POSTS

Reviewing doctoral well-being research (study report)

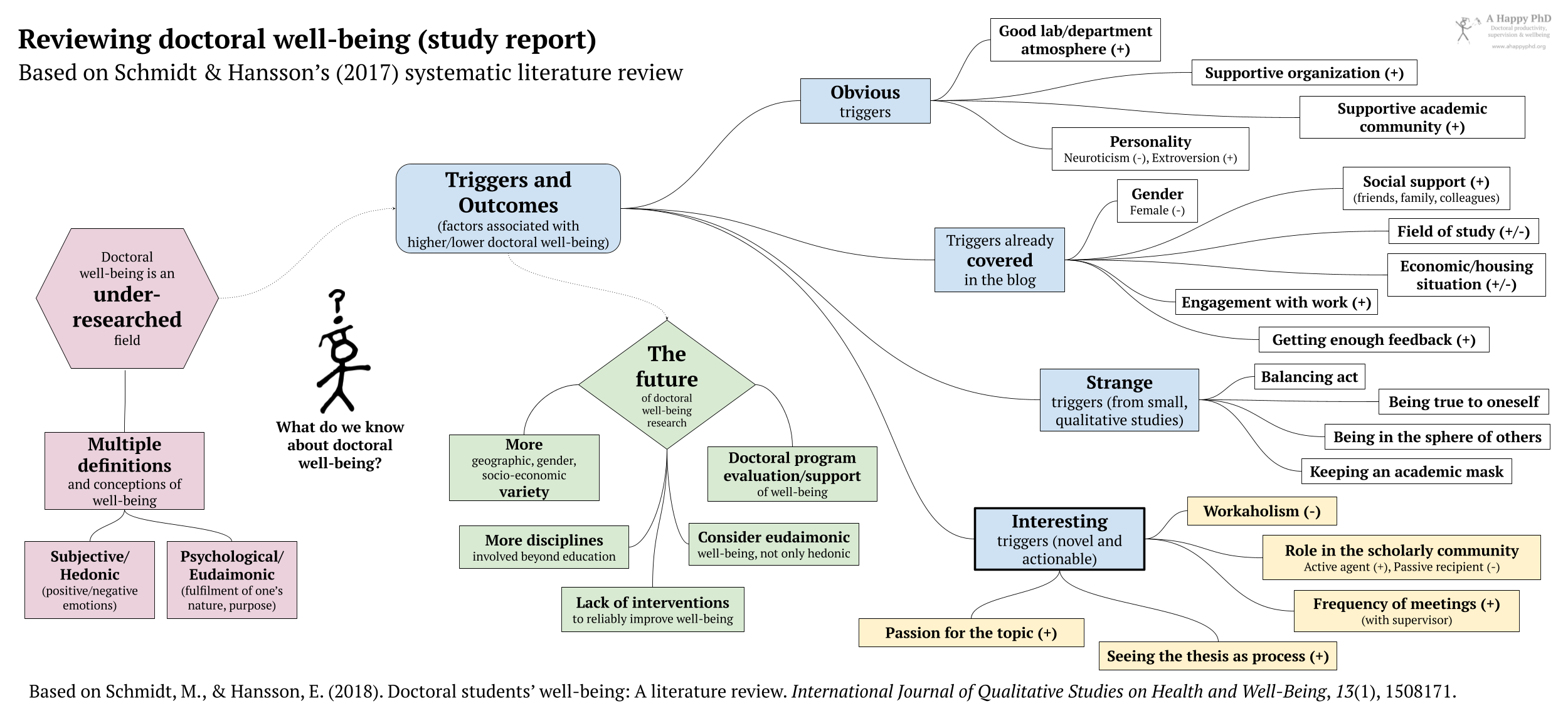

by Luis P. Prieto, - 11 minutes read - 2161 wordsDoctoral well-being is one of the central topics in this blog (indeed, it was the one that started it all, more than three years ago). While I have tried to base my writings in the peer-reviewed research of this area, so far my reading of it has been rather unsystematic. How do doctoral well-being researchers summarize this body of knowledge? In this post, I distill from the findings of a systematic literature review on doctoral well-being, teasing out topics and factors that we already knew about from previous posts as well as novel ones that we can try to act upon.

An under-researched field

One of the aspects I found most striking about Schmidt and Hansson’s (2017) review1 was how small the dataset was: only 17 articles fulfilled the criteria set by the reviewers (which seemed logical and not overly restrictive). This points to the fact that, despite increasing attention by the general media and universities themselves, comparatively few studies have delved into what factors are associated with doctoral student (lack of) wellbeing. Even fewer have empirically tested how to improve this state of affairs (more on this later).

