POSTS

Forget New Year's resolutions -- Do a Yearly Review instead

by Luis P. Prieto, - 19 minutes read - 3934 wordsIf you are like most of us, by now (end of February) your New Year’s resolutions will have fallen by the wayside. In recent years, I have stopped doing resolutions altogether. This post is about what I do now instead, heeding the advice of productivity systems and psychotherapy approaches: a yearly review. This post goes over my particular yearly review process, and how it can give your research motivation (and satisfaction with life) a yearly boost.

Out with New Year Resolutions, in with Yearly Reviews

Despite the post title, I don’t New Year’s Resolutions (NYRs) useless or baseless. People do them for a good reason. The “fresh start effect”1 is a psychological phenomenon in which we use salient temporal landmarks (the New Year, our birthday, or the start of a new week) to do a bit of mental accounting, put our past selves (and their foibles) in a different box, and try to be a “new us” that exercises more, has a better diet… or dedicates more time to the doctoral dissertation.

And yet, we fail to sustain NYRs2. Despite the wealth of information online about how to make NYRs stick, this situation hasn’t changed much in the last 30+ years. If anything, things may have gotten worse, with recent studies on the topic reporting that such NYR failure often happens within the first month3. Neither being flexible nor gritty seems to help, but the study noticed that many of the failed resolutions were rather abstract in nature.

Should we just ditch the whole idea of improving with the New Year? Not necessarily. Maybe the problem is not that we try to change… but rather the direction of change: we often choose these resolutions by borrowing other people’s goals or expectations (diet and exercise seem to be the most common), rather than things we really value ourselves.

What I propose you to do instead is a Yearly Review: in a sense, similar to the weekly reviews I do to focus and be intentional about the week ahead – in this case, with a focus on long-term direction and lifelong values, rather than tactical day-to-day actions. Indeed, taking a high-level look at what you do (and have done so far) is a key process in many productivity systems (like the popular GTD), and is often advised by productivity gurus (e.g., Tim Ferriss, Leo Babauta, Cal Newport). Further, the yearly review is not just about productivity: modern psychology has found that making such values explicit and connecting them with what we do day-in-day-out is key to avoiding mental health problems and leading a workable, intentional life that we are satisfied with4.

I can almost hear you say: look, it is the end of February now, this advice comes a bit late, doesn’t it? Maybe I’ll try it in ten months’ time…

Don’t fall for that voice that only admits change via the fresh start effect. January 1st is an arbitrary landmark, and other cultures have other dates (you can try the Bali Hindu New Year!). Indeed, I recommend to also use this high-level review process whenever a major life event shakes up our lives (e.g., we had a big meltdown, somebody important in our life died, etc.)… or whenever we decide that, from tomorrow on, we are going to finish that damned dissertation. The fresh start effect also works for made-up landmarks!

My Yearly Review process

Below, I describe in detail the steps of my Yearly Review. They have evolved over time to suit my needs, so feel free to tweak them or take just the parts that resonate – although I believe that its overall shape is important.

To do the Yearly Review, set aside at least two hours (if you can take a whole morning/afternoon, that’s even better) to do this exercise.

Step 1: Look at the past

First, we should take stock of the past year (or the time since we did the last review of this kind), in the fashion of an “agile retrospective”, as I do for my weekly reviews. I look at this past period through the lens of four questions: What went well? What would I do differently? What lessons have I learned? and What is still puzzling me? If you are a doctoral student, pay special attention to these questions and what happened this past year in terms of your doctoral research (what worked and didn’t work? what were the successes, the failures and lessons learned from them? what skills or research questions do you want to learn more about?). Even with this emphasis on work, I try to make the retrospective all-encompassing (what about our friends and family? our physical and mental health? leisure? there is more to our lives than just the thesis!). As a bonus gratitude practice, in my weekly reviews I do a “Three Good Things” gratitude practice (i.e., thinking about three good things that happened, for which I’m grateful). Here, in the yearly retrospective, I summarize “good things trends”: what things, people or places tend to appear again and again in my three good things. This will be important later on.

