs… why is knowing about dopamine important for us? Because we live in an environment that is very different from the one in which our dopamine mechanisms evolved. Lembke’s main point in the book is that, given the current overabundance of cheap and easily accessible dopaminergic stimuli (drugs, salty/sugary food, social media, online shopping, porn, ebooks…), if we are not already addicts today, we all will be very soon in the position to be addicts.

One would think that being surrounded by easily-accessible pleasurable things would be a good thing (for many, that’s the definition of heaven). Yet, high doses of dopamine in our brain can hook us on behaviors or substances not in our best interests, and sets our brains up to be unhappy!

How does this problem develop? One key fact uncovered by brain research is that the pleasure-pain system in our brain always tries to come back to equilibrium (sometimes called “homeostasis”). After the initial pleasurable stimulus, our brains generate a pain, slightly stronger than the pleasure was (which we experience as craving for more of the pleasurable thing). This ensured that our ancestors did not remain forever in the bliss from eating the first nice food they found, but rather continued striving for more (or sex, etc.). Again, good for survival in environments where these things are scarce.

Lembke offers the metaphor of the brain’s pleasure-pain system as a balance (like the ones we can find in playgrounds), with pleasure on one side and pain on the other. When we get a pleasurable stimulus (say, our snarky Facebook post received a lot of likes), the balance tips towards the “pleasure side” (a little if the pleasure is small, and a lot for very addictive drugs). In order for the brain to achieve homeostasis, a bunch of gremlins (a few if the tilt towards pleasure was small, and many of them if the stimulus was stronger) hop over the “pain side” until it tilts slightly to the pain side. This is the moment when we forget about the pleasure we got from the stimulus, and crave more of it (what else can we write snarkily about?). The problem is, after several such cycles of pleasure-craving, the behavior becomes compulsive. And the gremlins don’t even bother to hop off the balance, and we need bigger and bigger doses of the pleasurable stimuli just to “not feel bad”. We are now addicted to the behavior/substance!

Lembke defines addiction broadly as “the continued and compulsive consumption of a substance or behavior (e.g., gambling, gaming, sex) despite its harm to self and/or others.” If I stop and think about how many important things (big and small) I have foregone just to have a little more of the pleasurable things I wanted at the moment… I realize I have been addicted my whole life! Just considering the period while I was doing the doctorate, I can count many addictions: computer games, spicy junk food, porn, podcasts, monitoring and comparing Google Scholar citations, reading self-help books, reading fantasy/scifi books, … Of course, doing any of these occasionally is perfectly fine, and I’m very fortunate none of these stimuli has the strength of metamphetamines. They did not completely break my life. But, where would I be if I had not done all those things in excess, for long periods of time? Probably in a better place.

Dealing with addiction in the PhD

Lembke not only lays out the widespread problem of addiction in the modern world. She also shares eight things one can do to face the challenges of addiction, in rough chronological order. You can remember them by the acronym D-O-P-A-M-I-N-E:

-

Data: Once we notice there is a behavior or substance we may be addicted to (hint: this often comes with certain sense of unease, an inability to enjoy other sources of pleasure we used to like), we start by gathering the facts of our consumption. What substances or behaviors do we do in excess? How much, how often and for how long do we do/have them? Keeping a written record of this for some time, will help us understand our baseline (similar to the journaling and self-tracking practices I mentioned to understand progress in the dissertation).

-

Objectives: Then, we can reflect and notice what the substance/behavior helps us achieve (i.e., why do we do/take it?). We should go beyond “I like it”, into what is our personal logic for using. For instance, we can look at the data from the previous step, and try to find triggers and patterns (e.g., “I turn to X when I sit down to write my papers, because I think my writing is awful and the paper will not be accepted”). Very often, we turn to addiction because we are trying to avoid difficult situations, feelings or thoughts.

-

Problems: We can then reflect and discuss with people around us what are the downsides of the addiction. Is the use creating health problems? economic problems? interpersonal conflict? This step is often difficult to see for the addict him-/herself (because we are imbued in our “personal logic” from the point above). Thus, the need to talk to others who know you well about it (e.g., “Hey, do you think I do too much X? what impact would you say it’s having on me/on our relationship?").

-

Abstinence: Armed with this understanding of our addiction, we then need to restore our brain’s dopamine homeostasis (i.e., to stop the craving cycles and recover the capacity to feel pleasure naturally from other sources). According to Lembke, the most effective way to do this is through complete abstinence from the stimulus we’re addicted to. In her experience, normally it takes about one month of abstaining for the dopamine system to come back to normal. By then, the effects of abstinence on our life should be palpable: we will be able to enjoy other things again, and we may start to feel generally better, without the continuous craving/pleasure cycles of the addictive substance/behavior.

