POSTS

The four disciplines of executing your PhD (book extract)

by Luis P. Prieto, - 18 minutes read - 3813 wordsVery often, the myriad of obligations, additional tasks, jobs and activities in our daily lives block us from making progress in our most important goals (like finishing that doctoral thesis!). This is especially true of part-time doctoral students that have a day job to make ends meet, but even full-time students face this challenge. Our behavior needs to change, but we can’t find what to change (or the energy to do it). In this post, I extract from the book The Four Disciplines of Execution a methodology to face the challenges of making progress towards our important dissertation milestones, despite this everyday whirlwind holding us back.

Have you ever started a week with big plans for how you will tackle the next big rock of your thesis (you may have mapped all of them, even), but then… “shit life happened”: a surprise meeting with your lab head and the unexpected tasks derived from it; a family crisis at home that wiped out a whole morning; preparing the classes you teach took longer than expected… By the end of the week, you have been working like crazy, but nothing that really advances your thesis has happened.

Many of the doctoral students I’ve spoken with, who have difficulties making progress, report this kind of experience (and I can tell you that this does not go away once you are a doctor!). We often face situations where “something important needs to get done against the backdrop of many competing obligations and distractions”1. The 4 Disciplines of Execution (4DX)2 describes a method developed by a “big business” consulting firm to help companies and public institutions innovate, especially when innovations require that teams change their behavior to drive qualitatively improved results. In case you don’t want to wade through 300+ pages of business/consulting prose and case studies, below you have an extract of the book’s key ideas, customized for PhD students in a situation like the one I painted above.

