POSTS

How to restart our PhD habit after a productivity slump

by Luis P. Prieto, - 15 minutes read - 3057 wordsA family member dies, or their health fails catastrophically, requiring intense caregiving. A workload spike at our thesis-unrelated job becomes an ongoing plateau. Life’s logistics somehow magically align to get in the way, again and again. The experience of a “hair on fire” emergency morphing into a prolonged thesis progress slump is more common than we think. My recent hiatus from blogging has helped me see this common problem of doctoral students in a new light (and to experience it firsthand). This post explores mindsets and strategies that can help us return to making regular progress on our non-urgent but important projects (a.k.a. the thesis).

You may have noticed the blog’s inactivity in late 2024 (almost six months, indeed!). This wasn’t due to any strategic planning, but rather because various obligations – both work-related and personal – unexpectedly took over my schedule and pushed me into what I call “emergency mode”: a state of constant hurried activity just to keep one’s head above water, where carefully crafted productivity and self-care habits crumble. Our long-term important projects, like thesis work, inevitably get neglected in emergency mode.

This recent episode, which derailed a project important to me, has made me even more empathetic toward PhD students who find themselves in a “thesis progress slump” lasting weeks or months (a phenomenon I’ve witnessed repeatedly in my research career). While this is especially common among part-time doctoral students and those with significant non-thesis obligations (children, jobs to pay the bills, etc.), really anyone can fall into this pattern.

In this post, I’ll examine the two main mechanisms I believe explain most PhD students’ (and my own) productivity slumps, then draw from scientific literature, self-help/productivity advice, and personal experience to offer strategies and mindsets for breaking out of the slump.

Two intertwined causes

The immediate cause for a “thesis productivity slump” is probably obvious for the person suffering it: a deadline crunch, an unexpected family-related event or obligation… In my case, a research project management milestone I had failed to plan for, paired with start-of-school viruses mangling our childcare plans, plus teaching obligations I was not used to. This kind of immediate first cause(s) suggests that task conflict is behind the problem. Task conflict, i.e., multiple tasks and projects that are important for us (or have important consequences if not done) interfering with each other, is one of the most common PhD productivity challenges. How does such conflict work? Basically, the other (usually, urgent) obligations create a feeling of time scarcity, which is well-known1 to create a narrowing of attention (i.e., we do not consider the long-term thesis tasks as important, or we simply forget about them altogether). Put simply, the urgent task gets done even if its importance is lower than the long-term non-urgent project. PhD students are especially prone to this tunnelling phenomenon, as they often face non-thesis obligations that can be quite urgent (e.g., teaching, lab projects, or family obligations)2.

Yet, once the obvious task conflict has derailed our “thesis habit”, a second, more insidious mechanism kicks in, helping the productivity dip become a slump (or a yawning Great Canyon): procrastination. Defined as “voluntarily delay[ing] an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay” 3, procrastination is another one of the most typical PhD productivity challenges. Procrastination can be triggered by several factors: we dislike or fear the postponed project (task aversiveness), we feel like we will not be able to succeed at it (low self-efficacy), we give priority to short-term rewards – e.g., helping students we are teaching to – over long-term ones – e.g., finishing the thesis – (temporal discounting). Procrastination also appears more often for people that tend to be impulsive or distractable, or who have poor time management and organization skills3. We can see how easy it is for a PhD student (even a non-impulsive one) to trigger these procrastination mechanisms, since PhD work is often hard (cf. aversiveness), and as novice researchers we are still learning to do it (cf. self-efficacy).

Depending on each person’s particular case, a third (and further) causes can be layered with the aforementioned two: a variety of emotional well-being symptoms (e.g., those for stress, anxiety, depression) can further cloud our judgement and widen our slump – especially if we are a bit prone to any of them. This is probably why mental health issues are the third most common PhD productivity challenge.

