POSTS

Is Doctoral Productivity Bad?

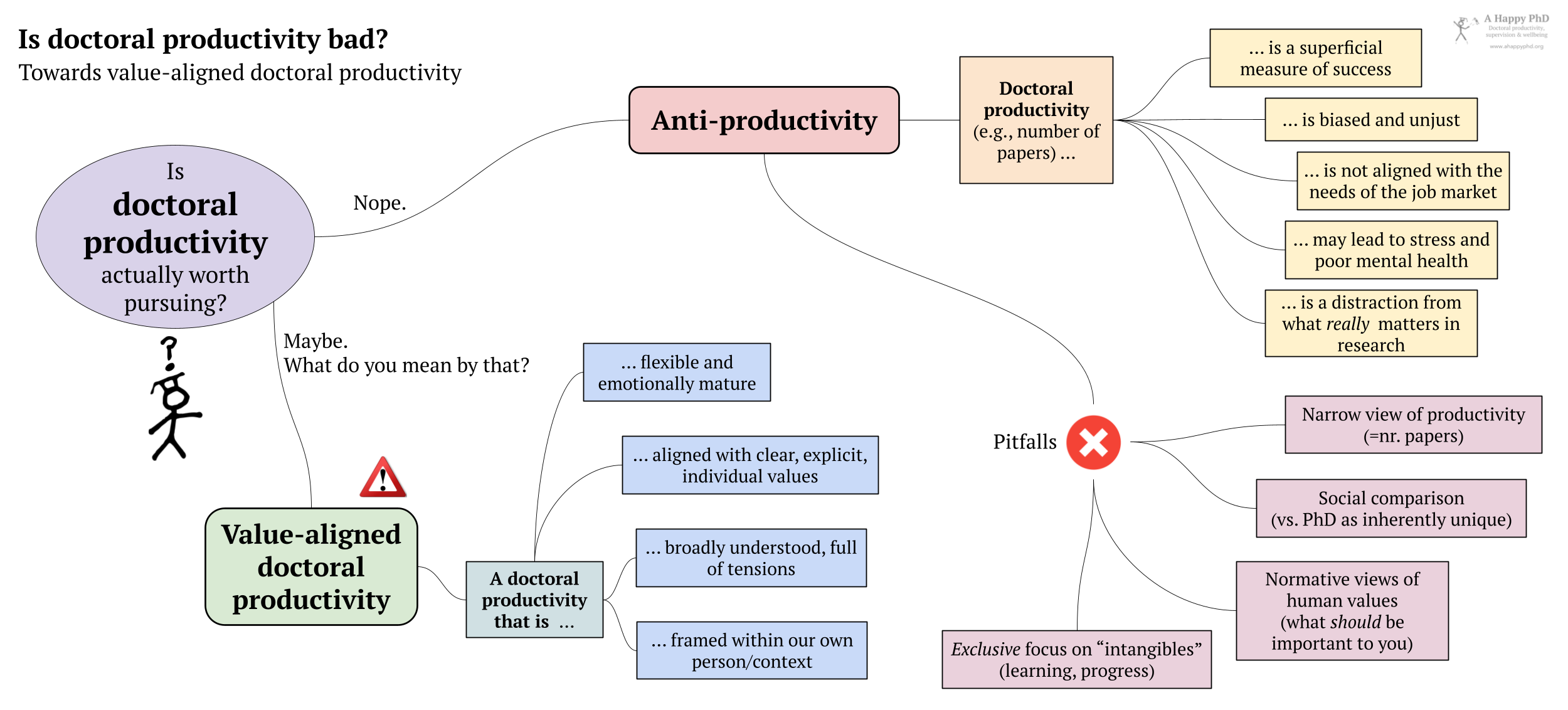

by Luis P. Prieto, - 11 minutes read - 2151 wordsIn this blog I have written a lot about doctoral productivity tools and advice. Yet, many doctoral students out there may also think that the focus on productivity is exploitative, dehumanizing, and counter to the very spirit of the scientific endeavor. Should we reject the quest for being productive altogether? Should we “quiet quit” our PhDs? This post tries to clarify what I mean by (doctoral) productivity, which may not be the “narrow productivity” view you find in certain research policy or journalistic articles about the topic. That way, you can decide whether it makes sense for you to follow my advice, or get it elsewhere.

When I started this blog back in 2019, a productivity geek with a mild case of burnout baffled by the challenges of supervising five doctoral students at the same time (and by the challenges they faced, it did not occur to me that someone might not want to be very productive.