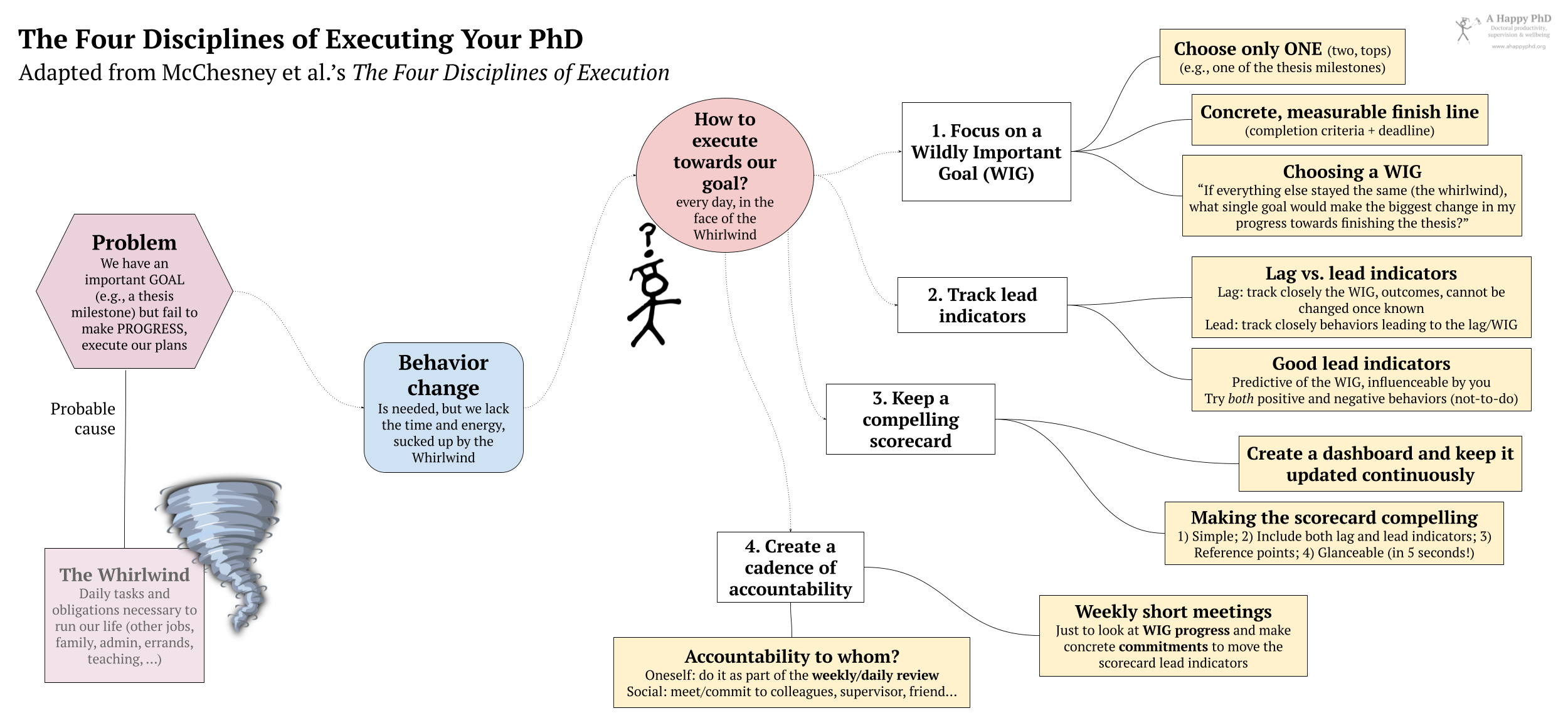

The Whirlwind

The book nicely sets up the problem that the 4DX method attempts to overcome with the metaphor of “the Whirlwind”: those everyday activities that are necessary for the running of a business (or our lives, in the case of an individual), but are not key to the change we want to make, to the big goal we want to achieve. It is not that these things are uniformly unimportant: sometimes they are at the core of one of our job titles and/or they are obligations (personal or professional) we have acquired with people we do not want to disappoint. Important or not, very often these “whirlwind activities” are urgent, time-sensitive. Some doctoral students have told me about how they spend their days “putting out fires” but never make progress. This urgency is what makes it so difficult to overcome the whirlwind and get these new big goals (i.e., write that paper that is central to our dissertation) done.

There are as many examples of whirlwind activities as there are doctoral students: complicated family situations that periodically generate “emergencies”, jobs unrelated to the PhD that spill over their intended workload, collaborations with other research teams (which started casually and now have become a burdensome obligation), research projects that pay our PhD salary but are not that related to our PhD topic, teaching that is part of our doctoral obligations, random things our supervisors ask us to do… the list is endless. Sometimes, even things that are related to our thesis should be put into this whirlwind category, like randomly scanning and reading for new research papers on our topic, or copyediting an early draft of a paper (see a recent post by the Thesis Whisperer for some more examples of this “PhD busy work”).

Looking at our everyday whirlwind may put us in a fatalistic mood. There seems to be no escape from it. A lot of our energy will go into this whirlwind (estimations in the book put it at 80%, but this probably varies a lot). Are we thus condemned to this state of affairs, to never achieve our key dissertation milestones (which often do not constitute a part of this whirlwind)? or is there a way to apply our energy and pressure in the right points, that gets us better results?

That’s what the “four disciplines” below try to guide us to find out.

Four disciplines of executing towards a (dissertation) milestone

Discipline 1: Focus on one Wildly Important Goal

The first step in overcoming the whirlwind is to find our focus. As authors note in the 4DX book, one cannot drill a hole into a piece of paper by applying even pressure everywhere – we need to use a single finger or, better yet, a pen. Similarly, the sharper our focus, the better. The main assumption behind this discipline is that we are limited: limited in time, in energy, in attention… If we are in the kind of “whirlwind situation” I described above, we will not be able to achieve 20 additional goals on top of it, or change 20 different behaviors to get better results. We need to focus, focus, focus!

In practice, this means that we must define one (two, at most) Wildly Important Goal (WIG). This is one key, ambitious goal that will make a big difference to our aspirations. For a PhD student trying to make progress in their thesis, this WIG would probably be one of the big milestones defined when we mapped out our PhD journey. If we have double-checked the map/milestones with supervisor(s) and/or other colleagues, there are good chances that the next milestone is a good candidate for our WIG.

Yet, how we formulate our WIG is also important. The WIG needs to be a concrete, measurable finish line. However, the goal formula provided in the book (“from X to Y by When”), which works wonders for a business with repetitive activities, may not work for a doctoral dissertation where activities are often, by their very nature, novel and non-repeatable. In this case, defining the milestone, its completion criteria and the deadline would probably work better. For instance, “Submit a good paper to journal X, by the end of the semester”, or “Run my experiment with 100 participants by date D”.