Getting out of the slump, one step at a time

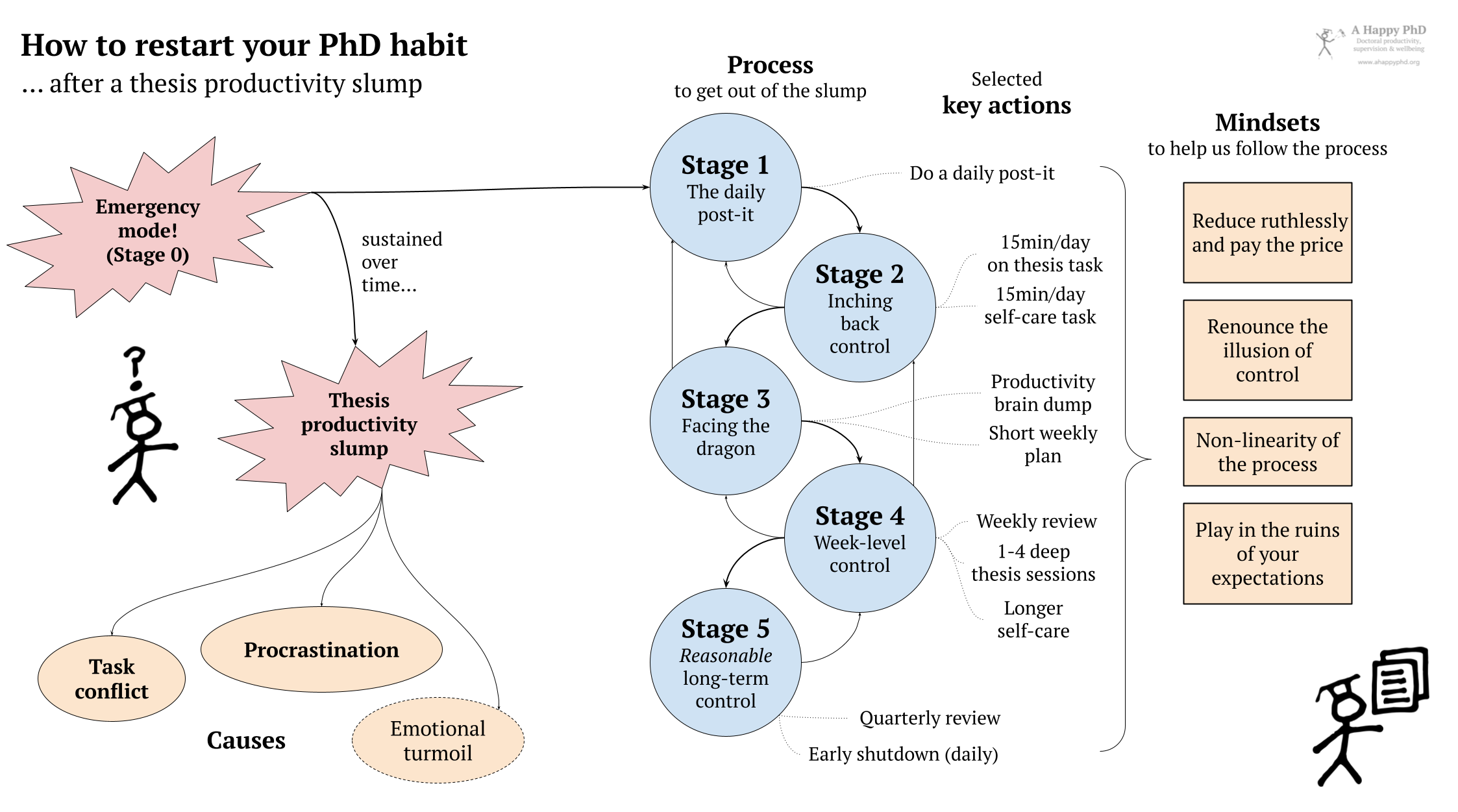

Similarly to what we did when addressing to-do list overwhelm, I’ll lay out a rough multi-stage process to crawl out of the thesis productivity slump. This approach draws from my experience, as well as common advice in psychology, organization, and self-help literature. The key idea is to progressively transition from chronic overwhelm – where we feel no control over our life and see no progress in long-term important projects – to a state of being “reasonably on top of things” and making regular progress on non-urgent projects like the thesis.

