POSTS

Cultivating the progress loop in your PhD

by Luis P. Prieto, - 17 minutes read - 3607 wordsHave you ever felt like you are “stuck” in your PhD, making no progress, or going in circles? If so, you are in good company – most PhD students report such experience at one time or another during their doctoral process. The normalcy of this experience, however, should not make us dismiss it as unimportant. In this post I review research that speaks to the importance of this sense of progress (or the lack of it) to our engagement with work and the eventual completion (or dropping out) of the PhD. The post also reviews several everyday practices to cultivate your own sense of progress.

But, first, a warning: don’t be mistaken, feeling like your work is stagnating, that you are swamped in your progress, is not something that goes away once you get a PhD. Only a few years ago, well into my postdoc phase, I remember my despair after a long series of workshops and collaborations had lead to precisely zero results: the data gathered was not of enough quality, participants and collaborators were too busy to continue working with us, so the research idea I had been pouring so many hours onto, just faded away without any tangible result. My motivation was at an all-time low, and I was tempted to just lock myself in the office and do… nothing. What was the point? I thought.

It took me quite a while to pull myself out of that hole, and I was surprised by how persistent and acute the feeling of demotivation and helplessness was, even if I knew rationally that such setbacks happen all the time in research. Only recently, I’ve read books and studies that have helped me make sense of that process I was going through.

The power of small wins

In The Progress Principle1, Amabile and Kramer describe a diary study they did with 238 employees of seven creative/innovation companies of different sectors. During several months, employees filled in a diary entry about an important event that day at work, along with questions about their mood, productivity, and many other variables (including also assessments of their productivity by their colleagues and bosses).

Analyzing more than 10,000 of those diary entries, the authors noticed several patterns. Maybe the most important one was about the main distinguishing factor or event that appeared in a journal entry in a “good day at work” (as opposed to “bad days”): it was the fact of having made progress in their current projects or tasks, regardless of whether the progress was a big event (e.g., getting a million-dollar contract with a new client) or a small one (e.g., a programmer solving a small software bug that had been elusive for several days). Conversely, having a setback event, any event that signaled that their project was “stuck” or “going in circles” (e.g., the boss redefining the project’s goals, thus forcing the team to re-do the work of the last weeks) was a common marker of a bad day at work.

The authors are also quick to note that it is progress in work that matters (meaning, it matters to the person doing it)2. This does not necessarily mean that you are finding a cure for cancer, but it requires that the work is creative, challenging, that we feel it as our own (i.e., ownership), and that we feel it is consequential (i.e., that it will benefit us or others, be it because it will help us learn a new skill, or because other people will use its outputs).

This importance of feeling that one is making progress on meaningful work also manifests in what the authors call the progress loop: making good progress in a meaningful project generated good emotions (which is a reason people consider a day good); in turn, these positive emotions and perceptions of the work and the team made people more creative and more productive in the following days; and, of course, when people are more productive, they tend to make even more progress. Successful teams and workers were able to sustain this virtuous cycle for longer periods of time.

OK, you might say, this is all very interesting, but this was a study on the industry, with employees of US companies, a very different environment to mine. I am a PhD student in academia in a different country. Why should this apply to me as well?

Progress matters… between PhD persistence and dropout

Well, for one, I would say that a PhD has a lot of potential to be “work that matters”: it is creative, challenging, it is helping you acquire new skills (i.e., it is consequential for you, at least)… and hopefully you feel that your dissertation is your own project. Nevertheless, the question of transferability of Amabile and Kramer’s results is a real one, which made me think: might there be some similar research done in doctoral education?

It turns out there is.

The research in question is a much smaller study3, in which 21 ex-doctoral students in Belgium (13 of which had dropped out, and 8 who had completed the PhD) were interviewed about their experience during the doctoral process. Among other things, the interviewees were asked to describe what a good day or a bad day in the PhD was like.