Some PhD students (and more experienced researchers) may also have trouble choosing a WIG, either because the map of the thesis is not clearly laid out, or because there are many important research directions or avenues of activity they face. Here, rather than asking “what area is most important?” (at that point, all areas may seem important, that’s why the whirlwind is a whirlwind!), sometimes it is more useful to ask: “If everything else stays the same (the whirlwind), what single goal would make the biggest change in my progress towards finishing the thesis?" (or tenure, or whatever objective we have).

To better understand this 4DX process, let’s look at a realistic example. Let’s take Oliver, a humanities doctoral student struggling to make progress in his thesis about the history of design during the dark ages. After talking with his supervisor about the milestones of the thesis, they agree that he has read enough sources already and that Oliver needs to finalize his content analysis and crystallize the lessons learned from it into a journal paper (submitting this paper to a good journal in the area of design history has been identified as one of the milestones of the dissertation). Although Oliver is almost finished with the analysis, he has spent months struggling to find time and energy to write the paper, in part due to his working as a research assistant for another (unrelated) research project. His supervisor agrees to provide an estimation of the probability that Oliver’s draft will be accepted (or rather, not rejected) at the target journal (on which she has published several times), so Oliver defines his WIG as “Submit a draft rated as 70% acceptable for our target journal, by December 1st” (three months from now). We can see how this WIG is both very concrete and ambitious (trying to finish in three months what he had failed to achieve in the whole previous semester).

Discipline 2: Track lead indicators

OK, so now we have a concrete and ambitious goal but… how to achieve it? Just defining a nice goal will not magically make the whirlwind go away, so if we failed before, will we not fail again? As they say, doing the same thing and expecting different results is insane, so they key to achieving this novel, ambitious WIG is to change our behavior. To do that, we define indicators of such behavior change, and we track them.

The second discipline of 4DX brings another interesting concept: the distinction between lag and lead indicators of success. A lag indicator is an important measure of our success: for a company, it may be this year’s revenue; for a PhD student, it may be “my paper got accepted in this very good journal”, or “I finished my review of literature”. Often, these lag indicators are more or less synonymous with the WIGs, with the big milestones we define for our thesis. The problem with lag indicators is that we get to know them after the behaviors that caused them have passed (hence the name, “lag”). Thus, we cannot really change their value. Not for this period, at least. Thus, although they are important, they are not useful for our day-to-day operations to achieve the WIG. Lead indicators, on the other hand, precede the achievement and are thus a more useful diagnostic tool for day-to-day execution (i.e., to know if we are going in the right direction – and course correct if needed). A good lead indicator should be predictive of the WIG: if we do good in them, we are highly likely to achieve the WIG. Good lead indicators are also influenceable: they are directly (or mostly) under our control, rather than dependent on chance or other people’s actions. In other words, lead indicators often track the behaviors that need to change for us to achieve the WIG (despite the whirlwind that is still raging). An example of a lead indicator for sales in a company (the lag indicator) could be the number of calls made to prospective clients (the behavior we hope will eventually drive sales). For a PhD student seeking to finish their review of literature, it may be “hours spent in a distraction-free place reading” (again, focus on a behavior that is challenging but we think predictive of success). Would “number of paper summaries written today” be a good lead indicator? Not sure – it rather measures the outcome, not the behavior (so it looks more like a “more frequent lag indicator”), and it depends on external factors (e.g., the length of each paper). Defining good lead indicators is not always easy!

The second discipline of the 4DX method thus asks us to not only track a few good lag indicators of the WIG we defined in the previous discipline: it asks us to brainstorm and define some good (i.e., highly predictive and influenceable) lead indicators towards that WIG. Defining these lead indicators normally requires contextual knowledge: of our environments, our behavioral pitfalls, our weaknesses… an external actor (a supervisor or coach) cannot really impose them (although people that know us well may give ideas for behaviors that derail us). Then, we will need to track them, day in, day out. This also means that good lead indicators are often frequent enough that tracking them daily (or weekly at most) makes sense. Oh, and one last tip (not taken from the book, but adapted from somewhere else3: We should consider not only positive lead indicators (representing new behaviors or habits that will help us achieve the WIG) but also negative ones (behaviors to stop, because they lead to spending too much time in our whirlwind or other distractions).

