POSTS

Facing addiction to social media in the PhD

by Luis P. Prieto, - 22 minutes read - 4591 wordsAre you spending more time on social media than you would like? Is your use of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok… hampering progress on your doctoral research? You are not alone: many doctoral students report in our workshops that spending too much time scrolling compulsively on social media is one of their biggest productivity challenges. Building upon the insights about dopamine and addiction from our previous post, here I go over eight concrete steps we can take to break this compulsion and do more of the things we think are really important (like finishing that thesis).

Oddly enough, I started using social media because of my PhD. Back in 2009, Facebook was the easiest way to stay in touch with other PhD students you met in an informal way, without exchanging email addresses. Facebook was novel, convenient and non-threatening…

Fast forward to 2022, Facebook has probably reached saturation (i.e., everybody that would be there is already there), and other social media platforms (e.g., Tiktok, Instagram) starting to eat up its user base. It is difficult to find someone that does not have any social media account, and Facebook (or its competitors) is the main news and entertainment source for many people, under the promise that its algorithms customize “the Feed” to suit what is interesting and engaging for each of us. And it seems to do that successfully, as people spend on average more than two hours a day using social media (147 minutes, to be precise!).

Yet, these technological marvels do not come without problems – especially, if you are a doctoral student. Social media (sometimes expressed more widely as “the smartphone”) is mentioned in almost every doctoral workshop we run, when talking about candidates’ productivity challenges. Social media seems to provide frictionless, momentary relief from the difficult emotions that a PhD often brings about (boredom, uncertainty, low self-esteem, impostor syndrome…).

Of course, we are more aware now of the costs and potential dangers of social media: the correlations between social media use and depression have been widely reported1; popular documentaries like The Social Dilemma provide compelling arguments not only about the effects of social media on our mental health, but also on political polarization, misinformation, etc. Other people have argued that we should quit social media altogether (especially, if we care about our intellectual output).

The jury may still be out on the issue of whether social media use causes by itself depression2, although recent studies provide stronger evidence of causality3. But, we will not argue here whether it makes sense to stop using social media on that (probably still valid) large-scale epidemiological (or even experimental3) basis. Rather, I’d like us to take a very personal, individual criterion for such a decision, based on the definition of addiction we saw in the previous post. Take a minute and reflect:

- Am I using social media for longer than I would like?

- Am I in control of when and how much I use social media (vs. it being a compulsion)?

- Would I (or others) benefit from my using social media less?

These questions could be summarized into what behavior designer Nir Eyal calls the “regret test”: do we, after doing a behavior, regret having done it (or done it for so much time)? If the answer to any of these questions is “yes”, then we may have a problem. We are not spending our time in an intentional way. If, as PhD students, we are spending those 147 minutes a day on social media, we may consider how much more our research could progress if we spent that time actually doing research activities (or sleeping, meditating, or exercising)!