The qualitative analysis of the interviews noted that some of the usual factors that come to mind as important (e.g., PhD advising quality, or peer/colleague support) did appear a lot in the interviews. However, these factors were not appearing differently between participants that had completed the PhD and those that had dropped out. In some cases, doctoral students who had very supportive supervisors still dropped out for other reasons – and vice-versa (e.g., there were people that had bad peer support or lab ambience, but still were able to complete the PhD).

What the authors found was differential between PhD completers and non-completers mirrored very closely the conclusions of Amabile and Kramer4: the main difference between the experiences of students that completed the dissertation was their “progressing serenely in a project that makes sense”. Let’s unpack that sentence:

- A project that makes sense: Basically, students that finished the thesis were able to find a PhD direction, a project that made sense to them, and which they really considered their own (maybe not from the beginning, but at some point this “making sense” and ownership developed, or was somehow found). This is in contrast with doctoral dropouts, that described long periods of not having a PhD project at all, aimlessly changing its direction, and/or the direction not making sense to them (e.g., if the advisor had imposed a direction that the student did not understand or agree was important).

- Serenely: This simply means that the doctoral students did not experience too much (emotional) distress from working in the thesis. Even if all of them (completers and non-completers) describe times of struggle, in completers this distress was moderate, or did not appear all the time. People that dropped out often described feeling the PhD as a burden at all times, to the point that any task related to the PhD generated such distress.

- Progressing: PhD students that completed the dissertation described, in their good days, some sort of advancement in the preparation of the materials for the thesis (e.g., a journal article, a chapter of the dissertation itself, gathering data for a study, etc.). Of course, they did not necessarily experience this kind of progress every day of their PhD, but probably they did so frequently enough to keep themselves motivated. Conversely, students that dropped out of the doctorate reported long periods of “being stuck”, “going in circles”, and other forms of stagnation or even going backwards. It is also noteworthy that students seemed to evaluate progress quite frequently, expecting to see some kind of progress almost on a daily basis.

This last point (the frequency in which doctoral students expect to see progress) is especially important. If we think for a moment about the classic indicators of progress in a PhD (getting a paper published, finishing a study or a thesis chapter), and how often they appear (once every… several months?), we can easily see why many doctoral students can feel uncertain about their progress, if they ask themselves about it every day.

That is a lot of uncertainty, for a lot of time. No wonder some just give up.