Once we have set lead indicators (i.e., behaviors) for ourselves and start tracking them, we will be more engaged in the work. Not just the “whirlwind” work, but also the very important work of our WIG. And once we see the lag measures go up after the leads increase, we will engage even more.

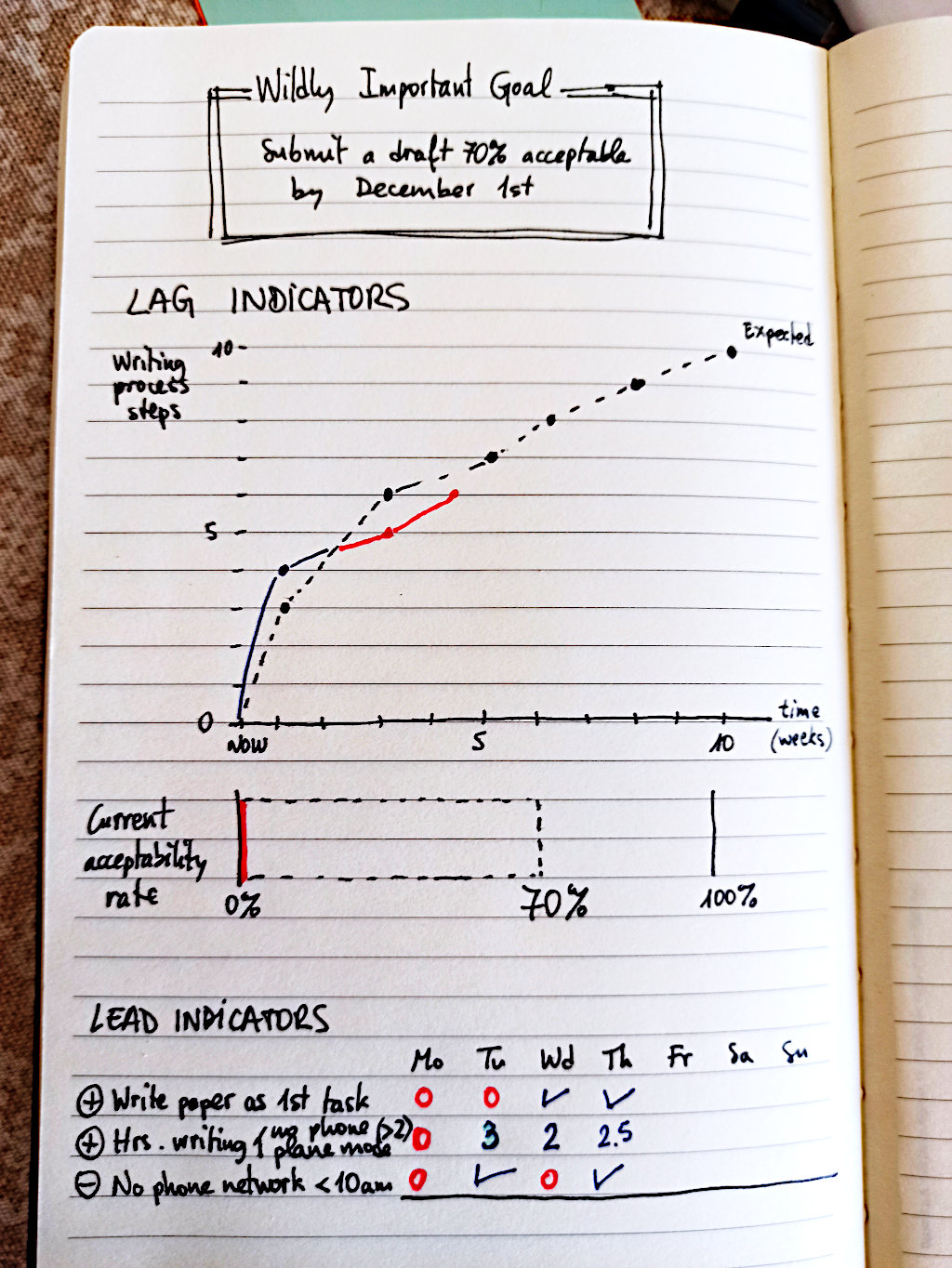

Let’s see how this second discipline would work for our doctoral student example. Taking directly from the definition of his WIG, and the writing process we defined in a previous blog post, Oliver defines two main lag measures: “Writing process steps completed” (a scale from 1-10, as there are ten steps in the process), and “estimated acceptance chance of the current draft” (to be asked of his supervisor whenever a new complete draft is available). Defining lead measures proves a bit trickier, though: Oliver discards the idea of “words written per day” (which is still rather an outcome, not a behavior); “time spent writing” is maybe better, but a bit vague (he has spent many afternoons “writing”, just staring at the blank screen until the urge to check the phone is too strong). Upon reflection (and some journaling), he has noticed that his whirlwind (the unrelated research project that pays his bills, but also some digital distractions like TikTok-ing) catches him from very early and multiple times throughout the day (he checks his email first thing in the morning, and dozens of times due to the email notifications in his phone). He thus defines three lead indicators, in the hope to develop new behaviors that take him closer to what is important for him:

- Spending some time writing as my first task of the day (binary)

- Do not connect the smartphone’s networks until 10am (binary, negative)

- Hours spent writing my paper in a distraction-free place, with my phone and computer in plane mode (scale)

Note how this last lead indicator already has several behaviors embedded in it, forming a sort of ritual (go to a particular place, and put both phone and computer in plane mode).

Discipline 3: Keep a compelling scorecard

The third discipline is about engagement: how can we remain engaged with achieving our WIGs, among the myriad of everyday tasks in our whirlwind? Taking a page from street basketball, the authors of the book note that “people play differently when they are keeping score”. To drive engagement, they suggest to not only gather data every day about the lag and lead indicators towards our WIG… but also to create a compelling scorecard and to keep it, updated continuously, in a highly visible place.

