POSTS

Impostors and supervisors - Personal and contextual factors in a happy PhD (study brief)

by Luis P. Prieto, - 8 minutes read - 1639 wordsIn the blog we have written a lot about doctoral well-being, from different angles… but what personal and contextual factors seem to affect it? A recent study out of Italy asked 216 students about this and about challenges to their well-being. In this post, we summarize the study and its findings, connecting these results with prior ideas in the blog, and how we can apply them in our own doctorate journey to find better well-being.

As part of my efforts to fight creeping burnout (including burnout about the blog) in 2025, I’m trying to inject back some of the old evidence-based emphasis and learning motivation that I had when I first started the blog. In this new kind of post (the ‘study brief’)1, I try to summarize recent research studies in doctoral education (on key topics of the blog, like doctoral well-being, dropout, productivity and supervision), their findings, and what they mean for us. All in an effort to keep myself (and you dear readers) up to date and learning about what researchers have found about what works in doing (and/or supervising) a PhD.

Without further ado, let’s get on with today’s study brief:

The paper: Petruzziello et al.’s (2024) "‘Is it me or … ?’. A multimethod study to explore the impact of personal and contextual factors on PhD students’ well-being”2

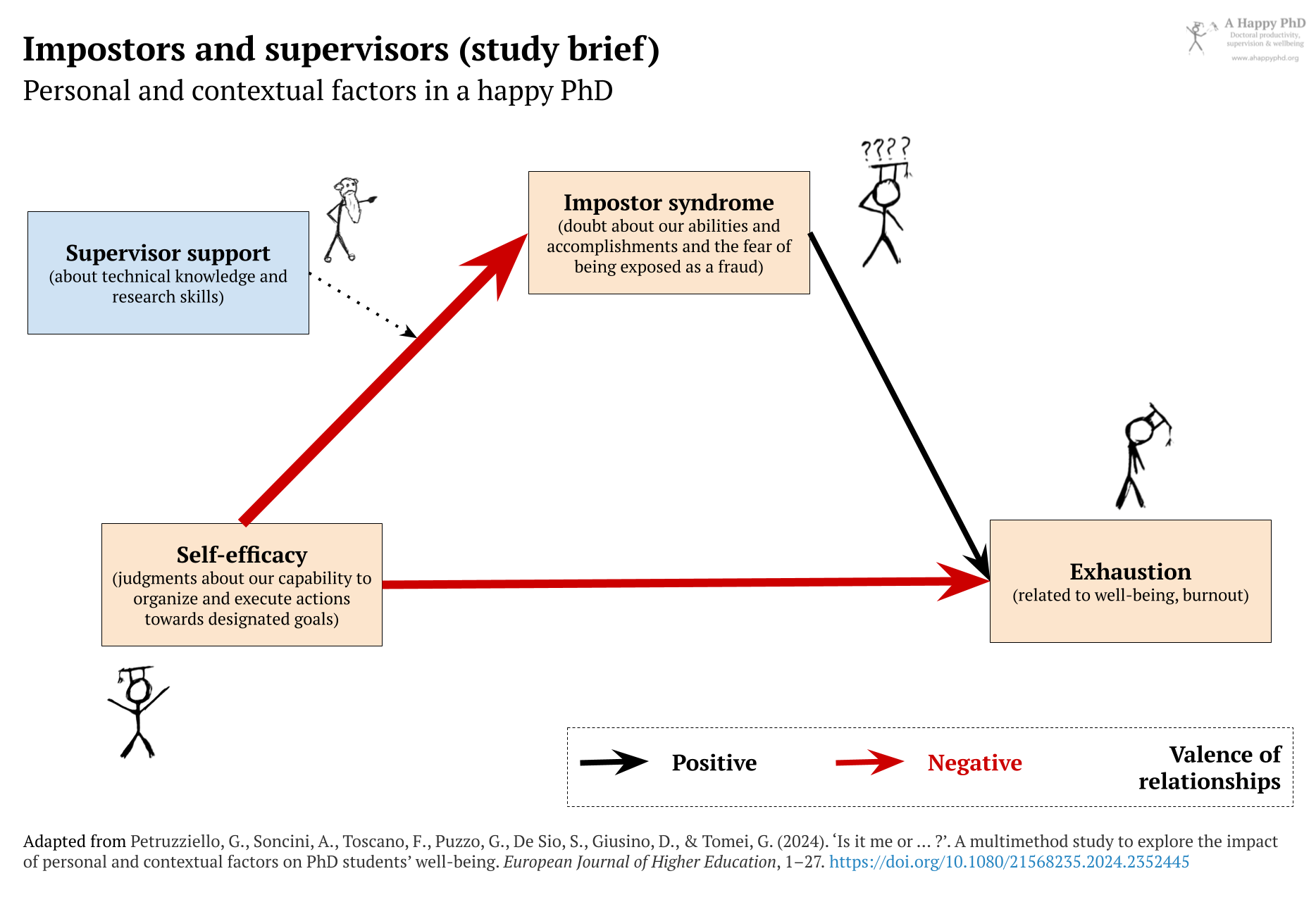

What they did: They passed a questionnaire with open and closed questions to N=216 doctoral students in an Italian university. The questionnaire measured things like emotional exhaustion (one key component of burnout), self-efficacy (our judgments about our capability to organize and execute actions towards designated goals), how much supervisor instrumental support (e.g., about technical knowledge and research skills) they perceived, and how much impostor syndrome they felt (i.e., the doubt about our abilities and accomplishments and the fear of being exposed as a fraud). It also asked for the main challenges doctoral students faced during their PhD. Then they did a quantitative analysis of the former, and a qualitative analysis of the latter (to group/classify the challenges reported).

What they found: The main quantitative results suggest a model that can be summarized in the figure below: feeling like you are capable (self-efficacy) is negatively related to exhaustion, and it is also negatively related to impostor syndrome (you feel less like a fraud). And, the more you feel like a fraud, the more exhausted you are likely to be. So far, pretty obvious: the more resources you feel you have (another way of seeing self-efficacy), the less exhausted you will be – and impostor syndrome is an important mediator in this relationship.