- Warning! Some substances come with life-threatening withdrawal symptoms (like heroin and other hard drugs). In those cases, the abstinence process should be monitored/adjusted with the help of professionals!

- Warning! Do not deal with the abstinence by engaging in other highly dopaminergic substance/behavior (e.g., stopping the compulsive shopping by taking up alcohol instead). This can lead to cross-addictions!

-

Mindfulness: During the abstinence period, the pain (i.e., the craving) will get worse. To help us to tolerate the pain of withdrawal we can turn to mindfulness (“the ability to observe what our brain is doing while it’s doing it, without judgment”). Especially if our addiction is tangled with the difficult sensations that doing a PhD sometimes brings, mindfulness exercises like the ones I mentioned here or here may help us stop running away from the painful thoughts/emotions that trigger our addiction (and the craving itself).

-

Insight: As abstinence goes on, we will start to get clarity into the problems addiction was causing, and how our personal logic for using may be misguided. For instance, our computer games consumption when paper writing gets hard does not really make the problem go away (rather, prolongs it endlessly as the writing process drags on). We will understand how a life of not using is better. Yes, it has some uneasy moments, but we can mindfully see how those feelings pass over us like a wave (if we choose to stop and notice them without going to our addiction). And we can continue doing what we think is important (like finishing that first draft of our paper, which is critical for us to get our doctorate and develop the research skills we want).

-

Next steps: After one month of abstinence from the stimulus, we can decide what we want to do going forward, from a place of equilibrium in our brain’s dopamine system. Do we want to continue abstaining, or do we want to use the behavior/substance in moderation? This moment is quite tricky, as we can quickly relapse into the addiction. Moderation can work with less severe forms of addiction, but for more addictive substances or behaviors, abstaining may be the only way to go forward without falling back into addiction.

-

Experiment: Over time, through trial and error, we can find out what is the level of use (if any) that works for us, to maintain a healthy pleasure-pain balance. Especially important at this stage are different self-binding strategies (i.e., rules and boundaries we set for ourselves to help us control our consumption, or abstain entirely). For instance, we can define for ourselves that we will only play the computer game we’re addicted to for one hour a week on Friday, we can put a very complex password on our account, and give the password to our partner (so that we have to ask them every time we want to play). These strategies are especially important for addiction to things that are ubiquitous, difficult or impossible to eliminate completely, like food or smartphones.

The way I phrased the steps above suggests that they can be taken by a person acting alone. However, going through these steps reliably without falling back into our addiction may be easier if we have the help of a professional (e.g., a therapist specialized in our particular addiction, or addictions in general). Further, according to Lembke, there’s about a 20% of people who don’t get better from their addiction-induced symptoms (e.g., depression) by abstinence alone. In these cases, something else may be driving it (like some chemical imbalance in the brain) and may require more specialized (e.g., pharmacological) methods.

Over to you: what is your drug?

The book has many other interesting ideas, such as detailed accounts of self-binding strategies to help us abstain/moderate our consumption (we will see concrete examples of these in the next post), the role of voluntary discomfort (e.g., cold exposure) as a way to enjoy longer-lasting dopamine increases3, or the importance of radical honesty to fight addiction.

But this post has already become quite long. Below you can find a graphical summary of the main ideas in it:

In the next post, I will continue to explore some of these ideas in the context of one concrete addiction that many doctoral students have mentioned to me as being problematic in their lives: the excessive use of social media. For now, stay safe and stay away from your addictions (whatever they may be).

I’ll try to do the same.

According to the definition of addiction above, we may be addicted to anything, as long as we do it compulsively and excessively to the detriment of our goals, our health and the people around us. In Alcoholics Anonymous fashion, the first step is to recognize that we are addicted to something in a way we cannot control. Would you like to share with us (anonymously) what’s your addiction? Please do it in the comments section below!

This post contains Amazon affiliate links, which means that I may get a small commission (at no extra cost to you) if you buy the books I pointed to, using the provided link.

Header image by Andrew Brookes via Westend61. Swing photo from PxHere.

-

Lembke, A. (2021). Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence. Penguin. Buy it at Amazon. ↩︎

-

Lieberman, D. Z., & Long, M. E. (2018). The molecule of more: How a single chemical in your brain drives love, sex, and Creativity–and will determine the fate of the human race. BenBella Books. ↩︎

-

Oddly enough, cold exposure, ultra-marathons and other voluntary discomfort practices can become addictive on their own, so they should be handled with the same care as traditional dopaminergic behaviors/substances! ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.