Today, in the age of data science and analytics, the idea of keeping some kind of leaderboard or scorecard is, of course, not new. Many areas of research (including learning technologies, where my own research lies) have noted the potential of these data-based scorecards (“dashboards”, we call them4) to inform and engage people. The book provides several guidelines for what makes such scorecards compelling: 1) Keep it simple; 2) Include in it both lag and lead measures (and nothing else!); 3) The board should tell whether we are “losing or winning” (i.e., it needs to include reference points or expected values, so that we can easily see whether we are going according to plan or we need to step up our game); and 4) It should be so clear that we can tell at a glance if things are going well or not (the authors propose a “five-second rule”: if you need more than 5 seconds to know what’s the status, simplify more!). Designing the scorecard, implementing it, and keeping it updated may take some effort, but if it is simple enough, it should be doable even amid our whirlwind.

Coming back to our running example, Oliver decides that (since many of his distractions and entry points into the whirlwind are digital) he is going to go “old school” on this. He will keep track of his lag and lead indicators, at the end of each workday, in the pen-and-paper journal he carries everywhere. The lead indicators will be recorded in a simple table, with red or blue pen, depending on whether he met expectations that day or not (e.g., he wants to spend a minimum of two hours working undistracted on his paper). The lag indicators will be painted over a simple timeline graph, where he has painted his expected progress until completion on December 1st. Oliver’s scorecard could look like this:

Discipline 4: Create a cadence of accountability

After three disciplines preparing the ground, this is where the execution really happens. One of the key problems when we set out to achieve a goal (but also face a whirlwind) is that, at some point, our motivation will falter and the goal will be forgotten in favor of the urgent day-to-day whirlwind matters. We need to hold ourselves accountable for really achieving the lead indicators we have defined, day in and day out. How do we do that? Holding a periodic meeting where we explicitly revise the scorecard to check whether we are on track to achieve the WIG (hence called WIG meetings, in the book) and make concrete commitments to move the lead indicators so that we achieve that WIG. The word “cadence” in the discipline’s name is also important: these WIG meetings should be held frequently enough so that we never forget about the WIG (the book recommends at least doing it weekly, and sometimes even daily).

A WIG meeting should be short, and it should not feature any “whirlwind matters”, just about the WIG and how to achieve it. In the meeting, two questions need to be addressed:

- What were the previous week’s commitments and how did they move the scoreboard?