Stage 0 (a.k.a. Emergency mode). This is where most thesis and long-term project slumps begin. We’re stressed, continuously overwhelmed, running around putting out fires, with an ominous feeling we’re forgetting important things (but no time to stop and think). This state often comes with despair that it will last forever, or anxiety that it’s just the prelude to worse catastrophes (losing our job, being ostracized, our children falling sick) caused by our negligence. Usually, we’ve abandoned all our productivity and self-care routines, feeling too much in a hurry to spare time for that.

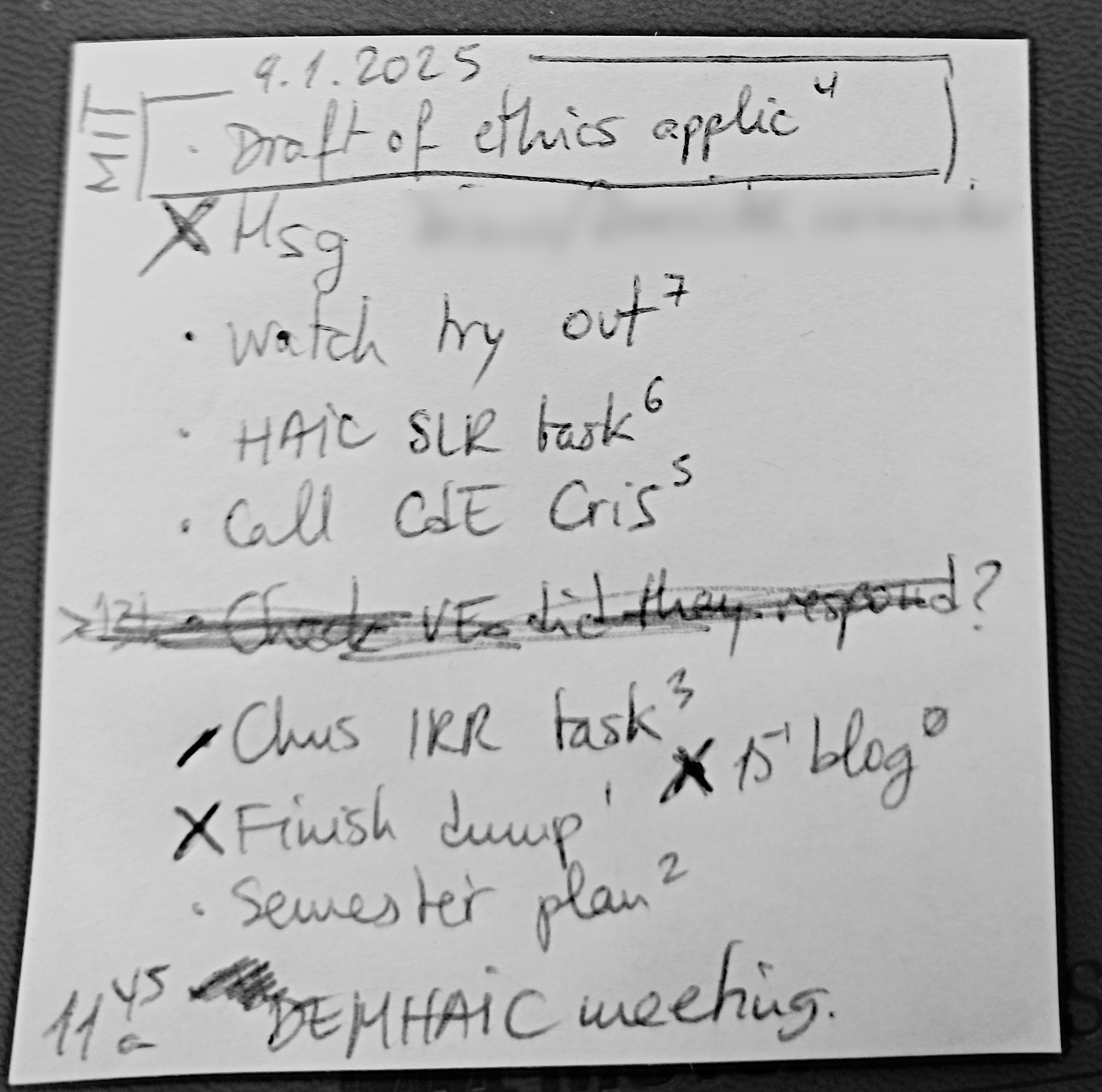

Stage 1: The daily post-it. At this stage, we still experience the same time scarcity and stress, the same feelings of impending doom… but we’ve managed to pause for a few minutes to take one key action: breathe deeply once or twice, and list on a post-it or similar piece of paper the tasks and appointments just for today (this could be a digital note on the phone, but I find paper helps me focus4). Then, we execute that minimalistic plan. Finally, at day’s end, we create the same kind of post-it for tomorrow. Bonus points if we designate a Most Important Task (MIT) for the day – one we’ll prioritize and surely finish (as completing it provides a sense of efficacy and agency). Planning the order of tasks can also help. See the picture below for a recent example of mine. This level of productivity might seem pathetic, but it differs qualitatively from “hair on fire emergency” mode – it raises our “expectancy of success” by making tasks smaller, which helps with procrastination3 and puts us more in control, laying important groundwork for Stage 2.

Stage 2: Inching back control. After a few days of being consistently in Stage 1, we’re still generally stressed, but may feel slightly more hopeful, like we could actually do something about what’s long-term important for us. Now it’s time to up the ante with two key actions. First, add to the daily post-it (see Stage 1) one seemingly small but important task: set aside 15 minutes to work on a thesis task. Time this and remove all distractions to