The idea that this is a nascent field of research is also supported by the heterogeneity of conceptions of well-being in the reviewed studies, and the very different theoretical frameworks they ascribe to: there is still little consensus on what well-being is and what are the most useful concepts to study it. There seem to exist two broad conceptions of well-being: psychological/eudaimonic (which relates to the realization of a person’s true nature and potential) and subjective/hedonic (which has more to do with having positive emotions, pleasure and joy). This is similar to what we saw in our post on what is happiness.

Regarding definitions and components: to make a long academic discussion very short, the authors seem to like Medin and Alexanderson’s definition, stating that well-being is “the individual’s experience of his or her health”. A bit more enlightening is their support of Ryff’s six-part model of well-being2, which decomposes well-being into: 1) positive relationships with others; 2) personal growth; 3) environmental mastery; 4) autonomy; 5) purpose in life; and 6) self-acceptance. As we can see from the links, we have touched upon the importance of all those aspects in prior posts. Yet, assessing them systematically once in a while (e.g., when we do our yearly review) and defining how we are going to improve upon each of these areas, would probably be helpful to sustain our well-being.

Triggers and Outcomes

However interesting these definitions and aspects of well-being are, maybe the most interesting part of the Schmidt and Hansson’s review is in Table IV (p.9), which lists what authors call the “triggers and outcomes” of well-being. In other words, the factors that the reviewed articles had related to higher/lower well-being of doctoral students (be them from N=2 or N=1600+ studies). I have classified these factors in four broad groups:

- The obvious ones: There are aspects investigated in the literature that have rather intuitive relationships with doctoral well-being. For instance, having a good lab/department atmosphere or being in an organization that is supportive of the doctoral students, has been linked with higher well-being (and is part of our considerations for whether and where to do a PhD). Similarly, being embedded in a supportive academic community (be it locally in your university, or internationally in the form of research associations and similar entities) also seems beneficial. The studies also found links between well-being and one’s own personality traits, which are coherent with trends in the general population: people trending towards neuroticism tend to have lower well-being (in terms of negative emotions), while more extroverted people tend to have more positive emotions and satisfaction with life. The main problem of all these factors is, of course, that there is not much we can do to affect them as individuals.

- The covered ones: There is another set of factors uncovered in the review which we had already covered in our exploration of correlates of mental health issues. Sociodemographic factors like gender (female students tend to have lower well-being), social support, field of study or economic/housing situation, all seem related with doctoral well-being. Not surprisingly, the student’s level of engagement with their work is also related with their well-being (higher is better). The role of the supervisor has not been neglected by these studies either, which found that getting enough feedback is also correlated with lower student stress, anxiety and exhaustion.

- The strange ones: The studies in the review also uncovered several factors (or, should we call them “themes”?) related to wellbeing which I don’t know what to make of. These themes seem to come from small-scale qualitative studies, so they seem to be more related to particular students’ stories and sense-making, rather than attempts at generalizable factors. Doctoral well-being is in some studies characterized as a “balancing act”, between multiple obligations (jobs, the thesis, family…), or between being true to oneself and being “in the sphere of others” (be them the scholarly community, or our own family). Keeping an “academic mask” was identified as a strategy for coping with the stresses of the PhD, but it is unclear whether it is a healthy one, since it is also connected to feelings of incompleteness and exhaustion.

- The interesting ones: We have a final category of factors related to well-being, which seemed more interesting, as they were either unknown to me, or more directly under the control of individual doctoral students. For instance:

- Workaholism (which is such a common strategy in academia that one could consider it adaptive) was related to lower job satisfaction, higher stress and sleep problems – which is not surprising once we consider that it is, in the end, an addiction like any other.

- Our role in the scholarly community, in particular whether we are active agents in it (think, reviewing papers for venues in our area, or participating in conferences and other scholarly events), has been related with higher well-being (in terms of anxiety, exhaustion, etc.). Although this might seem counterintuitive (how is doing more things on top of your dissertation decreasing exhaustion?), it actually makes sense from a self-determination theory perspective, since acting in such communities can foster our feelings of connection, mastery and autonomy. Conversely, being the passive recipient of the community (just receiving negative feedback, doing other thankless chores within it) or feeling a lack of equality/empowerment within our academic community, is connected to lower well-being.

- A passion for our research topic has also been linked to increased well-being and academic satisfaction. This could be related both with our sense of autonomy (again, self-determination theory) and with our sense of purpose, which are known to be important for our happiness. This is also why we recommend doctoral students to do “thesis topic sense-making” exercises like the CQOCE diagram.

- Doctoral well-being studies have also found that seeing the thesis as process (in contrast to seeing it as a product) is also related to higher well-being. In other words, understanding that the dissertation is a learning process, a practice that lets us develop important scientific skills (not just “a book I have to write and be done with”) will help us better cope with potential setbacks and errors, since those are an integral part of any learning process. This realization is behind our recommendation to make this process view explicit, with exercises like the “map of the thesis”.