- What are the one or two most important things I can do in the next week (outside the whirlwind) that will have the biggest impact on the scoreboard? (and make explicit commitments to do them)

One key difference between the companies/institutions in the book and a PhD student trying to apply this method, is that in companies normally the WIG is shared by a team and thus this discipline is all about team accountability, and about making commitments to each other. Yet, as you very well know, a doctoral dissertation is mostly an individual achievement, so most PhD-related WIGs will not really be shared by anyone else. How can we then adapt this discipline for the individual PhD student?

- If I am a person that has no problem in keeping promises to myself (what Gretchen Rubin calls an Upholder5), then the solution is easy: the WIG meetings are fully aligned with the idea of doing daily and weekly reviews that we have repeatedly recommended in the blog. These reviews are basically “meetings with oneself”, and I could just add a “WIG part” to my reviews in which I revise whether I did the commitments from last week, revise my scorecard, and make (and write down!) my commitments and behaviors to move the scorecard in the following week.

- If I (like many others) tend to find excuses and ways to break the promises I make to myself, then creating some sort of social accountability is still the best way to sustain your motivation to strive towards the WIG. Potential workarounds include:

- Having the WIG meetings (and making commitments) to a spouse, friend or colleague we trust (who accepts to push us if we falter in our motivation)

- Having the WIG meetings with our supervisor (if our relationship with them is good enough and they agree to spending some time that way)

- Creating a doctoral WIG group with fellow PhD students (similar to a doctoral writing group6), in which each of us reviews the work towards our respective (different) WIGs, but still make commitments to each other to engage in behaviors and strategies that will move our particular scorecard

In our running example, Oliver reflects that he quite often squirms out of the commitments and promises he makes to himself – putting commitments (or just pleasing) others first. Indeed, that’s probably why he’s caught so hard in his whirlwind! He thus tries to exploit his weakness for social accountability to implement the WIG meetings. Since he does not have trusted colleagues around him regularly, he decides to ask his supervisor (with whom he has a quite good relationship) whether he could attend a weekly 10-15 minutes meeting (via Zoom/Skype, since they are not always in the office at the same time) to go over his scorecard and commitments to the WIG. Hoping this new effort will unblock Oliver’s progress, the supervisor accepts. In the first WIG meeting, Oliver commits to a) Put his phone in plane mode when he goes to bed; and b) Go to one of the university libraries set in a historic building (and known for its bad network coverage) for a writing session, at least two days a week.

The diagram below depicts a summary of the main ideas in this post:

Over to you

If you are a long-time reader (and practitioner!) of this blog, many of the tips in this post will not really sound new: weekly reviews, self-tracking, setting milestones and focusing on them… Indeed, if you are a member of our newsletter, you may have even drawn a detailed plan to achieve your next milestone. Yet, I believe this 4DX method ties these strategies up in a simple and powerful way, which is especially relevant for many struggling part-time doctoral students (or full-time students with additional obligations).

Give it a try.

Have you tried this 4DX method to achieve your thesis-related WIGs? Is it working? Do you have any PhD-specific tips or challenges you have faced when applying this method? Let us know in the comments section below, or leave us a voice message in the widget above the comments!

Header image by Wikimedia Commons.

-

Newport, C. (2016). Deep work: Rules for focused success in a distracted world. Hachette UK. ↩︎

-

McChesney, C., Covey, S., & Huling, J. (2012). The 4 disciplines of execution: Achieving your wildly important goals (Vol. 34). Simon and Schuster. ↩︎

-

Adams, G. S., Converse, B. A., Hales, A. H., & Klotz, L. E. (2021). People systematically overlook subtractive changes. Nature, 592(7853), 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03380-y ↩︎

-

Schwendimann, B. A., Rodriguez-Triana, M. J., Vozniuk, A., Prieto, L. P., Boroujeni, M. S., Holzer, A., Gillet, D., & Dillenbourg, P. (2016). Perceiving learning at a glance: A systematic literature review of learning dashboard research. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 10(1), 30–41. ↩︎

-

Rubin, G. (2017). The Four Tendencies: The Indispensable Personality Profiles that Reveal how to Make Your Life Better (and Other People’s Lives Better, Too). Harmony. ↩︎

-

Wegener, C., Meier, N., & Ingerslev, K. (2016). Borrowing brainpower – sharing insecurities. Lessons learned from a doctoral peer writing group. Studies in Higher Education, 41(6), 1092–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.966671 ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.