curb procrastination3, as in the Pomodoro technique. If possible, choose something core to the current thesis phase rather than a menial task – ideally something that advances us toward our next thesis milestone (yes, creating or reviewing a thesis map around this stage will help us prioritize2). Then, just do it (preferably, first thing in the workday, before email or other tasks). One often finds it hard to stop when the bell rings – one actually wants to continue doing it (thus overcoming the task aversion aspect of procrastination). Stop or continue, doesn’t matter; what matters is that we’ve now made progress toward our thesis goal. And celebrate it!

Equally important: add another 15-minute self-care “task” to the post-it. Choose whatever is particularly suitable, challenging but doable. My favorites are: 1) a simple yoga-mobility-stability routine focusing on the shoulders (a weak point since my tendinitis); and 2) a 10-15 minute non-sleep deep rest (NSDR) (something between a nap and meditation) after lunch. Both options improve my physical and mental state for facing a stressful day, but they’re just examples. The key thing about this stage’s two actions is that they create productive routines3, showing ourselves that even when stressed or busy, we have time for non-urgent but important things (health and thesis).

Stage 3: Facing the dragon. After about a week of consistent Stage 2 practice (writing the post-it and making time for short thesis and self-care tasks), we probably feel better but can’t avoid realizing that a PhD thesis won’t be finished in 15-minute increments. This is the turning point. The key action is making time for a one-time 1-2 hour slot to take stock – what I call the “productivity brain dump”: list all current and pending projects and activities on paper. Divide them into professional (thesis and other jobs/roles) and personal projects (caretaking, life admin, and anything else occupying mind and time). Include nagging one-off tasks too. Keep the paper handy to add things as they come to mind. The goal is getting everything stressful out of your head and onto paper – then facing it.