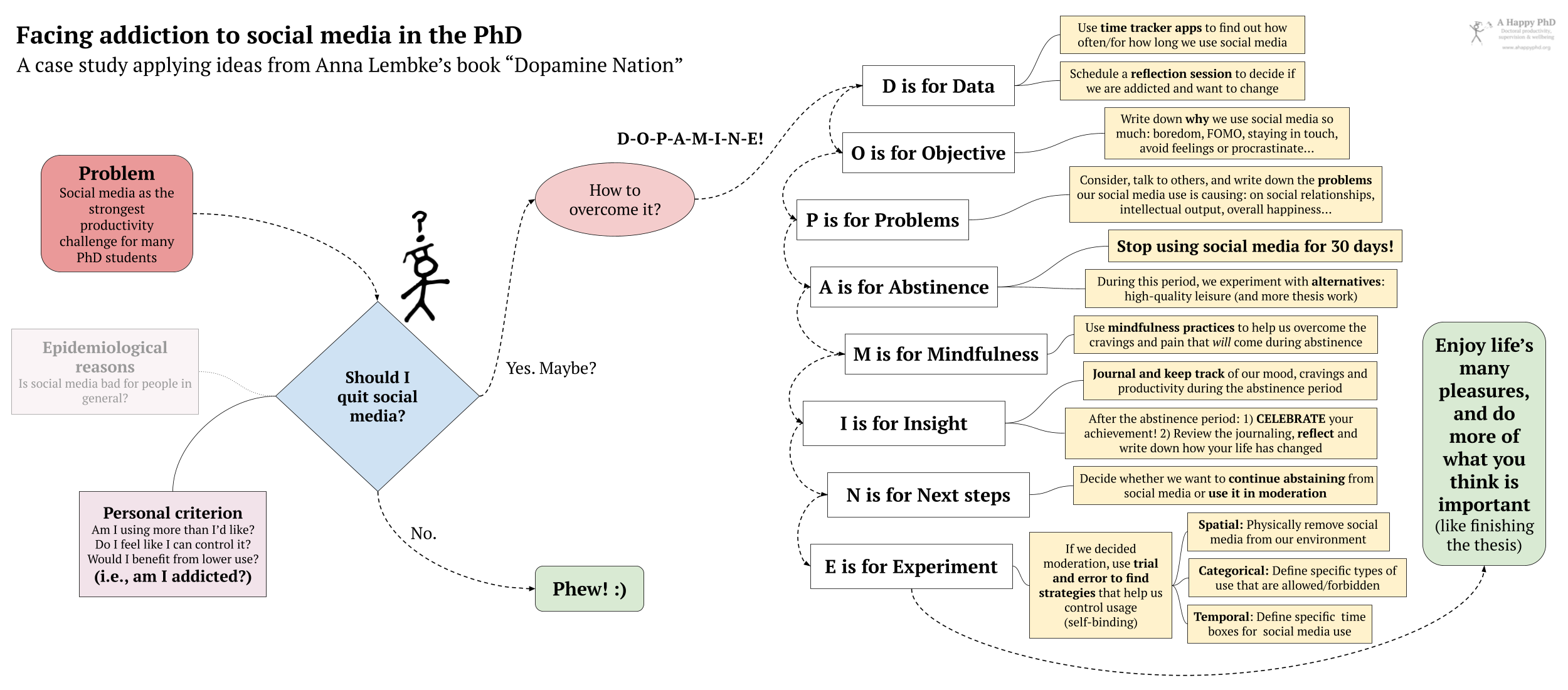

So, what can we do if we realize our social media use is problematic and we want to stop this “addiction”? Below is a sequence of eight steps we should take, according to expert in addictions Dr. Anna Lembke4.

Step 1: Gather Data about our social media consumption

The first step is to understand whether we really have a social media overconsumption problem, and how bad it is (maybe we are just over-worrying??). To do that objectively, we could track for about two weeks how much time we spend on our social media channels and how many times we access them…

… The problem is that our social media use is highly fragmented (especially if we have access to it in our phones, just one tap away at all times): two minutes here while we wait at the supermarket queue, ten minutes there between actual thesis work pomodoros, an indeterminate amount of time when we go to bed and we scroll and scroll to “catch up” on what happened today in our world… We could note this down in our trusty paper journal every time we access social media, but remembering to do it (and having the journal on us at all times) can be difficut. A more reliable way to do this tracking in the “time confetti”5 of modern life is to use time tracking apps such as RescueTime , Harvest, or StayFree. If our social media consumption is more centralized (e.g., we only use it from our smartphone), there are easier options to track such time: Facebook and Instagram’s own app have a simple report in their own settings, and both Apple and Android have “screen time” or “digital wellbeing” tools that give similar information.

After this tracking we should schedule a small session (half an hour maybe), to look at the data and reflect: How much time do I spend on social media? How many times a day do I access it? Am I satisfied after spendind such time? Do I think that this time could be better spent elsewhere? If the answer to the last question is “yes”, proceed to Step #2.

Step 2: What’s our Objective when we use social media?

In the reflection session mentioned above, with our consumption data at hand, we can also ask ourselves why we spend so much time on social media. Brainstorm a list of reasons, but make them more concrete than “I like it” – keep asking “why?". If we run out of ideas, we can look again at our consumption data: which days is consumption higher, and what happened those days? what times in the day do we use social media, and what seems to trigger the use?