A small bit of evidence from the field

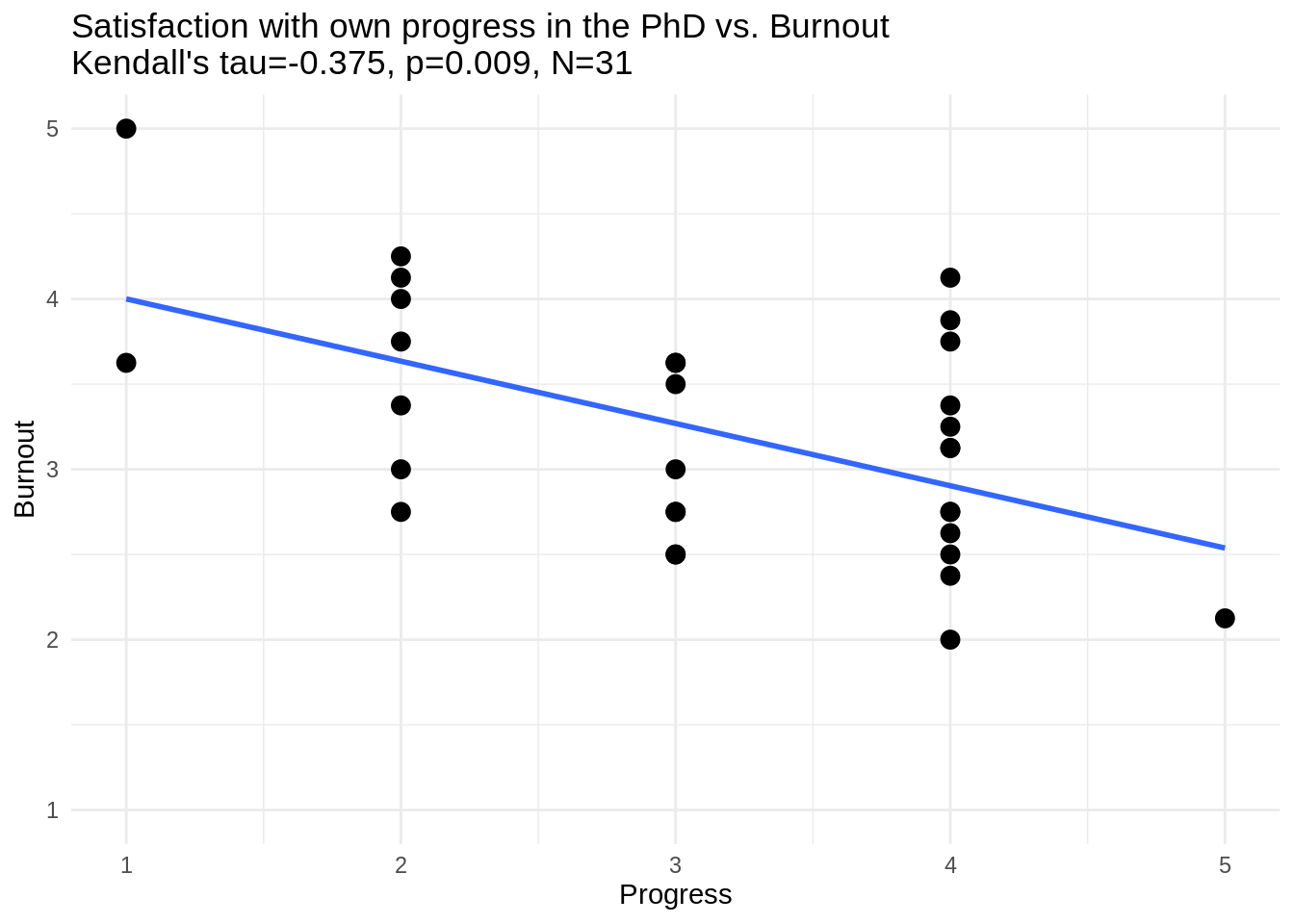

As we can see from the previous two pieces of research, there seems to be some evidence for a close relationship between our sense of progress in work that is meaningful to us, and our work engagement and morale. To test a bit this hypothesis in the context in which I work, we recently ran two workshops about progress in doctoral studies (one in Tallinn University, Estonia, and another in University of Valladolid, Spain). During the onboarding process for the workshops, we asked 31 local doctoral students about how satisfied they were with their progress towards the dissertation. We also asked them several questions from a validated questionnaire to measure their burnout (in terms of stress, exhaustion and cynicism5). The graph below shows the clear (negative) correlation between burnout and being satisfied with one’s progress. Students that reported low satisfaction with their progress also were more likely to report having considered abandoning their doctoral studies. These two pieces of evidence from an international, albeit admittedly limited, convenience sample, also seem to support the same ideas from the studies above: perceiving that you don’t make progress can lead to demotivation and, eventually, dropping out of the PhD6.

Negative correlation between burnout and one's own perception of progress in the PhD, from a convenience sample of 31 PhD students in Estonia and Spain

Cultivate your own progress loop

The more I think about it, the more obvious this connection between progress and persistence becomes. However, one might be tempted to think that there is very little you can really do about it. You either make progress or not, right? Well, as with many psychological phenomena, the answer is yes… and no. You cannot artificially manufacture progress for yourself without actually doing the (often difficult) research work that may lead to progress; what you can do is make it easier to perceive the progress that is already there, and which often goes unnoticed. Here are some practices that could help you with that:

