POSTS

Notes on chronobiology for the PhD (II): The science of breaks

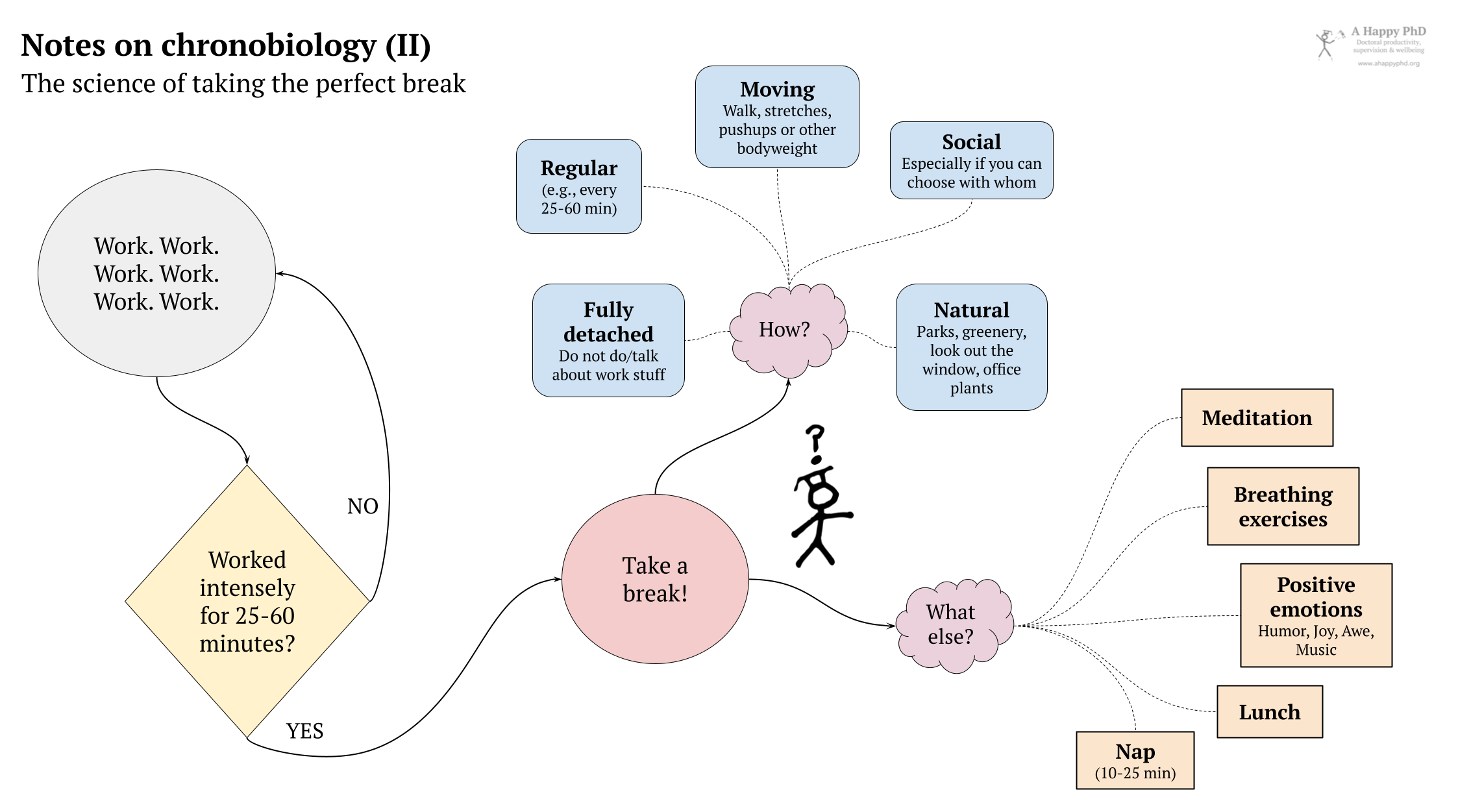

by Luis P. Prieto, - 10 minutes read - 2055 wordsBeing the “cognitive athletes” they are, PhD students (and researchers) should take rest very seriously, to perform at their best. Yet, not all breaks are created equal: timing and other factors affect their effectiveness. Continuing previous dives into chronobiology and taking holidays, this post goes over evidence-based tips and tricks to make your breaks the most restorative and energizing.

In a previous post, we saw that the timing we choose to do certain things (e.g., analytical or creative tasks) has an impact in our performance. As it turns out from research studies, timing also has an impact when we do *no-*things. We already covered tips and studies about longer, multi-day breaks in our post on taking holidays. Below, I go over tips and tricks to make your smaller breaks (within a workday, sometimes also called micro-breaks) more effective and energy-refilling. If you want to know more about this topic, Dan Pink’s book When1 has a great, evidence-based introduction to the subject.