More interesting (and tricky) is the role of the supervisor here: while researchers anticipated that more supervisor support would lead to lower impostor syndrome (and hence, less exhaustion), the relationship they found was more nuanced: “PhD students with low levels of [self-efficacy] reported higher perceptions of [impostor syndrome] when perceiving high supervisor support than low supervisor support.” In other words, if you already feel not-capable, you will probably interpret the supervisor support as further proof that you are indeed an impostor (!). On the bright(-ish) side, the effect of such supervisor support is relatively small compared with the other relations in the model.

Regarding the challenges of these Italian PhD students, what researchers found not very surprising if you have been reading our blog (or attending our doctoral workshops in Estonia and Spain): there are contextual challenges (about organizational culture, relations with supervisors and colleagues, and demanding job aspects like task conflict) and personal challenges (lack of motivation, fears and doubts relatable to impostor syndrome, or psychological distress symptoms like anxiety or depression).

Why this matters: Impostor syndrome has long been an “underground classic” of the doctoral process: people that are doing or have finished a PhD see the syndrome as very typical of the doctoral process (see this classic PhD comic), but people coming into a PhD (or the general public) do not expect this relationship. This study further cements this intuition we had about impostor syndrome, and identified a potential, more general, upstream cause (self-efficacy), which we could target through training and interventions. It also provides a (mild) warning to supervisors, to consider the support they provide a bit more carefully.

Connection to the blog’s ideas: Several ideas in the study supported research and advice we have reported about in the blog. Impostor syndrome and self-efficacy featured heavily in our post about using self-determination theory to avoid dropping out of the PhD, and the notion that doctoral supervision needs to adapt to the student needs and profile has also been discussed here (one of the “PhD student profiles” defined in that post is clearly related to the low self-efficacy students in the Italian study). The qualitative side of the study also resonated deeply with our classification of the top doctoral productivity challenges, including demanding aspects of the students’ job(s) – especially what we call task conflict (having multiple projects or obligations, which often hampers progress in the thesis).