- Make (and celebrate) minor milestones: This is the easiest one, which any of us can implement. Simply, make the granularity of your tasks (e.g., as you put them in the to-do list) small enough that you will perceive progress (i.e., you completed something) a few times a day7. If you put “publish my journal paper” as a to-do list item, you probably will not see progress in your to-do list for years; if you put “write a first draft of the introduction section” (or even an outline of it), you will probably be able to see some progress today. Of course, do not overdo it! Maybe “write a first sentence in the introduction” is not meaningful enough to give you any sense of accomplishment when you tick it off (and, at that level, you will spend more time fiddling with the to-dos than actually working!). Finally, don’t forget to celebrate your accomplishments: if you spent 25 minutes finishing some task towards your thesis, probably it’s OK to take 5 minutes off, stretch a bit, maybe put yourself a cup of your favorite tea, or just revel in the thought that you have laid one more brick towards the edifice of one of your major life goals. Otherwise, if you always just rush towards the next grueling task, you will never get the positive emotion of accomplishment that helps you be more creative and productive in the following tasks (remember the “progress loop” I mentioned above?).

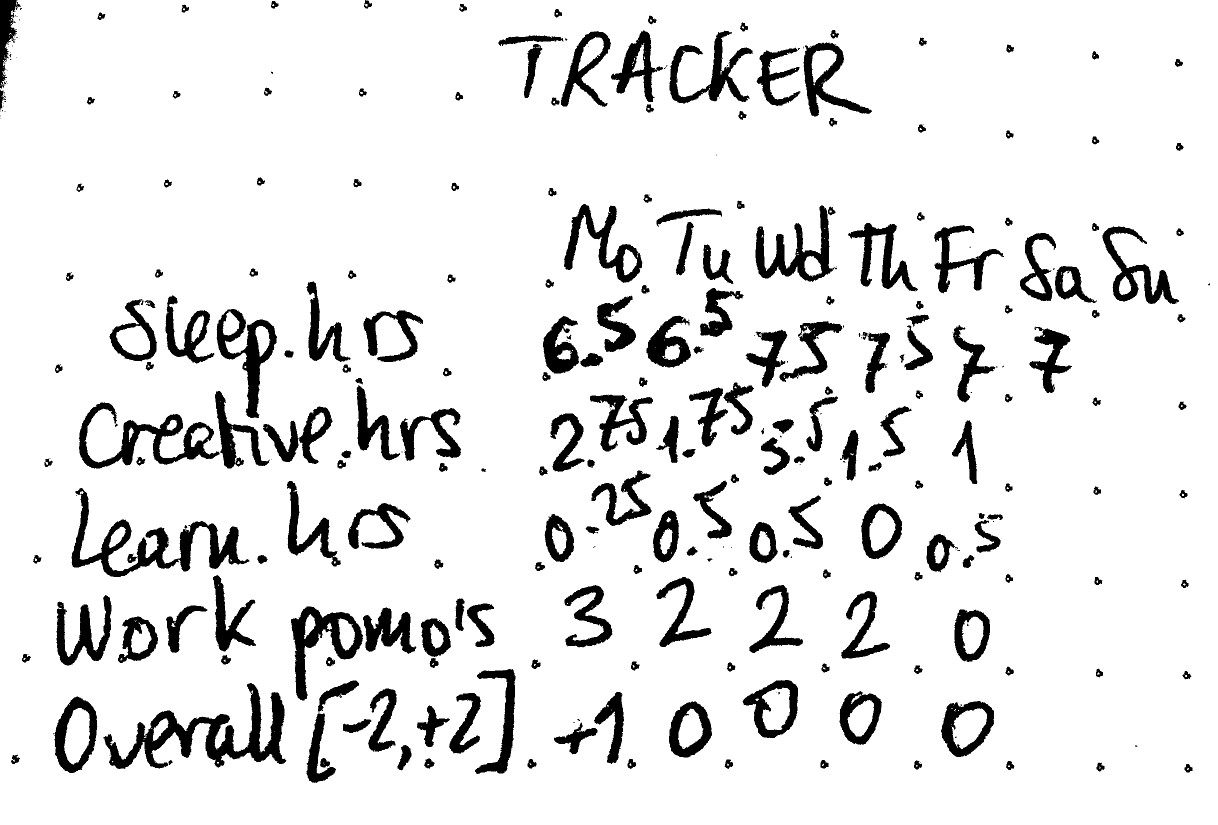

- Self-tracking simple quantitative indicators of progress every day (or every week). One of the main insights of the research works I cited above, and other work in the field of supporting behavior change (i.e., doing more of what you want to do, vs. what we often drift into doing), is that making the desired behavior (or progress) visible helps. One way is just the good old to-do list, as per the point above. However, if there are specific aspects or habits you want to focus on (e.g., writing your dissertation manuscript), you could track explicitly how many times (or how much time) you did that particular behavior today (e.g., note down the number of hours you spent today writing your manuscript). You can create a table (see image below) in your journal, and fill it every day (typically, during your daily review)8. Then, periodically, you can review these tables and see how you are doing (and explicitly notice that you actually have been doing quite a bit of, e.g., writing, towards an important goal of yours). You can also use digital means like a spreadsheet to track these indicators, which enable doing graphs and other neat stuff with it. Indeed, we are starting to investigate technologies and practices to effectively support this kind of self-tracking for doctoral students, at my research group. Stay tuned for more about that!