The idea here is to uncover what is our personal logic for social media consumption. Typical responses could be one or more variations on the following:

- Social media is the modern “cure” for boredom. Whenever we are bored or don’t know what to do, endless entertainment is just one tap away in our social media feed.

- Related to the previous one, social media could be our primary way to stay up to date on the latest news (in the world or locally, among our friends and acquaintances).

- We could also use social media to actively stay in touch with family and friends (this is very common since many PhD students emigrate to other countries to do their doctorate). We can note here what kind of “social activity” we tend to do more often there: audio/videocalls? text messages? single-tap likes or retweets?

- Finally, social media could also be a strategy to avoid very common difficult emotions, thoughts or situations (e.g., about our writing skills about our chances to finish the PhD, our progress, difficult social situations, or other personal problems), or simply to procrastinate on tasks that we dislike or are afraid to do (especially, related to our doctoral research) .

Don’t judge yourself or the goodness of these reasons. These are just the reasons your brain (which, as any human brain, is not always fully logical6) has come up with to use social media, in your particular context of day-to-day life.

Step 3: What Problems is social media causing in my life?

Once we have considered the benefits (real or imagined) of using social media so much, it is time to look at the costs, the problems it may be causing as well. A few typical themes we can reflect on include:

- Is the quality of our social relationships better or worse since we use social media a lot? Please note that this is about the quality of our friendships (i.e., do we really feel connected, compassionate towards other people, and happy to communicate with them?) rather than its quantity (e.g., having 600+ Facebook friends or Twitter followers).

- Do we generally feel happier and more engaged with life, now that we have this marvelous machine that helps us avoid boredom, insecurity, and many other uncomfortable thoughts and emotions? Or just the opposite?

- Is our intellectual output better or worse than it used to be before we used social media so much? Especially if we are doctoral students doing cognitively demanding work, some authors suggest that glances into social media while we work make our brains “switch context” away from the task we’re doing, and can have a hidden cost due to “attention residue” (i.e., our brains keep thinking about what we saw in social media for a while, even after we purportedly return to our task)7.

- Have we become more entrenched in our political views or other kinds of opinions? Do we hate other people more, or think they are hopelessly stupid or evil? The way social media algorithms feed us with news and other content that align with our views may be contributing to polarize our views, in what researchers have called “echo chambers” or “filter bubbles”8.

- Look at the opportunity cost of your social media usage: now that you know exactly how many hours a week you spend on social media (see Step #1) – is social media the best use of that time? Look at what is really important for you, in your life (chances are that your dissertation is somewhere in there!). If you magically found that much additional time in your days, would it help you advance noticeably towards those important goals?

It is worth noting, as we did in the last post, that seeing these problems clearly requires an unusual degree of self-awareness. If we are addicted, we may be blind to these problems, or we might disregard them as minimal. Thus, we probably should contrast our own reflections and assessment of the problems above with other people that know us well (maybe, people who knew us before we started using social media so much). Ask them: are our relationships better now? do we seem happier? do we seem more focused, more smart? have we become politically polarized? You may be surprised.

Once we have a list of concrete problems social media is causing in our lives, the big question comes: do these problems outweigh the benefits (Step #2)? Do we want to stop (or moderate substantially) our social media consumption? If the answer is yes, head to Step #4 below.

Step 4: Go through a month of Abstinence

This step is simple (but not easy): just stop using social media for 30 days. Typical steps to achieve this include:

- Uninstall all social media apps from your phone, to create additional friction in case you give in to temptation.

- Use social media blocker apps such as Offtime or this Chrome add-on, to prevent yourself from accessing your social media.

- Change your social media accounts’ passwords to something very difficult, write it down (don’t memorize it!) and give it to someone you trust, under the promise to give it back to you once the abstinence period ends.

NB: This step is similar to what some people call a “Digital detox”, or what author/professor Cal Newport calls “Digital declutter”9. This is, however, a wider exercise that covers not only social media but also other uses of smartphones, like email or instant messaging. If you feel that your addiction is wider, you could also try these steps from the beginning, but with such wider focus.