Given that we know our memory is often faulty or biased, we can aid ourselves to do this retrospective part of the exercise by revising our journal for the past year, or our calendar app (if that’s our main tool for time and task management). Only as a last resort, if we have nothing of the sort, we could go exclusively from memory. Personally, since I have a record of my weekly reviews in my journal, and later those reviews are summarized each quarter (i.e., every three months) in a similar fashion, I only need to revise four small quarterly documents to capture these yearly trends. Even if we only have the weekly reviews, revising 50-ish short documents will be faster than reading 365 journal entries. I also do use raw memory, taking a breath and thinking thrice what comes to mind for each of the questions above – but looking at timely records like my journal or my calendar helps me fight memory’s salience and recency biases.

Once we have written down these yearly trends (yes, do not just do this in your mind, or it will soon be forgotten), we can jot down initial ideas for how to project these trends to the coming year (making more time for the “good things”, avoiding or getting better at the things that didn’t work, applying the lessons learned to develop new habits, or find out more about our ongoing puzzles). We will use those in Step 3 below.

After the structured analysis of the past year, I like to close this retrospective step with a freeform reflection: about one page or less of stream-of-consciousness writing about this past year, mentioning important trends from the retrospective, but also my interpretations, hopes, fears and anything else lurking in my mind that has not had the opportunity to come out yet. A sort of last brain dump before moving on to the next year. Once I write this (very drafty) text, I like to highlight important keywords within it, and finally choose a title for the reflection, thus picking a sort of “theme for the past year”. Not sure why, but there is something satisfying and meaningful in picking that title, as if it were a chapter in the book of my life.

If we are really pressed for time, we could skip this whole Step #1 altogether – but I strongly recommend to, at least, do some kind of looking back to the past year, to gain closure and put it behind our backs. You could just think deeply and answer thrice each of the 4+1 questions above, or try other shorter retrospective processes like the one Tim Ferriss describes here. Looking at the past to learn where we come from is critical to start defining our future!

Step 2: What are you about?

“He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how,”

– Friedrich Nietzsche, via Viktor Frankl

The second part of my yearly review process is mainly a structured reflection about one’s core values. What do I mean by “values”? Quoting Steven Hayes, the creator of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), “values are verbs/adverbs, not nouns/adjectives. They are something we do (or how we do it)."4 That is, values are not goals, feelings, outcomes, or anything about achieving success (or failure). “Finishing the thesis” is not a value. “Cultivating curiosity and autonomy” is.

Personal values are a critical element missing in much of the productivity (and doctoral) advice I’ve seen thrown around. Yet, values are central in many modern psychotherapy approaches to motivate sustained (and effortful) day-to-day action in the face of challenges (especially, emotional challenges). The New Year (or whatever “fresh start” moment we choose to do this review) is a good time for this kind of reflection, to give a clear direction to our actions in the long run.

I do this values reflection top-down, from very general high-level values to more specific ones. Thus, first I use the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ)5, a questionnaire that places one within a space of 10 things that people value across cultures (e.g., autonomy, power, caring for those close to us, etc.). Basically, we can use this validated research instrument to get general sense of what matters to us the most. I have found this kind of knowledge about myself (and others) very useful for decision-making: for instance, when deciding to take up a new research project or collaboration, I can ask myself whether it resonates with my most salient values (e.g., if I value autonomy the most, will this project allow me to decide the direction we go, or will that be directed by others?). That is a good predictor of whether I will be satisfied with the project in the long run. NB: values do change over time, but the top/bottom values often are quite stable – and, hence, can be safely used for decision-making.

Then, to get a more specific view of what I am about (if no one would laugh or say it is impossible), I do a couple of exercises, taken from ACT4. The simplest (and maybe most powerful) one is to imagine one’s own funeral. Close your eyes, take a few deep breaths, and picture this: You have died after a living long life, and family and friends have gathered to mourn you. Write down what you fear people could say, if you were defeated by your struggles, your addictions, your worst inclinations – if you followed the path of avoidance. Make it, say, 8-10 sentences like “He was always distracted, never really there for me or our children.". Then, write down the opposite: what you imagine people would say of you, if you lived according to what you most value, if your purpose were evident, clear and manifest (note: this is not about all your goals being magically attained; your family/friends would talk more about how you did things, rather than what you did, like “He found his own creative way of alleviating the suffering of others”). Again, 8-10 sentences like this will probably suffice. Then, highlight what you think are the most important words in those two texts. Finally, try to summarize both texts into a short epitaph, something that would be written in your tombstone as a summary of your life, if well lived. This exercise might seem macabre, but I find it tremendously useful to cut through my own bullshit. Indeed, the results of this exercise can be useful for decision making right away: write down the epitaph into a piece of paper or index card, and keep it with you when you do your regular reflections, or when you are thinking about an important decision (should I take on this opportunity I’ve been offered? Should I give in and indulge in some temptation? If it does not resonate somehow with your epitaph, maybe you don’t need to).