The perfect break

We have all had the experience of taking a 15-minute “email break” when writing a paper, only to find out that, when going back to writing (maybe one hour later!), we are more tired and less motivated than when we took the break. What is going on? How to avoid this kind of un-helpful breaks? In his synthesis of research studies about the science of taking breaks, Dan Pink points out five characteristics that make breaks most effective:

- Regular: Research tasks can be very long (e.g., writing a paper takes hours and hours of dedicated work). There is thus the temptation of not taking breaks until we finish the task at hand. Yet, research shows that our attention spans and energy cannot be on full throttle all the time. It is important to establish some kind of rhythm alternating focused work with small rest periods2. What length is ideal? as usual, opinions vary and evidence is fragmentary: some observational studies say that 52 minutes of work and 17 minutes of rest is optimal3, but most probably it will depend on what you are personally used to and the nature of the task you’re doing (e.g., how mentally taxing it is). In this sense, using the “Pomodoro technique” is a nice starting point to get this habit going, since it times not only your focused work periods, but also your rest periods (micro-breaks becoming procrastination rabbit-holes is also a common danger to watch out for, according to many PhD students I’ve heard from).

- Moving: Research on breaks also suggests that moving our bodies during breaks both helps us physically and stimulates our cognitive capacity and creativity4. In the end, our brains need sugar and other nutrients to function – hence stimulating blood flow will help our mental performance after the break. Try doing stretches, pushups or squats, or simply go for a walk to the water fountain (or even brisk-walk around the block5) . I have found that my brain resists taking these breaks (I could write another paragraph during those precious five minutes!), but then many good ideas come precisely when I get off my chair.

- Social: The work of a PhD is often solitary, and many doctoral students self-identify as introverts – thus making solitary breaks quite common. Yet, if you have access to a research team around you, or some other set of people you can take the break with, research seems to support the value of social or collective breaks6… especially if you can choose whom to take the break with (remember self-determination theory? autonomy is important!). Social breaks help us focus on something other than the task we were doing (see #5 below), or get another perspective on our problem. In my personal experience (e.g., during “writing camps” for doctoral students that our department organizes), this kind of “synchronized breaks” are very powerful: there is something ancestrally satisfying in doing something along with others in the same room at the same time (and stopping it at the same time as well)… Something like a group ritual. Of course, the current COVID pandemic is making these social practices a bit more challenging – but not something that a bit of ingenuity and creativity cannot overcome. For instance, I have heard from doctoral students hundreds of kilometers apart, who still go for a run “together” (by calling each other on the phone and running, each one in their own place), to keep themselves energized and socialized through a long day of work.

- Natural: Yet another strand of research on breaks focuses on whether the setting of the break has an effect on its effectiveness. One of the most researched aspects is the benefit of outdoors natural settings7 (or even small natural elements like having plants in your office8). Being in (or seeing) natural settings and elements like trees, water streams or plants, has more restorative benefits than man-made ones like your typical office building. Take advantage of that nearby park, if you have one. Plus, outdoor natural settings tend to be safer from the point of view of COVID as well!

- Fully detached: Because our technological marvels make it possible to continue working anytime, anywhere, the temptation to “just check a few emails” or do some other (work-related) menial tasks while taking a break is strong. However, researchers have shown again and again that detaching ourselves psychologically from work is as important as taking ourselves physically off our chairs7. If you can, avoid doing other work tasks or talking with labmates about the same problems you were working on. If you cannot, at least talking with others might give you new ideas and perspectives on the problem you were stuck in.

Criteria #6: Varied breaks

Another important aspect mentioned in Pink’s book is to introduce a bit of variety in your breaks. Doing different kinds of break activities (which have different benefits) could be useful at different moments during the day.

- Meditation (be it a simple body scan, paying attention to breathing or eating mindfully) can be an excellent source of calm and focus, and does not need to take more than a few minutes. Plus, mindfulness may have many other long-term benefits9. Personally, I find this kind of break especially useful when I have to change gears from some other complex project that makes my mind swirl with thoughts or feelings. Even short meditations seem to help with calming down those overexcited trains of thought and focusing on the next task at hand (additional tip: writing down in a piece of paper some of those thoughts/feelings may also help our brains off-load and be sure all those “open loops” will not be forgotten).