We will face pushback when we try this. People we communicate with frequently through social media and people that use social media a lot may feel judged by our stepping away from it (but we can still communicate with them through other means, e.g., phone calls). We could announce this abstinence explicitly and publicly to others, but it is a good idea to phrase this month of abstinence as an experiment to test yourself, not as a moral judgement on others. That said, if we have friends, labmates or family who share the same addiction to social media (and who are equally motivated to quit it), we could also ask them to join, in a sort of “group challenge” (the “prosocial shame”4 will help all members of the group to “stay clean”).

Taking a page from Cal Newport’s digital declutter process, I think it is quite important during this abstinence period to experiment with and add back to our lives alternative positive stimuli. Write down a list of “analog” leisure activities that are of higher quality, especially activities you used to enjoy, be it long walks and conversations with friends or cooking and hosting (phone-free?) dinners with family members. Also, consider experimenting with activities that require sustained attention and mindfulness, which you think you could enjoy: playing a musical instrument, taking up photography again, etc. Every time we feel the urge to come back to social media, we can take a look at our list, and maybe do one of those other activities instead (unless the urge is an “uncomfortable thought/emotion trigger”, see Step #5). You could even try to slowly add back some thesis-related work, in the time you used to dedicate to social media (don’t do it just before bed, though).

Step 5: During the abstinence, train your Mindfulness

The 30-day abstinence period will be hard, and it will seem at times like an awfully long test of your willpower. This is in part due to dopamine affecting our perception of time4… plus all the craving-induced chatter in our heads trying to convince us to check social media (just for a little moment! it is very important!). One way we can counter these mental self-sabotage is to use mindfulness practices, as research has now found and documented many benefits of mindfulness for the treatment of addictions10, including studies about smartphone addiction (a superset of social media addiction) in university students11.

We can both start a regular mindfulness meditation practice, as well as more informal, in-the-moment mindfulness exercises when we are assaulted by our social media cravings. There are simple mindfulness exercises for addiction recovery. If you managed to convince others to join your “social media abstinence challenge”, you can do many of these mindfulness practices in a group as well. We can also practice using the other mindfulness practices we have mentioned in previous posts, like the exercise to sit with uncomfortable thoughts/emotions as we write a research paper.

Try mindfulness out, I have found it tremendously useful for overcoming my own (social media and otherwise) addictions. Its effects get stronger with practice!

Step 6: Gather your Insights after the month of abstinence

I recommend you to journal daily throughout the 30-day abstinence period (even if we do not write a journal normally). In this “abstinence journal” we can record, at the end of the day (or at any moment, really) how many cravings for social media we have experienced, how it made us feel (i.e., bodily sensations), what kind of arguments the craving mind invents to convince us to break the abstinence… But also how we feel the rest of the time: are we happier? more distracted? do we manage to spend more time working on what we think is important? are we more or less productive than usual? Anything special that we notice, really. We can take inspiration from David Cain’s “life experiment” logs, for instance. If we self-track a few quantitative variables related to your progress and wellbeing, that can also help us notice trends.

Once we have successfully stayed away from social media for 30 days, it is time to 1) celebrate, pat ourselves in the back – what we just achieved is no small feat! and 2) program a reflection (book in your calendar 30-60 minutes of quiet alone time!) to gather our insights. This (preferably written) reflection can be free-form, but we could go over the abstinence journal entries for these 30 days, and use my weekly review question structure. The goal is to have in the end answers to questions like: how has the process been? how do we feel now, after a month of abstaining? what have we learned about social media and our leisure time? do we still think social media is an essential part of our life? Have we discovered higher-quality ways of spending our leisure time? What problems has the abstinence provoked in our life? Have we made better progress in our thesis work lately? Do not expect magical changes from day 1, but maybe some things did change as the month of abstinence went on.

Write down your conclusions, and go to Step #7.