Fast forward to 2024, through a global pandemic and with rates of mental health issues (including burnout) increasing even after the global catastrophe receded. In recent years, I have come across ideas against being highly productive (as a doctoral student, researcher and knowledge worker in general) quite a few times, from the (apparently pandemic-induced) “great resignation” to cultural phenomena like “quiet quitting”. This post then tries to answer the question that never occurred to me back in 2019 which many readers of this blog (struggling with their PhDs, maybe part of the so-called “Gen Z”) may have in their minds when reading all this: “is doctoral productivity actually worth pursuing?"

Since I was so ill-prepared to consider this question myself, I enlisted some help from the algorithmic fairies1 to help me understand some of the key arguments against productivity (both doctoral productivity and productivity in knowledge work more generally). These are the main productivity anti-theses I got (fun fact: the algorithm gave me one of my own blog posts to support some of the arguments!):

The arguments against (doctoral) productivity

Interestingly, the algorithm prefaced its responses with the fact that doctoral productivity is often defined as the amount and quality of publications (or other research output) that a doctoral student produces. This is in fact supported by recent scholarly articles I’ve read on the topic2, and with the way most people conceive “progress in the PhD” at the workshops we run with both doctoral students and supervisors. What are then some key arguments against a focus on this kind of productivity?

- Doctoral productivity (defined as above, in terms of number of publications, citations) is a superficial measure of success, that does not correlate with other important measures such as the development of research skills, critical thinking, the contributions’ originality, or the magnitude and rigor of the student’s contribution to knowledge.

- Doctoral productivity (again, as defined above) is not under the control of the doctoral student, and is heavily influenced by the academic and scientific publishing system’s inequalities, fashions and fads, etc. In other words, it is a measure that is biased and unjust.

- Doctoral productivity is not aligned with the needs of the job market, inside and outside academia. By producing too many PhDs3 that produce large quantities of (assumedly low quality) publications, the educational system is creating a situation in which very few PhD students can access stable academic jobs (e.g., tenure), and the rest are left with no academic job and a skillset that does not match the industry’s needs (even in highly innovative sectors where a PhD could be valuable/needed).

- A focus on doctoral productivity may lead to stress and poor mental health in general. Furthermore, the publication system fostered by the “publish or perish” culture may create an atmosphere of competition, isolation, and exploitation where doctoral students may feel insecure, unsupported, or undervalued – all of which are likely to impact doctoral students’ well-being negatively.

- The obsession with doctoral productivity (as defined above) is a distraction from what really matters in (doctoral) research, which is the learning of new scientific and critical thinking skills, and the progress of the research field. Further, it paints research activities as means to another end, be it a diploma, the prestige of the PhD title or a stable job in academia. Doctoral students should value research for its own sake, not as an instrument to other ends.

Pitfalls of anti-productivity thinking

To be honest, I kinda agree with all the anti-productivity arguments above… as long as we preface the focus on productivity with the word “excessive” (e.g., “an excessive focus on doctoral productivity…"). The obsession with productivity, like any other addiction, can be quite harmful for ourselves and for the research system we wish so hard to become a part of. However, when I see those anti-productivity arguments thrown around, I sometimes sense that people create a caricaturesque “productivity strawman” that not so many people (even the productivity geeks like myself) really fall into. Indeed, having an excessive focus on anti-productivity as per the arguments above can also present its own pitfalls and dangers:

- The anti-productivity arguments tend to target a “narrow view” of doctoral productivity (i.e., simple formulas like productivity = number of publications in X kind of venue), which is nevertheless very common in many research evaluation and policy systems (for example, the Spanish system still largely works like that), which in turn engender its own unethical practices and ways of “gaming the system”. I think there is now a growing consensus that (doctoral) productivity is multifaceted2.

- Both the “narrow productivity” measures in some scientific systems and the claim that the success in the doctoral process should be measured in some way that is inherently fair, rely on social comparison (i.e., comparing doctoral projects with one another). I have come to believe that such comparisons (no matter what metrics we use) are impossible or meaningless, given the uniqueness of each research question, of doctoral students and of the process and context they do the research on.

- Several of the anti-productivity arguments above rely on normative views of human values (i.e., we can tell people what they should care about, be it learning or scientific progress). The more I read about (and research, in my modest way4) cross-cultural psychology and related fields of research, the more I have come to believe that people value what they value, and telling them they should consider other things important, is useless at best, and a form of totalitarianism at its worst.

- Some of the arguments rejecting doctoral productivity, especially when taken to extremes, seem to have an exclusive focus on “intangibles” (i.e., things that are very difficult to measure, like learning or scientific progress) which seems at odds with the scientific method and the overall goal of research as increasing our understanding of the universe. While the exclusive focus on “one/few imperfect metrics that can be measured” is probably a bad productivity measurement approach, saying “it should not be measured at all” can be even worse. Anti-productivity can be a form of experiential avoidance, if it leads us to dwell in our fears and impostor syndromes and not try to do the hard work needed to both discover new knowledge and get our research published.

