POSTS

Quickie: How many PhD students are anxious or depressed (or will drop out) worldwide?

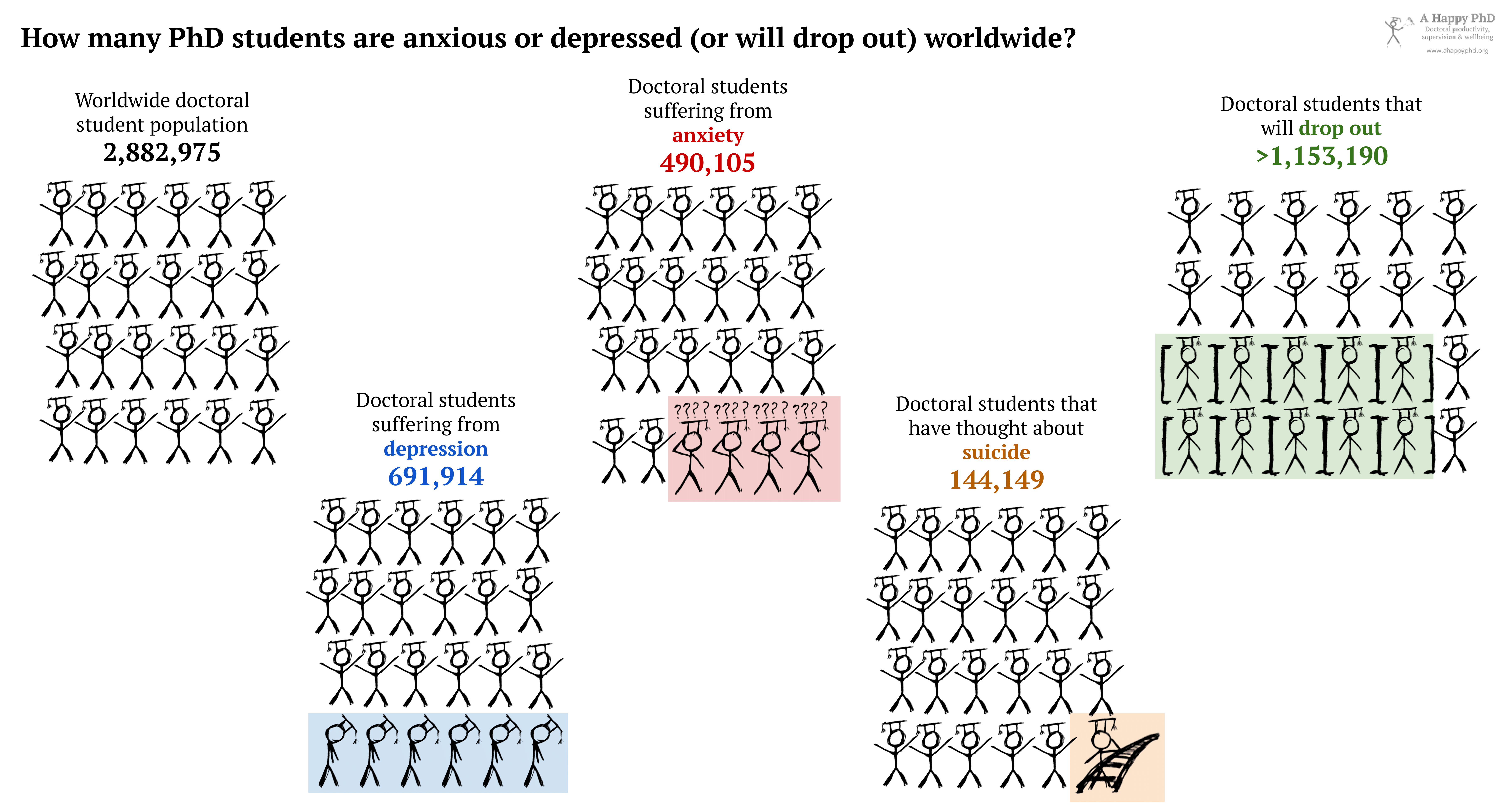

by Luis P. Prieto, - 6 minutes read - 1250 wordsOne of the catalysts that kickstarted this blog was the realization that PhD students are at a higher risk of mental health problems than other students and professionals. Yet, how bad is the problem really? Exactly how many PhD students are suffering from depression or severe anxiety right now? How many will drop out? In this quickie post, I pull from the data of a few recent studies to give a concrete, numeric answer guesstimate to these questions.

For the past two years, we have been writing in this blog about the mental health challenges of doing a doctoral degree, risk factors associated to them, and potential practices and solutions to face them. But I have never really written about the scale of the problem: how many people suffer from these challenges? is it hundreds of people, thousands, tens of thousands? This is a notoriously hard question to answer, not only because mental health is still a taboo subject in many cultures, but also because good estimates of the number of doctoral students worldwide, were unavailable…

… until now. Several recent studies and scientific reports have finally given us the pieces of data to peg a number to this everyday drama of doctoral education.

The numbers

What percentage of doctoral students are anxious? A recent systematic review looking at mental health issues in the doctorate estimated the prevalence of anxiety problems among doctoral students at 17%1. This figure may be lower than some other studies I have seen2, but it probably is a less biased estimate… Still, that is one in every six students!