Step 7: Define what are your Next steps regarding social media

Now it’s the moment of truth, where we decide what we will do from now on, informed by evidence and reflection. We can either:

- Continue abstaining from social media: if we discovered during the month of abstinence that social media was not really so useful or necessary in our lives, or that the alternative uses of our time are so much better, then we can just quit social media altogether. We would just delete all our social media accounts, uninstall social media apps from our phone, remove all bookmarks related to it… and continue happily with our lives, free from this addiction-inducing element.

- Keep doing social media, but in moderation: if we discovered that there are aspects (or types of use) of social media that were still beneficial and important for us, we can decide to keep using it, but in a much more controlled manner. See Step #8 for more details and strategies on this.

In either case, we can again use the power of “prosocial shame” (i.e., social enforcement) to help us keep this decision. By telling others (especially, people we trust) what we decided and asking them to help us stick to that decision, we can counter eventual temptations and lapses in our willpower.

Step 8: Experiment with different strategies to keep consumption under control

If we choose to quit social media for good, that’s comparatively easy to implement. But, what if we decide that social media has still some important value in our life (e.g., it is the only way to communicate with certain people we care about)? What if moderation is the way to go?

First off, no judgement from my side: I still have Facebook and Twitter accounts (which I use rather infrequently). Again, this post is not about telling everyone to quit social media – it is about helping you to do what you think will most benefit your life in your particular circumstances.

According to Lembke’s book, the key to success in moderately engaging with dopaminergic behaviors is to experiment with what she calls self-binding strategies12: intentionally creating different kinds of barriers between us and the substance/behavior. In this experimentation we go back to what we learned in steps #1, #2, #3 (about the benefits and problems of using social media, our triggers for uncontrolled usage, etc.) and try to apply that knowledge to our advantage: how can we reap the maximum of benefits without incurring in the costs/problems of using social media? Lembke defines three kinds of self-binding:

- Space/Physical self-binding: This category is about removing the opportunities to consume from our (digital and physical) space. Removing social media apps’ desktop and phone notifications (basically, “reminders to consume”) would probably be a good first step. Uninstalling the apps from our phone (e.g., if most of the unwanted uses happen there) is a probable one as well. We can also use what Cal Newport and others call the “phone foyer method”: creating a rule for ourselves that, when we are home, our phone will live in a fixed place (e.g., the foyer or entrance room) – as opposed to living in our pocket at all times. We can also use social media blocker software, give our (un-memorizable) password away to a trusted friend, swap our social media shortcut/icons so that they point to our meditation app… whatever helps us create friction and put social media out of our way until we really think this is a good moment to use it.

- Time/Chronological self-binding: This is about making sure that we only use social media at certain, very specific times. A classic example would be to use social media as if it were a good-old TV program (remember those?), at fixed times in the week and for a fixed duration. For instance “I will only use social media for 50 minutes on Fridays at 8pm”. We could also say that we will only use social media as an (again, timeboxed) reward after we complete some hard task of our PhD (a variant of “granny’s rule”). This category of strategies often needs to be combined with the physical self-binding strategies above, to ensure we do not fall for the temptation outside of our designated time slots. Also, we can keep the time tracker apps from step #1 active, to check periodically and see if we are complying with our temporal strategy for social media consumption.

- Meaning/Categorical self-binding: Using information about the good things we take out from social media (see step #2), we can define different categories of social media use, some of which are undesirable (e.g., endless, passive doomscrolling for news or “catching up” fosters unhealthy social comparison and correlates with mental health issues13) and some that are OK (e.g., video calling particular friends to know what they are really up to) – and engaging only in the desirable ones. We can use additional strategies to support such intentional use of social media (e.g., use a browser plugin that removes the Facebook news feed, or keeping a monday mantra card on sight, saying “Is this the use you want of your time?").

One last tip about experimentation: this will not work perfectly the first time! It is important to iterate, to try different strategies if the ones we first thought of did not work. We can keep the time trackers running and program in our calendar some time for looking at our social media usage results and reflecting what other strategies we may use, if we were not successful at curbing our consumption. Also, very important: do not try to stop your addiction starting with the experimentation step! (which is a common temptation). The abstinence period (step #4) is really important to re-balance our brain’s dopamine system – otherwise, it will be too easy to fall back into the addiction compulsively, without even noticing.