As a second exercise, I try to look at my values in a more granular level, by listing my values in up to 10 different domains of life. This exercise, also taken from the ACT workbook4, looks at what kind of person we want to be, in:

- Marriage or intimate relationships

- Parenting

- Family relations (other than the above)

- Friendship and other social relations

- Our career or employment

- Our education and personal development

- Our leisure and fun activities

- Our spirituality

- Citizenship

- Our health and physical wellbeing

This per-area reflection would take the form of a few sentences, a paragraph looking more at how you want to act, rather than what you want to accomplish (e.g., “I would like to work creatively, in my own way and direction”). Don’t overthink this exercise too much, just free-write for a few minutes in each direction. The number of areas we examine is not necessarily important, nor its denomination. Choose labels that are meaningful to you, and group the areas in different ways if that is more meaningful to you (e.g., you could join the first four areas into a single area called “Social relationships”). Oh, and make sure that your doctoral dissertation (or your research) fits in one of these buckets, at least. The point here is to look at our lives from multiple perspectives, not just work, but also not just personal stuff. I also like to summarize the free-form text I just wrote into a few keywords, my core values in the area (like “Independence”, “Curiosity”, or “Usefulness to others”)… you can see this list of common values in ACT, if all this parlance of values remains too abstract. Finally, and this is critical, rate how important each area is for you right now (in a 1-10 scale), and how much your actual behavior in an area is matching these values, lately (again, in a 1-10 scale). By looking at those two numbers, we can see which areas might be causing us trouble these days: what are the areas that have high importance, but low behavior alignment? We may want to focus on those areas first, when doing the rest of this yearly review.

3. Look to the future

Now it’s time to connect these lofty high-level values we care about, to actual actions during this coming year. I like to do this through a top-bottom approach. Taking a page from Cal Newport, I have recently tried doing a “lifelong strategy document”: this is a short document (or documents – you could have, e.g., one for your personal life and another one for your professional life), in which we lay out in brief what is our current best guess for how to manifest the values we unearthed in Step #2 above, into actual long-term (and maybe shorter-term) goals, into particular projects and habits. These do not need to be very long (my two documents are around 1000 words each), or elegantly written: the goal is to have a summary of our core ideas for what direction we want to go with our life in the next years. Also, we shouldn’t be afraid to get things wrong (spoiler alert: we will): these documents can be tweaked, rewritten, fine-tuned in our periodic reviews (e.g., quarterly or, as we see here, yearly). We will learn more about what works and doesn’t work in our lives as we go.

The way I structure these documents generally goes like this: every document is divided into several parts, one for each area (or group of areas, see Step #2) of my life. ACT guidelines suggest that we focus first on areas of our life that are high-importance, but low in behavior manifestation (see the scoring of areas at the end of Step #2), as those are more likely to be the ones causing us suffering4. For each area, I list again the main value keywords distilled in Step #2, and try to think what long-term strategy or projects I have for manifesting those in my life: where do I want to be in 5, or 10, or 20 years, if I follow these values? Then, slowly try to work back from those visions, to something I can do in the short term (e.g., a project I can complete this year). Other things I mention in this document are important day-to-day habits that embody those values, that signal to myself that I care about this area of my life (what Cal Newport calls ‘keystone habits’). Something tractable, but not trivial I can do every day to embody this direction I want to take in this area of my life.

To give an example, here is a schema for one of these areas (the part of my professional strategy related to this blog) in my “professional lifelong strategy” document6:

Area: Professional career + citizenship + learning

Core values: Independence/Freedom, Creativity, Usefulness (to others), Collaboration, Curiosity

Long-term strategy: Try to solve the wellbeing and productivity problems of doctoral education, through writing in the blog and giving associated talks, seminars or workshops on the same topics. This will allow me to help others, do something creative, learn how to supervise doctoral students better myself (and eventually make enough money to sustain the time spent and the whole initiative?).