- Google’s way: OKRs. If you want to go a step further and clearly connect your daily activities (e.g., write X hours every day) with higher-level goals of yours (e.g., finish three great thesis chapters this semester), you can also use a methodology for goal setting called “Objectives and Key Results”9. OKRs have been used by companies and individuals all over (from Google to U2’s Bono) to set and accomplish ambitious goals. I will not go into deep detail here (check the footnote above for more material), but the basic idea is this: you define an ambitious, inspiring objective (O) that you want to accomplish in this period (e.g., the three great thesis chapters mentioned above). This objective can be still a bit vague, but needs to be inspiring, something you put in a sign on your desk, something that makes you jump out of bed in the morning. Then, you define a 1-3 key results (KRs) that encapsulate how you plan to accomplish that, and how will you know that you have reached the objective. It is best if you look at the objective from multiple perspectives to define the KRs (e.g., I plan to write every day, I want to deliver things regularly to my supervisor for feedback, and I need to polish the text iteratively to get it to a good level of quality). The twist is that these key results have to be clearly measurable and time-bound. Thus, in the example above, the key results could be something like: 1) draft text for two hours every workday; 2) deliver a new draft piece every two weeks, for feedback; and 3) iterate every chapter three times with the supervisor feedback. Then, every week you can check back with your OKRs and see how far you have gone towards the inspiring objective, and whether you need to adjust something (be it your environment, your routines, or how you are working), in case progress in the KRs is not advancing at the expected speed.

- Journaling. One interesting thing that happened at the end of Amabile’s diary study was that the participant workers thanked the researchers for letting them do all the hard work of keeping a diary (and answering a ton of questionnaires!). They said that keeping the diary had helped them understand their own work much better: what worked for them, what didn’t, what things motivated (and de-motivated) them, etc. Indeed, taking a few moments each day to write down in a journal has long been reported as having beneficial, therapeutic effects10. There is indeed a long tradition in this direction in many fields of research: the lab notebook, where the researcher writes down the daily advances in the research, new conceptualizations of results, hypotheses, theories, etc. What should you write in your journal? It is a bit up to you. In Amabile’s study, the prompt was simply to write about one particular event from work that day, that came to mind. During my thesis, I often wrote about what new things I had learned about my research that day. I’d maybe have both: write something directly about the research work/content, and something about how was your progress and how you felt today about it. It is also worth noting that much of the learning that comes from journaling happens only when you review the daily entries at a later time (e.g., in your weekly review), and start noticing patterns. Don’t just write your journal, learn from it!