The diagram below summarises the main ideas covered in this post:

Ah, the irony…

Many of you may be smiling at the irony of this post: you may have found this post by following the blog’s social media channels. Am I not fostering such addictions by using these channels for getting to an audience? On the other hand, should we not “meet people where they are”? (it certainly seems that almost everyone is in one of these social networks). This dilemma, along with reports from some of you that, even if you followed/liked the blog, you don’t manage to notice new posts as they come out in your algorithmically-concocted news feed, has led me to try to slowly move away from the big social networks, by providing an attractive, easy to use alternative: the Happy PhD Newsletter, a brand-new, more professional, and completely free newsletter for the blog14. Don’t worry, we will still be announcing new posts in social media as per-usual for some time… but consider joining the newsletter if you want to get a weekly email alerting you to new blog posts, flashbacks and blog-related announcements, directly in your inbox. Newsletter subscribers will also get access to additional exclusive goodies like the “strategic plan towards your next dissertation milestone” or powerful “tiny practices/ideas”, without being at the mercy of what the social media algorithms think will addict engage them more.

I did not want to close this (already quite long!) post without a last piece of advice: If we decide to quit social media (or moderate our usage), it is best to do it from a positive place of knowing what is important in our lives, what we value, and what are better uses of our leisure time (see step #4). This will help us be eager to do it and see the quitting as a positive, meaningful effort… not one of deprivation.

May you stay free!

Are you addicted to social media? Did you try the steps above to moderate or eliminate that addiction? Did they work? Let us know in the comments section below!

Header image by Pixahive.

-

Lin, L. yi, Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller, E., Colditz, J. B., Hoffman, B. L., Giles, L. M., & Primack, B. A. (2016). ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION AMONG U.S. YOUNG ADULTS: Research Article: Social Media and Depression. Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22466 ↩︎

-

Hartanto, A., Quek, F. Y. X., Tng, G. Y. Q., & Yong, J. C. (2021). Does Social Media Use Increase Depressive Symptoms? A Reverse Causation Perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 641934. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.641934 ↩︎

-

Lambert, J., Barnstable, G., Minter, E., Cooper, J., & McEwan, D. (2022). Taking a one-week break from social media improves well-being, depression, and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. ↩︎

-

Lembke, A. (2021). Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence. Penguin. ↩︎

-

Schulte, B. (2015). Overwhelmed: How to work, love, and play when no one has the time. Macmillan. ↩︎

-

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux New York. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374533557 ↩︎

-

Newport, C. (2016). Deep work: Rules for focused success in a distracted world. Hachette UK. ↩︎

-

Spohr, D. (2017). Fake news and ideological polarization: Filter bubbles and selective exposure on social media. Business Information Review, 34(3), 150–160. ↩︎

-

Newport, C. (2019). Digital minimalism: Choosing a focused life in a noisy world. Penguin. ↩︎

-

Garland, E. L., & Howard, M. O. (2018). Mindfulness-based treatment of addiction: Current state of the field and envisioning the next wave of research. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 13(1), 1–14. ↩︎

-

Lan, Y., Ding, J.-E., Li, W., Li, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, M., & Fu, H. (2018). A pilot study of a group mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for smartphone addiction among university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1171–1176. ↩︎

-

A reference to the episode in the Odyssey where Ulysses wants to hear the singing of the Sirens, and has his men tie him to the mast of their ship. ↩︎

-

Meshi, D., Morawetz, C., & Heekeren, H. R. (2013). Nucleus accumbens response to gains in reputation for the self relative to gains for others predicts social media use. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00439 ↩︎

-

There is also the blog’s RSS feed (see the right-most option of the menu at the top of any page in this blog), but I reckon comparatively few of you use RSS regularly, or would want to start using it only to be up to date about this blog’s new posts. ↩︎

Luis P. Prieto

Luis P. is a Ramón y Cajal research fellow at the University of Valladolid (Spain), investigating learning technologies, especially learning analytics. He is also an avid learner about doctoral education and supervision, and he's the main author at the A Happy PhD blog.