Shorter term projects, for this year: Keep the initiative alive, in the new personal circumstances (less free time to research/write in the blog): try different types of posts that take less time to prepare. Find out the costs and pricing of seminars/courses I could deliver. Try different income channels.

Key habit: Write blog entries, without distractions, for at least 25 minutes (one pomodoro) each day (preferably, first thing in the morning).

As we can see, the long-term strategy will still be quite vague and grandiose, but that is OK (it is something to be achieved in multiple years, maybe a lifetime). The key is to then find something we can work on in the shorter term, as stepping stones to that lofty goal.

If we are currently embarked in doing a doctoral dissertation, probably our thesis work will be mentioned somewhere in these documents: we can define there our most immediate milestone or milestones for this year. Not the thousand things we need to do related to our thesis, but what are the key necessary elements, the things we would still do even if we could only spend 20% of the time we think we have on it. And we can define shorter-term projects and habits that we think would act as fuel to move us towards that milestone. Thus, we will have connected abstract values that are very important for us (like autonomy, connection or self-improvement), with very concrete milestones, projects and habits to help us finish our thesis. In my own experience (and according to therapy approaches like ACT), this connection helps in being more consistent in our efforts (i.e., do the stuff that is needed, even on days when we “don’t feel like it”) and in being resilient against setbacks.

As a final step in this future-facing part of the yearly review, I then look at my calendar for the coming year, and write down the big events of the year: what are the big conference or journal deadlines you need to work towards? what important projects or studies will occupy long stretches of your time? Is there a defense in the horizon this year? some other personal big dates that you want to prepare for in advances, like weddings or anniversaries? Make sure to have them clearly marked in your calendar. (Pro tip: for big important deadlines or project deliverables, you can also put in your calendar “kick-off” or “midway” marks as checkpoints to remind yourself to scope or monitor your advances towards these “big stones”). Finally, you can already book in advance in your calendar, in a recurring way, time for activities that you want to do more of, as per your retrospective analysis of “good things” from last year (see Step #1). For instance, I have made a recurring daily event in the morning to sit down and write for the blog (see the blog-related strategy example above), and a weekly one to visit a local farmer’s market (something I enjoyed a lot during 2021).