What percentage of doctoral students are depressed? In the same study, they also estimated the prevalence of depression among doctoral students at 24%1. That is almost one in every four students!

What percentage of doctoral students have thought about suicide? I had not even thought about answering this question, but I have heard of cases of suicide during the doctorate. The same review also tried to look at suicidal ideation (i.e., considering ending one’s own life), but the data from the studies was too small and heterogeneous1: the prevalence in the reviewed studies range from 2-12%. Hence, maybe 5% is a reasonable, kinda conservative guesstimate.

What percentage of doctoral students will never finish the PhD? Classic texts on the topic of doctoral dropout (or doctoral attrition, as it is often called in the literature) mention dropout rates in the 40-60% range3, with 10-20% higher rates in online/distance doctoral degrees (that’s 50-80%!)4. For triangulation, a more recent study in Belgium gave out a probable 38-45% of attrition5. Hence, estimating that 40% of doctoral students that start a PhD will never finish it, is not unreasonable (actually, I’d say it is very conservative, given that most institutions around the world will have less resources and will be less concerned about their doctoral students dropping out than the aforementioned Belgian university).

How many doctoral students are out there? A recent report for the UK Council for Graduate Education estimates that 2,882,975 doctoral students are enrolled in doctoral programs worldwide6. The author of the report acknowledges that this is also a conservative estimate, since there were several countries (and institutions) that were not accounted for in his data.

Putting these numbers together, we can thus give a (conservative) answer guesstimate to the questions we posed at the top of this post:

- 490,105 PhD students are suffering from anxiety right now.

- 691,914 PhD students are depressed right now.

- 144,149 of current PhD students have thought about suicide.

- 1,153,190 of current PhD students will not finish their studies.

Wow.

A hopeful note

Now that I see those numbers, this may be the most depressing post I’ve ever written here. Yet, despite the huge numbers, not everything is doom and gloom. Each of us, no matter how anxious or depressed (or convinced to drop out), still has free will. We still have a choice. Many options, actually7.

What these numbers show is that this is a real, very common problem. It is not an easy problem to solve (or someone would have solved it already); it is a global problem with many factors feeding into it – economic, social, institutional, personal… So, if you are part of one (or more) of these collectives, know that you are not alone. Many others are also suffering, and your response to this suffering is not unreasonable. There is nothing inherently wrong with you.

Once we realize that our situation is not that rare, the next step is to realize that it is OK to talk about it. Talk about it with whoever you trust: with your friends and family, with your colleagues, with your supervisor. Most universities and institutions have services or resources for counseling their students – use them! Seek professional help. It is not a sign of weakness to seek help.

Finally, know that there exist solutions for these problems, from big evidence-based therapy approaches like cognitive-behavioral therapy8 (CBT) or acceptance and commitment therapy9 (ACT)… but also small everyday gestures and practices (like connecting with our purpose to do the PhD, or getting out of our heads and continuing to do the work).

Many have suffered from similar problems… and have been able to get out of them, finish their PhD, and learn a lot about research, academia and themselves. Even with extremely bad luck or circumstances, you can do it. You don’t need to be a genius with great luck to do a PhD.

Take care, and see you next week!

Were you surprised by the numbers I have given? Did you think they would be lower, or higher? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header image via Hippopx.

-

Satinsky, E. N., Kimura, T., Kiang, M. V., Abebe, R., Cunningham, S., Lee, H., Lin, X., Liu, C. H., Rudan, I., Sen, S., Tomlinson, M., Yaver, M., & Tsai, A. C. (2021). Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph.D. students. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 14370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93687-7 ↩︎

-

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282–284. ↩︎

-

Bair, C. R., & Haworth, J. G. (2005). Doctoral Student Attrition and Persistence: A Meta-Synthesis of Research. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (Vol. 19, pp. 481–534). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2456-8_11 ↩︎

-

Terrell, S. R., Snyder, M. M., Dringus, L. P., & Maddrey, E. (2012). A grounded theory of connectivity and persistence in a limited residency doctoral program. Qualitative Report, 17, 62. ↩︎

-

Wollast, R., Boudrenghien, G., Van der Linden, N., Galand, B., Roland, N., Devos, C., De Clercq, M., Klein, O., Azzi, A., & Frenay, M. (2018). Who Are the Doctoral Students Who Drop Out? Factors Associated with the Rate of Doctoral Degree Completion in Universities. International Journal of Higher Education, 7(4), 143. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v7n4p143 ↩︎

-

Taylor, S. (2021). Towards Describing the Global Doctoral Landscape. UK Council for Graduate Education. http://www.ukcge.ac.uk/article/towards-global-doctoral-landscape-475.aspx ↩︎

-

For an interesting approach about how to come to discover these options, from a life and career advice perspective, see Burnett, W., & Evans, D. J. (2016). Designing your life: How to build a well-lived, joyful life. Knopf. ↩︎

-

Burns, D. D. (1981). Feeling good. Signet Book. ↩︎

-

Hayes, S. C. (2005). Get out of your mind and into your life: The new acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.