- The frequency of meetings (with the doctoral supervisor, assumedly) is a very simple and relatively easy to control factor for increased well-being (and satisfaction with the supervision). Of course, this finding should not lead us to “meet just for meeting’s sake”: we should find ways to make meetings more effective and efficient, so that doing them frequently is feasible and useful for everyone involved.

The future of doctoral well-being research

As noted above, doctoral well-being seems to be a comparatively young research field, with many unexplored areas and a lack of consensus even on basic questions like what is well-being. The authors of the review performed a Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats (SWOT) analysis of the literature they had found, which may help us understand where this research should go next, and what kind of questions we still don’t have answers to, in relation to doctoral well-being:

- Geographic, gender, socio-economic variety: most of the studies reviewed were done in the US, Canada, and other WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic)3 countries. This of course means that we know very little about the situation in other countries, and whether the same findings and factors will also hold there or not. The same goes for doing studies that focus on a wider variety of gender and socio-economic factors, which are still largely unexplored.

- Disciplines beyond education: Most of the studies in this area come from the discipline of education (which is natural). Yet, inter- and multi-disciplinary efforts involving scholars from psychology, management, or even technology4, could help in providing new insights (and solutions!) to the endemic problem of low well-being in doctoral education.

- Doctoral program evaluation and support for well-being (not just for academic success or thesis completion) is another area that could be improved in most institutions around the world, where there is an increasing (but still marginal) acknowledgement of these issues. This kind of institutional and systemic change could make a big impact in many of the institutional/community factors we noted above, on which individual students themselves have comparatively little agency.

- Beyond hedonic well-being, into eudaimonia: The review authors noted that most of the works in this body of research represent well-being from a hedonic perspective (basically, positive/negative emotions), probably because it is easier to measure. More studies that complement this perspective with the eudaimonic one (focusing on our sense of purpose and meaning, as some modern psychotherapies do) would give us a more complete view of doctoral students’ well-being.

- Lack of interventions: although the review authors note as a strength that the research analyzed tried to apply their findings to doctoral education practice, the fact is that these applications often are “general recommendations” and it is unclear how one should intervene to change the current state of affairs (or whether it works to do it). Similar reviews in the area have noted this lack of evidence-backed interventions to improve doctoral well-being5,6. In this sense, the authors of the review suggest to focus on social and problem-focused coping strategies (which is a bit what our doctoral student workshops try to do7).

So, drawing from the ideas above, make sure to not engage in workaholic behavior, be an active agent in your scholarly community, understand and be passionate about your topic and the learning process you’re going through, and meet frequently with your supervisor. Otherwise, finding a doctoral program that actually cares for well-being (or prompting your current one to do so) would also help.

I hope you found this quick tour of doctoral well-being research as interesting as I did (at least, it showed that many of our previous writing on the topic was not too far off-base). The main ideas of this review summary are represented graphically below. Feel free to share it with your colleagues, supervisors (or students). Spread the word!

May all your being be well, indeed :)

Did you find this review of doctoral well-being useful? what did you miss? should we do more of these in-depth paper summaries, or stick to the classic posts? Let us know in the comments section (or leave a voice message) below!

Header image by DALL-E.

-

Schmidt, M., & Hansson, E. (2018). Doctoral students’ well-being: A literature review. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 1508171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1508171 ↩︎

-

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 ↩︎

-

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. ↩︎

-

Prieto, L. P., Rodríguez-Triana, M. J., Odriozola-González, P., & Dimitriadis, Y. (2022). Single-Case Learning Analytics to Support Social-Emotional Learning: The Case of Doctoral Education. In Y. “Elle” Wang, S. Joksimović, M. O. Z. San Pedro, J. D. Way, & J. Whitmer (Eds.), Social and Emotional Learning and Complex Skills Assessment (pp. 251–278). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06333-6_12. ↩︎

-

Mackie, S. A., & Bates, G. W. (2019). Contribution of the doctoral education environment to PhD candidates’ mental health problems: A scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(3), 565–578. ↩︎

-

Jackman, P. C., Jacobs, L., Hawkins, R. M., & Sisson, K. (2022). Mental health and psychological wellbeing in the early stages of doctoral study: A systematic review. European Journal of Higher Education, 12(3), 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2021.1939752 ↩︎

-

Prieto, L. P., Odriozola-González, P., Jesús Rodríguez-Triana, M., Dimitriadis, Y., & Ley, T. (2022). Progress-Oriented Workshops for Doctoral Well-being: Evidence From a Two-Country Design-Based Research. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 17, 039–066. https://doi.org/10.28945/4898. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.