- Breathe. Even without the meditative component, breathing exercises are a very powerful tool for accessing our nervous system, be it for calming ourselves or for boosting our energy. You can read entire books on the subject of how to breathe10, but I have found out that learning just a few simple breathing techniques can give you enough tools to enhance most of your breaks. You can use them to calm after stressful situations (e.g., the square breathing practice), to fall sleep, become more awake, or to regain balance (see the three breathing techniques mentioned in this TED talk by yoga teacher Lucas Rockwood).

- Positive emotions. As we saw in a previous post about engagement in our happiness at (research) work, regularly activating emotions like humor, awe or joy is essential to our wellbeing. And breaks are the perfect moment to do so. Use your favorite uplifting song, or share some jokes with a labmate. We can also get an extra motivation boost if, just before coming back to the task at hand, we remind ourselves about our larger purpose.

- Lunch. Although snacking/eating during breaks is not as crucial as other factors mentioned above, we still need nourishment to function at the best of our ability. Thus, skipping lunch to continue working is not an option. It is actually the perfect opportunity to put in practice many of the other tips we’ve seen: if possible, have lunch socially (especially, with people you like), away from the office/lab… you can even do it in a nearby park or under a tree, if you have one nearby. Do not let this opportunity to feed yourself, physically and mentally, pass unnoticed!

- Naps. The science of napping effectively could itself occupy a whole post. Here, just the highlights: napping has a host of benefits, from increased alertness, attention, memory, reasoning and problem solving capacity (plus the physical benefits like better immune system and health). Length-wise, shorter “power naps” of 10-25 minutes are most efficient, as they pack most of the benefits and avoid post-nap grogginess. The “after lunch dip” in attention that most people experience (see our previous chronobiology post) is probably the most natural moment to nap. Also, there seem to be benefits to the regularity of napping (e.g., doing it every day, rather than only occasionally). If you are into caffeinated beverages, some people like the “nappuccino”, in which you take a coffee just before the (short) nap so that, when you wake up from it, you get the alertness benefits of both the coffee and the nap (caffeine takes about 20 minutes to kick in). Yet, despite all the (average) benefits of napping, be careful with these siestas if you are prone to insomnia or have trouble sleeping (as naps decrease adenosine pressure on our brains, which is critical to fall sleep at night11).

Phew, that was a lot of information! I hope this intense tour of the science of resting and recovering from work was useful. Yet, do not overthink it, or try too hard to have “the perfect break”: probably this, like many other things in life, is an issue of “diminishing returns” (20% of the tips and tricks I mentioned will get you 80% of the benefits of a good break). Worse, the obsession with tuning your breaks can become yet another source of procrastination.

So, if you have been working hard for 25 minutes, an hour, or whatever time you had set for yourself, get off that chair. Take “a short walk outside with a friend during which you discuss something other than work.”1.

You can thank me later.

Do you have any other “break tips” that have worked for you, which you would like to share with fellow PhD students? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header photo by Georgios Kaleadis via Flickr

-

Pink, D. H. (2019). When: The scientific secrets of perfect timing. Penguin Press. ↩︎

-

Flanagan, J., & Nathan-Roberts, D. (2019). Theories of Vigilance and the Prospect of Cognitive Restoration. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 63(1), 1639–1643. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181319631506 ↩︎

-

I haven’t been able to find a peer-reviewed, academic reference for this. It seems that the study was done by the Draugiem Group, using data from the DeskTime app, as described in this post by one of the members of the company running the study. ↩︎

-

Frith, E., Ryu, S., Kang, M., & Loprinzi, P. D. (2019). Systematic review of the proposed associations between physical exercise and creative thinking. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(4), 858–877. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v15i4.1773 ↩︎

-

Wu, L.-L., Wang, K.-M., Liao, P.-I., Kao, Y.-H., & Huang, Y.-C. (2015). Effects of an 8-Week Outdoor Brisk Walking Program on Fatigue in Hi-Tech Industry Employees: A Randomized Control Trial. Workplace Health & Safety, 63(10), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079915589685 ↩︎

-

Kim, S., Park, Y., & Niu, Q. (2017). Micro-break activities at work to recover from daily work demands: Micro-Break Activities. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2109 ↩︎

-

Sonnentag, S., Venz, L., & Casper, A. (2017). Advances in recovery research: What have we learned? What should be done next? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000079 ↩︎

-

Hall, C., & Knuth, M. (2019). An update of the literature supporting the well-being benefits of plants: A review of the emotional and mental health benefits of plants. Journal of Environmental Horticulture, 37(1), 30–38. ↩︎

-

Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). Altered traits: Science reveals how meditation changes your mind, brain, and body. Penguin. ↩︎

-

Nestor, J. (2020). Breath: The new science of a lost art. Penguin UK. ↩︎

-

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: The new science of sleep and dreams. Penguin UK. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.