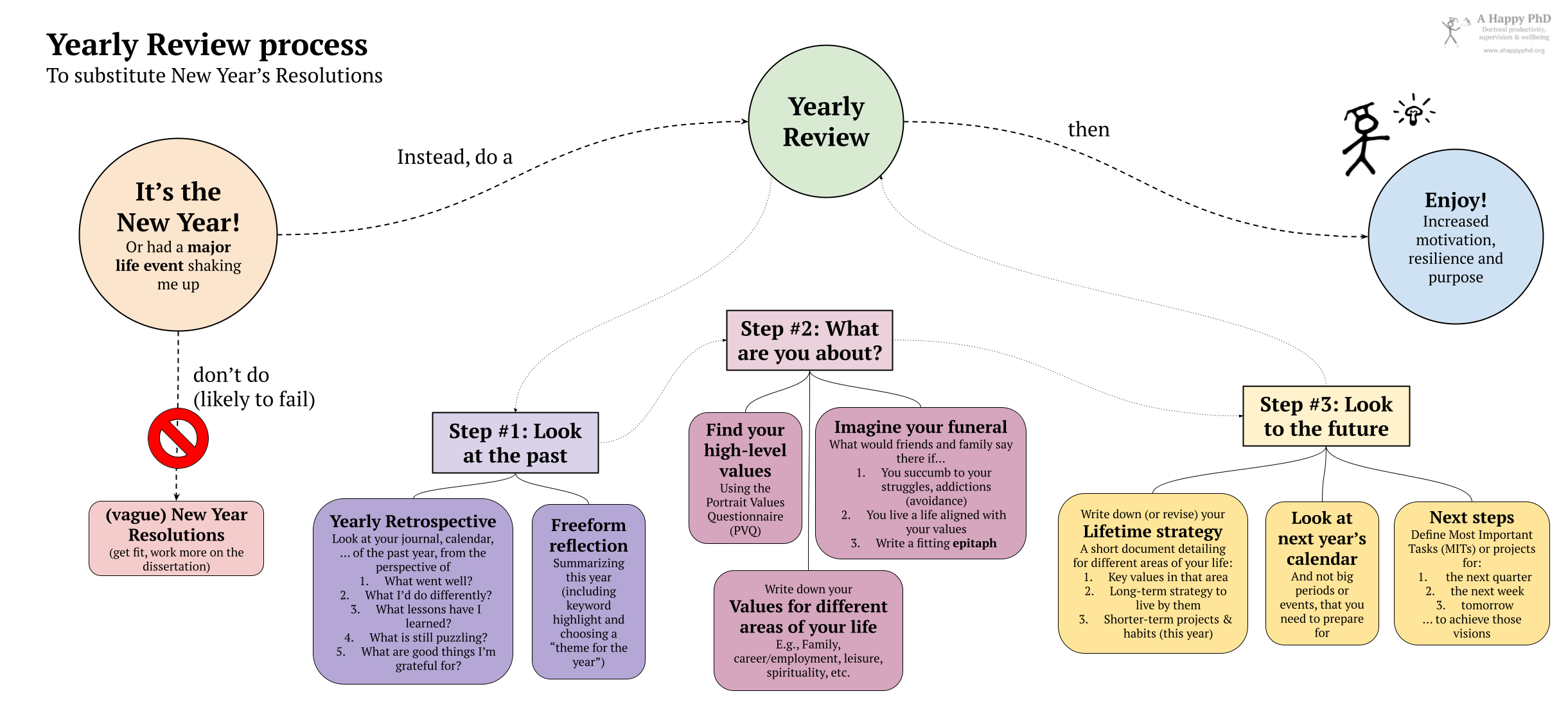

As we can see, this last part is somehow similar to the old “New Year’s Resolutions”, but here we get much more granular in terms of different levels of action, and pay special attention to connecting these changed behaviors and new projects with qualities important for us, with the why behind them. The diagram below summarizes the whole Yearly Review process I just described:

Next steps and over to you

Having an analysis of the past year, of my values and of the next year’s big strategies, I then do the future-oriented part of the reviews for the next period, at shorter and shorter horizons: I set 1-3 main projects/goals for the next quarter of the year (i.e., three months) and what habits and strategies will help me achieve them; I set 1-3 most important tasks (MITs) for the next week (see the future-facing part of my weekly reviews), which put me on the path to achieving the quarterly goals; and I set the MITs and to-do shortlist or calendar configuration for the very next day. By now, I’m really eager to tackle those, because I know where those first baby steps are leading me to! :)

At almost 4,000 words of description, I’m aware that this process sounds long and complicated. Yet, I find every minute of this process worthy: I have noticed an increase in motivation and a greater sense of coherence and purpose in my life, since I first did this process. Having such high-level beacons in different areas of my life has provided me with resilience in the face of setbacks: when a plan or a goal doesn’t work as expected on the third day of trying, I now can look for alternatives that are still aligned with my values, rather than throwing up my hands in the air and giving up all hope. Along with a dose of mindfulness and gratitude practice (and the writing of this blog), I credit these reflections and planning with making my low-grade depression go away.

Try it, and let us know how it worked, in the comments section below!

Header image by Marco Verch via ccnull.de.

-

Dai, H., Milkman, K. L., & Riis, J. (2014). The fresh start effect: Temporal landmarks motivate aspirational behavior. Management Science, 60(10), 2563–2582. ↩︎

-

Norcross, J. C., & Vangarelli, D. J. (1988). The resolution solution: Longitudinal examination of New Year’s change attempts. Journal of Substance Abuse, 1(2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(88)80016-6 ↩︎

-

Dickson, J. M., Moberly, N. J., Preece, D., Dodd, A., & Huntley, C. D. (2021). Self-Regulatory Goal Motivational Processes in Sustained New Year Resolution Pursuit and Mental Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063084 ↩︎

-

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. ↩︎

-

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., & Owens, V. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 519–542. ↩︎

-

NB: The real strategy document is a bit longer than this, and is written as (slightly rambling) prose paragraphs. Here I have summarized the main ideas for a quicker read. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.