The result will be scary (hence, the dragon metaphor). My most recent dump had thirty distinct threads/projects, each made of its own sequence of tasks. Now comes the hardest but most necessary part: accepting we can’t do everything at our desired quality level (or at all). Time to strategize: step out of as many threads as possible. Be honest (but not a jerk) about it – explain we can’t do them now, perhaps deferring until a clear future workload dip. Then highlight especially important threads (those with real consequences or directly connected to a thesis milestone). As a corollary, do a short weekly plan for the week ahead (revise important upcoming tasks/appointments, define 1-3 MITs for the week, set a habit/mantra – see our weekly review protocol), that already takes into account this new picture of our (hopefully curbed) obligations. In this plan, we need to make sure that we a) sleep enough (as the base for our cognitive, emotional and physical state); and b) have at least one longer exercise session. Time-blocking or our old “calendar trick” for task management can be helpful to execute this plan.

Stage 4: Week-level control. If we managed Stage 3 successfully (including paring down obligations), we’ve likely earned some head room to think strategically, even if daily life remains intense. The goal now is to make the stage 3 actions a habit – automaticity and routine are key levers against procrastination3. Keep the daily post-it and short thesis/self-care actions, but now add 30-60 quiet minutes at week’s end for a full weekly review. Reflect on the week (using daily post-its, calendar, and/or journaling to aid our faulty memory), then plan the next week. During the review, we revise our “productivity brain dump” for important items to add. Keep checking for projects to drop – either because they’re not crucial or because progress is unlikely soon. I’ll repeat it: we need to drop, drop, drop as much as we can.

The key action here is adding progressively more “deep thesis sessions” to our weekly plans – 60-90 minute blocks tackling hard thesis tasks that lead to our next milestone 5. Start with one session and build up to four per week. Also schedule longer exercise and self-care sessions (30+ minutes, once or twice weekly). Protect these calendar slots like any other appointment – this is where real progress happens! Another tip: for those of us that struggle to reduce commitments due to social pressure (i.e., disappointing others is very uncomfortable), we can use that trait strategically in our favor by establishing social accountability3: setting thesis deadlines or self-care appointments with people we’ll hate to disappoint and who’ll call us out on our avoiding them.

Stage 5: Reasonable long-term control. Many people never reach Stage 4 stably. But if we do, we can add two key actions that seem small but significantly reshape our mental landscape. First, implement a quarterly/semester review: a 2-3 hour session, similar to our yearly review, at the start of each relevant period (I do one per teaching semester plus summer). In it, we look back to learn what works, reflect briefly on our values, and plan ahead – projects, dates, time management (including dropping again unrealistic activities). Second: adopt the habit of doing an early shutdown at workday’s end. Review today’s to-dos, check what remains in the weekly plan, and realistically face tomorrow’s possibilities as we write that daily post-it. This keeps personal time and nights freer from rumination, helping us stay present in our personal life. A daily journaling practice is optional but recommended – a 5-minute action with outsized impact on my psychological outlook.

That’s it.

Useful mindsets for breaking out of the slump

The process above may look simple on paper but often proves terribly difficult to implement amid real life’s unexpected occurrences (that’s why we fell into the slump in the first place!). In my experience, what you do may matter less than how you approach this process – the attitudes and mindsets that make the process bearable (and even enjoyable!). Here are several I’m finding helpful while breaking out of my own slump, each worthy of a “monday mantra” card:

-

Reduce ruthlessly… and pay the price: Restarting thesis productivity always comes with a price tag (as mathematicians say, there’s no free lunch). When we’re overcommitted or life becomes complicated, we can’t simply start dedicating substantial time to the thesis. We must ruthlessly reduce our projects or lower the quality of our outputs. We will have to tell people we can’t meet certain commitments, perhaps be less of an ideal parent, coworker, sibling, or friend than we’d like (at least temporarily). Shame and other negative feelings will arise. Don’t be a jerk while reducing, but if this serves a long-term goal aligned with our values, we can try to befriend (or accept) these feelings and move forward, knowing the price is worth it.