Towards a value-aligned version of (doctoral) productivity

OK, then… if we dismiss the “narrow view” of productivity, but also the anti-productivity arguments taken to extremes, what do I mean by “productivity” when I write about it in this blog, the newsletter and in our doctoral workshops? I mean a productivity that is…

- … aligned with a set of values that are clear, explicit, and probably unique to each of us. Productivity is always a means, and we decide to what end – on the basis of what is important to each of us personally. For instance if I find a new way of writing my research papers that is both ethical (assuming I care about being ethical) and more efficient (e.g., it cuts the time it takes me to write the paper in half), then I can choose to spend half the time writing papers, and dedicating that spare time to being with my family (assuming I care more about spending time with my family than about writing papers). From a “narrow perspective” my productivity has not changed, but I am being more productive because I’m doing more of what I value more. This is similar to the philosophy that some authors call “Valueism”.

- … framed within our own person, history and context (i.e., what in some areas of research they would call “intra-subject”). Whatever experiments we do with trying to be more productive, it is meaningless to measure it in comparative terms with other people (that are in other fields, have other skills, and other research questions) – these experiments should always be “within-subjects” designs, i.e., compared with our own past selves (and considering our current context/situation, which can vary over time – I can tell you that being a parent has made my productivity constraints vastly different :)).

- … broadly understood and full of tensions. In line with point #1 above, because we value multiple things in life to different degrees (and this ranking of values drifts over time), we are bound to have value tensions (if we do more of one thing we value, we will do less of another thing we also value), as well as other inherent tensions in what we do, especially for work (e.g., time dedicated to our research vs. other areas of our lives, number of artifacts produced vs. the quality of each artifact, etc.). This is a fact of life that we need to accept and tackle face on, and it is one of the key challenges of most PhD students. Sometimes triangulating between multiple measures of productivity (vs. maximizing a single measure – and including but not limited to some socially-obtained measures, even if that somewhat contravenes point #2 above, there you have another tension ;)) and defining quotas/fences between different areas or kinds of work can help us navigate these tensions.

- … flexible and emotionally mature. A logical consequence of the tensions in point #3 above, is the fact that we will never be perfect at everything, not even at everything we consider important. We will have to make tradeoffs flexibly in the best way we can, depending on the context of each moment/situation. We will have to make choices about who to disappoint at certain moments (including disappointing ourselves). Thus, we need to accept this fact, disappoint some people sometimes, face the consequences, and try to move on towards the things we consider most important (try this exercise from our classic post on doctoral mental health to better understand what this means, if you feel stuck or self-sabotaging your efforts).

I hope these few notes help clarify what I mean by productivity, so that you can take in (if you agree this is a worthy goal) or reject (if you disagree) all the productivity writing that you can find here in the blog and newsletter. The figure below summarizes the main ideas of the post.

Stay productive… but even more importantly, make sure to know what you mean by “productivity”!

Header image by Bing’s Image Creator5.

-

To get to these arguments, I checked Bing AI with these two prompts: a) “What would be the main arguments of someone who does not believe doctoral productivity to be a worthy pursuit? Please cite the main authors and sources behind each argument” and b) “And what are some general public arguments against personal productivity, including modern post-pandemic phenomena like ‘quiet quitting’ or ‘the great resignation’?”. Then I have merged and synthesized the ideas from the responses, since the algorithm is not terribly good at separating overlapping ideas and arguments from one another. ↩︎

-

See, for example, a recent example in Corsini, A., Pezzoni, M., & Visentin, F. (2022). What makes a productive Ph.D. student? Research Policy, 51(10), 104561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104561 . In the authors’ defense, “productivity” was quantified not just by number of peer-reviewed publications, but also yearly citations to the student’s papers (as a proxy for quality) and number of co-authors (as a proxy for the size of the student’s collaborator network). ↩︎

-

Cyranoski, D., Gilbert, N., Ledford, H., Nayar, A., & Yahia, M. (2011). Education: The PhD factory. Nature, 472(7343), 276–279. https://doi.org/10.1038/472276a ↩︎

-

Prieto, L. P., Rodríguez-Triana, M. J., Dimitriadis, Y., Pishtari, G., & Odriozola-González, P. (2023). Designing Technology for Doctoral Persistence and Well-Being: Findings from a Two-Country Value-Sensitive Inquiry into Student Progress. In O. Viberg, I. Jivet, P. J. Muñoz-Merino, M. Perifanou, & T. Papathoma (Eds.), Responsive and Sustainable Educational Futures (Vol. 14200, pp. 356–370). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42682-7_24 ↩︎

-

The prompt I used was “Please draw me an expressionist oil painting of PhD students in labcoats, incessantly toiling at their work, while the forces of late-stage capitalism ominously crush them under their gears.” ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.