One note of advice about all these practices: keep them simple, brief, don’t overdo them (maybe track 4-5 behaviors every day, tops; keep the journal just a few lines/paragraphs, prompted by 1-2 questions, etc.), as there is the danger of spending more time fiddling with the tracking/journaling than actually working (or dropping it altogether, if it takes too much time). Let’s be clear: do not fool yourself into thinking that these practices will magically make the struggles of the thesis go away. They can help you advance, overcome the struggles, even enjoy them… but the hard work of research still needs to be there.

That said… Give them a try for yourself. See what works for you.

Back to my own days of block, stagnation and lack of motivation after a failed research project… slowly, I realized and accepted that such failures are a normal part of research life (albeit often invisible, as they seldom get published). These feelings of having made mistakes, of being a failure, are not the reality (an action can be a failure, but a person cannot). Rather, the feelings are rather a signal that something did not go well, that there is something to be learned here. Once I realized that something was not going well, the key was to take some action, changing what I did, how I did it, setting goals and plans in a more realistic and productive way. Having a diary and tracking my progress helped me make sense of the process.

What about you? Do you have any tricks or practices to make your own progress visible, or to help others see their progress? Let us know in the comments below!

NB: this post is based on the materials for a new series of participatory workshops that we are running at Talinn University (Estonia) and University of Valladolid (Spain). If you (or someone at your university) think that these ideas could be beneficial for your fellow doctoral students, feel free to drop me a line, as we are thinking about how, where and when to expand this emerging program, once we validate its effectiveness.

-

Amabile, T., & Kramer, S. (2011). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work. Harvard Business Press. ↩︎

-

Amabile, T., & Kramer, S. (2011). The power of small wins. Harvard Business Review, 89(5), 70–80. ↩︎

-

Devos, C., Boudrenghien, G., Van der Linden, N., Azzi, A., Frenay, M., Galand, B., & Klein, O. (2017). Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: A matter of sense, progress and distress. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(1), 61–77. ↩︎

-

Interestingly, the authors of this study do not mention Amabile & Kramer’s work. Seemingly, two different teams of researchers came to very similar conclusions independently in quite different settings, which lend this idea even more credibility, in my mind. ↩︎

-

Cornér, S., Löfström, E., Pyhältö, K., & others. (2017). The relationship between doctoral students’ perceptions of supervision and burnout. International Journal of Doctoral Studies. ↩︎

-

Please note that these data from our workshops (and Devos’s study results) are just correlations which, as you know is not the same as causation (i.e., we don’t know if the lack of progress is making people burn out, or it is the burnout that prevents people from perceiving progress, or there is another factor causing both burnout and lack of perceived progress). The implication that lack of progress can lead to demotivation (i.e., more of a causal link) comes from Amabile’s work, which included temporal analyses in which progress (or lack thereof) preceded temporally work engagement, emotions and productivity (as something happening before another thing is one of the markers of the first thing causing the second). Still, even Amabile’s work just provides hints to that causality, rather than ironclad proof. ↩︎

-

I chose the frequency of “a few times a day” purposefully: In Davos et al.’s study, they note that doctoral students were evaluating their progress (“have I accomplished something…") almost on a daily basis (”… today?"). For what it’s worth, I often tick between 3-6 tasks off my to-do list on a normal day. It can be more on a long, stressful, overworking day (but I normally cannot sustain this rhythm for long). ↩︎

-

Not all behaviors need to be directly related with productive research outcomes (e.g., writing): for myself, I also track things like how many hours I sleep. These behaviors (e.g., sleep, exercise, spending time with loved ones) are not productive per se, but they can also be helpful in keeping your work rhythm (and your progress) sustainable. ↩︎

-

Doerr, J. (2018). Measure what matters: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation rock the world with OKRs. Penguin. Available online here. ↩︎

-

Hiemstra, R., & others. (2001). Uses and benefits of journal writing. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001(90), 19. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.