-

Renounce the illusion of control (a.k.a., befriend your uncertainty). Notice there’s no Stage 6 (full control). We’d love to feel perpetually “on top of things”… but that’s an illusion. Like surfing, you can only ride the wave so long before it crashes. Something will always throw us off balance. Some weeks will feel more controlled than others – and that’s OK. Achieving long stretches in Stage 5 is plenty good. Uncertainty (about meeting deadlines, being good enough parents) is inherent to research and all meaningful human activity. One technique I find useful for befriending uncertainty and other uncomfortable feelings that have come lately is the “three minute breathing space”, a simple mindfulness technique similar to our classic “sitting with uncertainty” exercise for scientific writing.

-

Acknowledge the nonlinearity of the process. The description of stages above might suggest a clean progression (0-1-2-3-4-5). I can almost guarantee that won’t happen. New deadlines or setbacks will emerge, pushing us into less controlled states. My own path has been more like 0-1-2-0-2-3-1-2-3-4… and even while approaching Stage 5, this morning I still needed a daily post-it (Stage 1) because my planning routines had slipped over the weekend. And that’s fine.

-

Play in the ruins of your expectations. This process involves substantial planning: daily, weekly, semester plans… repeated continuously. Planning inherently creates expectations about how time will unfold. When these expectations break (incomplete daily to-dos, missed semester MITs), we feel inadequate, ready to abandon the thesis. Yet there’s no reason to believe that our quickly-jotted list of planned tasks represented our actual capacity. Our plans are usually impossible, failing to account for interruptions, planning fallacy, etc. I love this idea of “playing in the ruins” (by Sasha Chapin, via Oliver Burkeman6): acknowledge the fantasy of planning, the reality of today as it is (not as we planned), and playfully discover what we can do with the remaining scraps that still move us forward in life and in the thesis. Perfect adherence isn’t the goal – remaining intentional about what we do with our time is. The concept that “to-do lists are menus” (another Burkeman classic) applies equally here: we can’t taste everything, just thoughtfully select and savor our next value-driven task.

The diagram below summarizes the main ideas of this post:

Over to you

For a blog restart, this piece has grown quite long. My own productivity slump isn’t fully resolved – I’m still navigating between Stages 3 and 5 daily. Indeed, this post serves as much as self-guidance as it is advice for others.

But do try it out and share whether it helped with your own slumps.

I really hope it does.

The comments and voice message sections remain active, and I read/listen to all (though responding had to go during my own Stage 3, to enable this comeback you are reading).

Header image by Midjourney. Claude and ChatGPT were used to mine for research strands that could help explain productivity slumps. NotebookLM was used to pinpoint relevant passages characterizing causes and solutions to the slump, from the actual academic papers on the topic. Claude was used to remove grammatical mistakes and streamline the prose slightly – if this post looks long, imagine how much more rambling was the original version! ;)

-

Shah, A. K., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science, 338(6107), 682–685. ↩︎

-

van Tienoven, T. P., Glorieux, A., Minnen, J., & Spruyt, B. (2024). Caught between academic calling and academic pressure? Working time characteristics, time pressure and time sovereignty predict PhD students’ research engagement. Higher Education, 87(6), 1885–1904. ↩︎

-

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65 ↩︎

-

da Silva, L. A., & Ramos, A. S. M. (2023). Understanding the Distraction and Distraction Mitigation Factors and Their Relationship with the Procrastination of Master’s and Doctoral Students in Administration. Journal of Education and Learning, 12(4), 50-61. ↩︎

-

Perlow, L. A. (1999). The time famine: Toward a sociology of work time. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 57-81. ↩︎

-

Burkeman, O. (2024). Meditations for mortals. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.