How to apply this in real PhD life3: Now that we know about these relationships between (rather abstract) constructs like self-efficacy, impostor syndrome, and exhaustion… what can we do about it in practical terms? As doctoral students, the obvious strategy is to improve our self-efficacy, as the more general upstream factor. According to Bandura4, there’s four sources that go into this belief in our capabilities: enactive mastery experience (succeeding at the task ourselves), vicarious experience (seeing others succeed), verbal persuasion (others telling us we can do it) and physiological or affective states (how we deal with the stress and uncertainty of the task and/or failing at it). Typically, this involves progressive mastery in your research tasks, for instance by having clear structure/expectations to the tasks of your PhD (don’t be afraid to ask about concrete expected output of any non-trivial task in your PhD, be it a report, a data analysis, etc.). Exposing and discussing your ideas about your thesis topic (e.g., through CQOCE diagrams) with colleagues and supervisors, and having some curiosity-based explorations of ideas or literature around your PhD topic (to slowly develop your identity as “the expert” on it) will also help. Getting training about research skills you feel an impostor about can also support your self-efficacy, especially if they have a practical component that you can tie directly to your thesis topic and research tasks. You can also try other practice-oriented placements that develop specific skills you will need (e.g., lab rotations in more lab-oriented disciplines; or “shut up and write” groups for research writing). Another one I’ve seen work many times is peripheral participation on papers or projects of your team/supervisor, which provides both progressive mastery and vicarious experiences, helping you see “how the sausage is made” and normalizing the setbacks and failures that even more experienced researchers face. If you are lucky enough to have that sort of thing around you, mentoring and coaching (including peer mentoring) programs can also help with the verbal persuasion lever of self-efficacy. Finally, multi-week, multi-component trainings targeting both mental health skills and more practical/productivity skills (especially if they specifically try to connect with your everyday research practice, as our “A Happy PhD” workshops try to do) can help with the physiological/affective as well as the other sources of self-efficacy5.

On the other hand, for those of us that are doctoral supervisors, the key insight is to train yourself about these issues and about supervision in general (that’s why we also have “A Happy PhD” workshops for supervisors). More generally, this study also prompts us supervisors to avoid “blanket supervision practices” applied to every student – rather, observing and discussing with the student what level of support is needed for them to progressively master the research and transversal skills they need to master.

Probably this is enough for what was supposed to be a study brief :)

Is this new kind of post useful? Are you interested in reading about the latest developments in doctoral education? Let us know in the comments below, or write us an email. We do not answer every email, but we do read all of them!

Header image by OpenAI’s DALL-E6

-

This idea came from the excellent “Import AI” newsletter about advances in artificial intelligence (AI), which summarizes pretty technical papers in a very accessible manner. Kudos to Jack Clark for doing that! ↩︎

-

Petruzziello, G., Soncini, A., Toscano, F., Puzzo, G., De Sio, S., Giusino, D., & Tomei, G. (2024). ‘Is it me or … ?’. A multimethod study to explore the impact of personal and contextual factors on PhD students’ well-being. European Journal of Higher Education, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2024.2352445 ↩︎

-

This bit has been written based on my own experience and the outputs of a quick literature search done with OpenAI’s DeepResearch. See the full conversation here for further details and references. ↩︎

-

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 ↩︎

-

Gueroni, L. P. B., Pompeo, D. A., Eid, L. P., Ferreira Júnior, M. A., Sequeira, C. A. D. C., & Lourenção, L. G. (2024). Interventions for Strengthening General Self-Efficacy Beliefs in College Students: An Integrative Review. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 77(1), e20230192. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2023-0192 ↩︎

-

The prompt used was “A photorealistic image representing the theme ‘Impostors and Supervisors: Personal and Contextual Factors in a Happy PhD.’ The image features a split composition: on the left, a PhD student sitting at a desk, facing right, looking anxious and overwhelmed, with imposter syndrome imagery such as shadowy figures whispering behind them. On the right, a supportive supervisor sitting across, facing left, engaging in discussion, providing guidance with a reassuring smile. The background shows an academic setting with books, a laptop, and research papers. The lighting contrasts between the left (dim, uncertain) and the right (warm, encouraging).". ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.